The Magical Wonders of Git

Why git?

git is a simple but highly flexible system for keeping track of stuff on one or more computers. But, everyone probably already has some way of doing the same thing. Why should I spend my time learning git?

NOTE: To access the repository and most up-to-date information for this workshop, head to our github page.

How do you keep track of your changing files and documents?

If you’re like most academics, you’ve probably got some version of this extremely versatile naming convention:

- analysis.R

- analysis_new.R

- better_analysis_new.R

- better_analysis_new_FINAL.R

- better_analysis_new_FINAL_for_real.R

- better_analysis_new_FINAL_for_real_for_real.R

- F*$%^!HF@#KAJVRSAWEOH!#LD.R

- …

If you’re working with a folder with multiple files changing inside, you probably do the same kind of thing: duplicate the folder and make some changes to some files.

Now, this might be all you need if you’ve got a fantastic memory. But have you ever come back to one of these sorts of projects after a month, or a year of not looking at it? If so, you probably know that it’s basically impossible to tell what the differences between the files are, why they’re all different, and which file is really the final version.

Thankfully, some programmers got sick of doing this, and they’ve made a tool to make everyone’s lives just that much easier. It’s called git.

What does git do?

You can think of git as letting you set “save points” for your files, just like you hit save points in video games. Once you hit a save point, you can always go back to that version of your files at any time in the future.

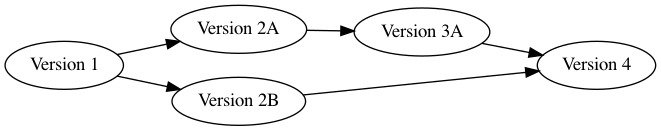

To do this, git will put in a (hidden) folder named .git inside your project folder. This .git folder keeps a list of all of the save points you’ve hit in the past. Specifically, it keeps track of which files change and what changes are made between save points. You’ll end up with something like the graph below of save-points, where every version is made by changing some previous version. So if you start with a version 1, make some changes for version 2A, make some more changes for version 3A, make some different changes to version 1 for version 2B, and merge together version 3A and version 2B into version 4, git will store this graph:

As you can see, this is pretty useful: your older versions are always there for you to look back on, you can “branch” off into different directions from any version, and you can “merge” different branches with different sets of changes back into a final version.

What if I’m working with other people, or on multiple computers?

This is where GitHub comes in. It’s a place where you can put your files online, so that anyone (with access) can download your files, make changes to them, and upload the new version for others.

Terminology

Before we get into the details of using git, let’s set up some standard terminology:

- Repository: the folder that holds all of your files, as well as a

.gitsub-folder - Commit (noun): a “save-point” that freezes on version of your repository

- Commit (verb): to create a new commit local to your computer

- Branch (noun): a sequential chain of commits that has a name (e.g., “master”)

- Branch (verb): to create a new branch

- Clone: to download a repository from the internet (e.g., GitHub) to your computer

- Checkout: to switch to a commit (or, open a save-point)

- Fetch: to update your

.gitfolder with changes made online - Pull: to apply new commits to your old repository- like “Fetch” but also applies new changes

- Push: to update the online repository with your new commits

- Merge: to mix together two sets of changes from two different branches

Setup

Installation

Windows

Mac OSX

- Install HomeBrew

- Open a terminal

- Type in

brew install gitand pressEnter

Linux (Ubuntu)

- Open a terminal

- Type in

sudo apt-get install gitand pressEnter

In this tutorial, we will focus on using git within the terminal (I promise, you’ll get the hang of it!). If you prefer to use an app (like GitHub Desktop or SourceTree) with a graphical user interface (GUI) to use git, then feel free to do so. But in my experience, it’s worth putting in the effort to learn the terminal commands because 1.) you won’t have to deal with bugs, error messages, and intricate displays to which these apps are prone, and 2.) sometimes (like when working on a remote server or on a different operating system), you won’t be able to use the app anyway.

GitHub registration

Much of the time, you want to be able to share your files (code, documentation, etc) with collaborators, reviewers, readers, or even the rest of the world. GitHub is a great place to do that! In this organization, all of our workshop materials (demos, tutorials, blogs, slides) will be hosted on GitHub so that anyone can access these materials online at any point in the future. In order to make this happen, you will need to:

- Sign up for a GitHub account here

- Join the DukeNeuroMethods Organization!

