Intro to Mixed Effects Regression in R

Welcome! This is an intro-level workshop about mixed effects regression in R. We’ll cover the basics of linear and logit models. You should have an intermediate-level understanding of R and standard linear regression.

Acknowledgments: Adapted from code provided by Gabriela K Hajduk (gkhajduk.github.io), who in turn referenced a workshop developed by Liam Bailey. Parts of the tutorial are also adapted from a lesson on partial pooling by Tristan Mahr.

For further reading, please check out their tutorials and blogs here:

https://gkhajduk.github.io/2017-03-09-mixed-models/

https://www.tjmahr.com/plotting-partial-pooling-in-mixed-effects-models/

Setup

First, we’ll just get everything set up. We need to tweak some

settings, load packages, and read our data.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

#change some settings

options(scipen=999) #turn off scientific notation

options(contrasts = c("contr.sum","contr.poly")) #this tweaks the sum-of-squares settings to make sure the output of Anova(model) and summary(model) are consistent and appropriate when a model has interaction terms

#time to load some packages!

library(lme4) #fit the models

library(lmerTest) #gives p-values and more info

library(car) #more settings for regression output

library(dplyr) #for data wrangling

library(tibble) #for data wrangling

library(sjPlot) #plotting model-predicted values

library(ggplot2) #plotting raw data

library(data.table) #for pretty HTML tables of model parameters

#load the data

dragons <- read.csv("2020-10-21-dragon-data.csv")

Data

Let’s get familiar with our dataset. This is a fictional dataset

about dragons. Each dragon has one row. We have information about each

dragon’s body length and cognitive test score. Let’s say our first

research question is whether the length of the dragon is related to its

intelligence.

We also have some other information about each dragon: We know about the mountain range where it lives, color, diet, and whether or not it breathes fire.

Take a look at the data and check the counts of our variables.

1

2

#take a peek at the header

head(dragons)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

## testScore bodyLength mountainRange color diet breathesFire

## 1 0.0000000 175.5122 Bavarian Blue Carnivore 1

## 2 0.7429138 190.6410 Bavarian Blue Carnivore 1

## 3 2.5018247 169.7088 Bavarian Blue Carnivore 1

## 4 3.3804301 188.8472 Bavarian Blue Carnivore 1

## 5 4.5820954 174.2217 Bavarian Blue Carnivore 0

## 6 12.4536350 183.0819 Bavarian Blue Carnivore 1

1

2

3

4

5

#view the full dataset

#View(dragons)

#check out counts for all our categorical variables

table(dragons$mountainRange)

1

2

3

##

## Bavarian Central Emmental Julian Ligurian Maritime Sarntal Southern

## 60 60 60 60 60 60 60 60

1

table(dragons$diet)

1

2

3

##

## Carnivore Omnivore Vegetarian

## 156 167 157

1

table(dragons$color)

1

2

3

##

## Blue Red Yellow

## 160 160 160

1

table(dragons$breathesFire)