And that’s it!

Make a repository

To take full reign of the capabilities that git has to offer, you need to make a git repository for your project. There are two ways to do this, depending on whether you want your repository to exist only on your computer or whether you want it to be hosted online through GitHub.

Option 1: keep it local

If you’re the only one that’s going to do anything with your repository, or if the repository contains private information that you don’t want to share with others, then it might make sense to keep the repository local to your computer. In this case, the process for creating a new repository or turning an existing folder into a git repository is easy peasy:

- Open up a terminal and navigate (using

cd) to your project folder - Type in the command

git initand pressEnter

Congrats! You’ve now turned an ordinary folder into a git repository. You should now see that the folder has a sub-folder called .git, which is how you know that this folder is now a git repository.

Option 2: code in the cloud

If you’re going to be working on multiple computers, have multiple collaborators on your project, or simply want an online backup of your repository, then you probably want to put your repository on GitHub:

- Open your browser and navigate to https://github.com/new.

- Enter in the details for your repository. Specifically, you can enter these things:

- Repository name (what you will call your repository)

- Description (a quick summary of what’s in the repository)

- Privacy (public repositories can be seen by anyone, but private repositories can only be seen by collaborators)

READMEfile (a file that has a lengthier description of the repository).gitignorefile (a file that tells git which files to ignore)- License (a file that specifies how others can use your files)

- Click on the

Create repositorybutton - Navigate to the repository in your browser (you may be automatically redirected there)

- Click on

Codeand copy the link underClone with HTTPS - Open a terminal and navigate to wherever you want your repository to go on your computer

- Type in the command

git clone <repository-link>and pressEnter

Congrats! You have now made a repository through GitHub and cloned (downloaded) it onto your computer! If the repository already exists on GitHub and you just need to clone it onto a new computer, you can start from Step 4 above.

Exercise 1: clone this repository!

You may have noticed that this very web-page is located on GitHub within a GitHub repository. To help get some practice using git and GitHub, we’re going to all collaboratively edit this document together. To do this, you first need to clone this repository, which exists online on GitHub, into a copy that exists on your computer. Thankfully, this looks exactly like steps 4-7 above:

- Navigate to the repository in your browser (you may be automatically redirected there)

- Click on

Codeand copy the link underClone with HTTPS- Open a terminal and navigate to wherever you want the repository to go on your computer

- Type in the command

git clone https://github.com/DukeNeuroMethods/git-workshop.gitand pressEnterCongrats! You have cloned this repository on your computer. You should now have a folder with the same name as this repository (

git-workshop). Inside that folder, you will see a copy of this file (README.md), a license file (LICENSE), a.gitfolder, and some other stuff.

Make some changes

The magic of git doesn’t really kick in until your files start changing. In practice, here is when you would add and edit some code, write up some documentation, or put some other kinds of files into your repository. For the purposes of this tutorial, we’re going to ask you to edit this document (README.md):

Exercise 2: edit this tutorial

The very last section of this document has a list of all of the highly esteemed individuals who have completed this tutorial. You might notice that something is missing here- your name! To make sure that everyone knows how skilled and accomplished you are, you need to add yourself to this list. So, here’s what we need to do:

- Open up the file

README.mdin your favorite text editor- Scroll to the very end (the section entitled Declaration of Git Wizardry)

- Add a new line at the end, and type in

- <First Name> <Last Name>Congrats! Now everyone that opens this file on your computer knows that you are a git wizard.

Commit your changes

Now that we’ve made some changes to our repository, we need to make a commit, which is like a “save-point” for our repository. This commit will allow us to recover this version of the repository at any point in the future, even if you have made further changes to these files, or even if you have deleted them completely. As long as your .git subfolder is still there, you can go back to this previous commit.

Exercise 3: stage your changes

To make a new commit, we first have to tell git which changes we want to “save” and which ones we’re not ready to keep yet. In git-lingo, this process is called staging- your staged changes will be added to the next commit, and your unstaged changes will be invisible to that commit.

- Open up a terminal and navigate to your local repository

- Type in the command

git statusto see what changes have been made from the last commit. You should see that this file (README.md) has been modified, but is not yet staged for the next commit.- Type i the command

git add README.md. This will stageREADME.mdfor the next commit. If you have a bunch of changed files, you can use the commandgit add --allto add all of them. Finally, if you only want to stage some of the changes within a given file, you can usegit add --patch <filename>to select the only parts that you want to stage.- Again, type in the command

git statusto make sure that all of (and only) the changes you want to stage are staged.

- If you accidentally staged some changes that you don’t want staged, you can enter the command

git reset HEAD <filename>. This will unstage the file, but keep the changes on your computer.

What just happened? By using git add, we’ve told git that we want to “save” the change we just made. Specifically, we told git that in our next commit, your name will listed at the end of README.md. But, we haven’t yet done the “saving” part- we still need to commit our changes.

Exercise 4: commit your changes

Now that we’ve told git which changes we want to commit and which changes we want to hold out, we can commit our staged changes!

- Open up a terminal and navigate to your local repository

- Type in the command

git statusand pressEnter. You’ll again see all of your staged changes, but this time note that at the top it says something likeOn branch master. Your branch is up to date with 'origin/master'. This lets you know that you don’t have any committed changes that aren’t also on GitHub.- Type in the command

git commit -m "<commit-message>"and pressEnter. The<commit-message>is some description of the changes you are committing, so that if you come back to it later you can remember what you’ve done. If you don’t feel like typing this all out in the terminal, you can just typegit commitby itself, and git will open up a text editor for you to type the message in.- Once again, type in

git statusand pressEnter. This time, you should see that there are no staged or unstaged changes, and at the top it should say something likeOn branch master. Your branch is ahead of 'origin/master' by 1 commit. This lets you know that you have successfully committed your changes and that your committed changes are only visible on your local computer, but not on GitHub.- If you prefer a graphical way of seeing your commit (and other previous commits), you can use the command

git log --all --decorate --oneline --graph. This will print a pretty graph (like the one at the beginning of this tutorial) that shows all previous commits in the order that they were made. If you can’t remember all of those command-line arguments,git logby itself will show you a less-pretty list of previous commits.

Switch between commits

Even though you’ve just committed your changes, it might be hard to tell exactly what just happened. To see what you’ve just done, let’s switch from your current commit to an earlier version of this repository and back.

Exercise 5: virtual time travel

If you’ve run the

git logon this repository, you have seen that your commit isn’t the only one there. There are older versions of this repository as well. To access these older versions, we can use the commandgit checkout:

- Open up a terminal and navigate to your local repository

- Type in the command

git log --all --decorate --oneline --graph. If you scroll to the bottom, you’ll see that the first commit to this repository is commit number9d17d90with the descriptionInitial commit.- To get to that commit, type in the command

git checkout 9d17d90. You will get some warning messages about a ‘detached HEAD’, but you can ignore them for now.- Now inspect your directory (using

lsor through Finder/etc). You should see that some files are missing, and theREADME.mdfile is almost entirely empty. This is how the repository looked when it was first created.- To get back to your new commit, type in the command

git checkout master. You should now see thatREADME.mdagain looks just as it had when you made your last commit.

So now we know what it means to have made a commit- it means that if you’ve got some version of this repository, you can always git log to find that previous commit and git checkout to access it. Pretty nifty stuff!

Pushing and pulling

As you saw with your last git status, even though you have committed the addition of your name to README.md, git told you that this commit is only visible on your local computer. This means that your commit hasn’t been uploaded to GitHub, and consequently, anyone else that cloned the repository will not be able to see your commit. But we don’t just want to tell ourselves that we’re git wizards, we want to tell the world!

In git, we use the words push and pull to signify uploading and downloading, respectively. So git push lets you upload your new commits to GitHub, and git pull lets you download any new commits from GitHub to your local computer.

Exercise 6: share your changes with the world

In order to tell the world that you’re a git wizard, you need to push your new commit to GitHub. But, there’s a catch: if your local repository isn’t up to date with GitHub, then you could overwrite some new commits and cause problems. To avoid messy scenarios like this, always pull before you push. Repeat after me: always pull before you push!

- Open up a terminal and navigate to your local repository

- Enter in the command

git pull origin master, or simplygit pull. Theoriginpart tells git that we want to pull from theoriginremote repository located on GitHub, and themasterpart tells git that we want to pull from themasterbranch

- If you just want to make new changes on GitHub visible without applying those changes, you can use

git fetchinstead ofgit pull- Enter in the command

git status- if nothing went wrong, you should just see that the new commits have been applied. If there are problems, you will get a warning message that there was a “merge conflict”. If that’s the case, then you’re going to want to jump ahead to the section on merging branches together- Now that we know our repository is up to date, we can go ahead and

git push origin master(or simplygit push) to upload our new commits to GitHub- Run

git statusagain, which should tell you something likeOn branch master. Your branch is up to date with 'origin/master'. If you’re still skeptical that your changes have been made, you can go to the repository on GitHub in your browser and check for yourself that your name is here

And that’s that! Now the entire world knows of your great accomplishments!

Git branch: parallel universes

Let’s say you wanted to make some changes in your repository that were going to take a long time, so you want to allow other people to continue working on the current version of your repository, while still being able to commit and push your changes to a separate place on GitHub. This is exactly what git branches are for- they create “parallel universes” of your repository, which allow for different versions of the repository to exist simultaneously.

In a sense, you’ve already been acquainted with branches: you’ve seen that this whole time we’ve been working on, committing to, and pushing to the master branch of this repository. Every repository has a master branch, which serves like a “default” branch or a “main” branch. But, if you want, you can also create other branches too!

Exercise 7: make a branch

To get a sense of how to use branches, we’re going to create a dummy branch, make & commit some changes to it, and then delete it since we don’t really need it after all.

- Open up a terminal and navigate to your local repository

- Type in

git branch --list. This will show you all of the branches that exist for this repository. In this case, you should only see the branchmaster- To create a new branch, type in

git branch <branch-name>and pressEnter- Try

git branch --listagain- you should see that your new branch now appears in this list, but that you’re still working on themasterbranch- To switch to your branch, type in the command

git checkout <branch-name>- If you feel so inclined, try making some changes to this

README.mdfile.

- To commit to this branch, follow the same procedure from Exercises 3-4 using

git addandgit commit- Don’t do this, but if you wanted to push this branch to GitHub, you can use

git pull origin <branch-name>andgit push origin <branch-name>- To delete this branch, first switch back to the

masterbranch usinggit checkout master, then enter the commandgit branch -D <branch-name>

Merging branches

Closing a branch

If you’re done with a branch, you may want to incorporate the changes made in that branch back into the master branch. We’re not going to do an exercise here, but here’s how you can do that:

- Switch back to the

masterbranch usinggit checkout master - Enter the command

git merge <branch-name> - If everything goes well, the merge is successful and a new commit will be made that signals that the two branches were merged.

Updating a branch

If, conversely, you’re still working on your branch but you want to incorporate some new changes on the master branch into your branch, you can do basically the same thing:

- Switch back to your branch using

git checkout <branch-name> - Enter the command

git merge master - If everything goes well, the merge is successful and a new commit will be made that signals that the two branches were merged.

Finally, note that you can update your branch with changes from any other branch, not just the master branch. In that case, just use the proper branch name in your call to git merge.

Merge conflicts

Sometimes, if the set of changes made in the two branches you’re merging are incompatible with each other (say, each branch added a different line to the same file in the same place), you will get a warning that there was a merge conflict. To resolve this conflict, you simply need to choose which version of your file you want to keep.

Exercise 8: resolving a merge conflict

If you got a warning message about a “merge conflict” when you used

git pullto update your local repository with the most up-to-date version on GitHub, it’s probably because someone else put their name in the same place that you did. In order to have both names displayed on this page, we need to resolve this conflict:

- Open up a terminal and navigate to your local repository

- Enter the command

git status- it should tell you that both branches modified the fileREADME.md- Open the

README.mdfile in a text editor of your choice and scroll to where you added your nameYou should see some funky text that looks like this:

<<<<<<< HEAD

- <your name>

=======

- <someone else’s name>

>>>>>>>- The signs

<<<<<<<,=======, and>>>>>>>are markers that tell you where the merge conflict happened, which changes are yours, and which changes are someone else’s. To keep both changes and resolve the conflict, simply delete the lines containing these markers- To continue the merging process, you can either use

git merge --continueorgit commit.

Sadly, the weird world of merge conflicts can get pretty messy, and most merge conflicts won’t be as easy as this to resolve. Still, these basic steps apply: locate the sources of the conflict, choose which set of changes you want, then commit your merged branches to finalize the merge.