1

2

3

##

## 0 1

## 229 251

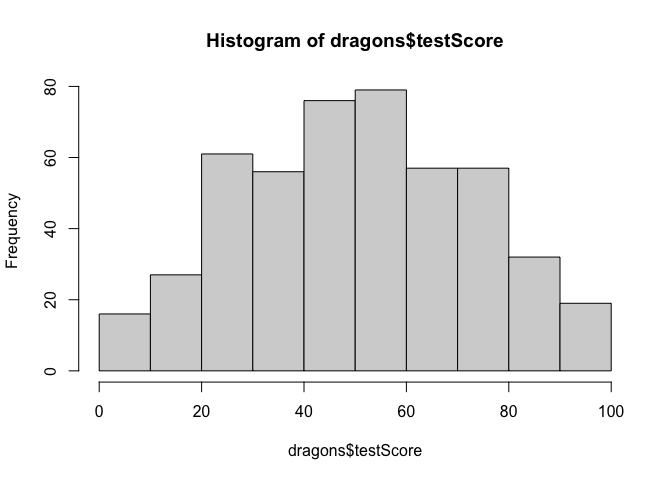

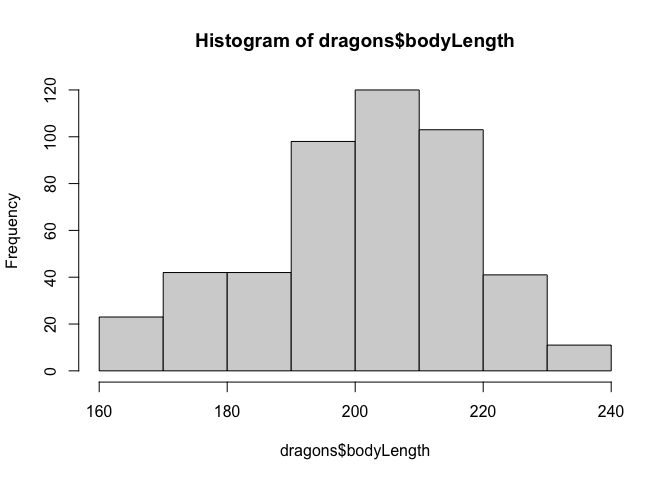

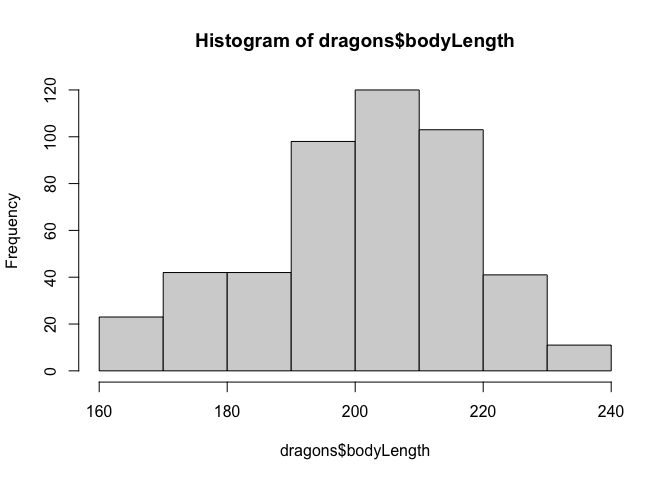

Let’s check distributions. Do test scores and body length measurements look approximately normal?

1

2

#check assumptions: do our continuous variables have approximately normal distributions?

hist(dragons$testScore)

1

hist(dragons$bodyLength)

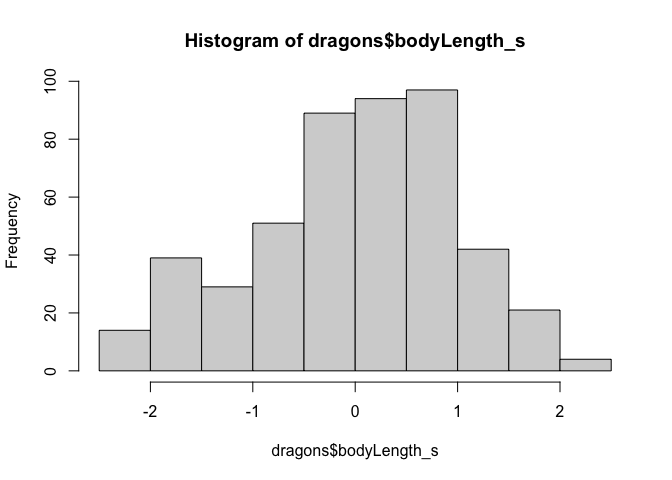

We should mean-center our continuous measure of body length before using it in a model.

1

2

3

4

5

#It is good practice to standardise your explanatory variables before proceeding - you can use scale() to do that:

dragons$bodyLength_s <- scale(dragons$bodyLength)

#Let's look at the histogram again. The scale has changed, so the distribution is now centered around zero.

hist(dragons$bodyLength_s) # seems close to normal distribution - good!

Why do we standardize/mean-center variables? Should we also standardize testScore? Why or why not?

Linear Regression

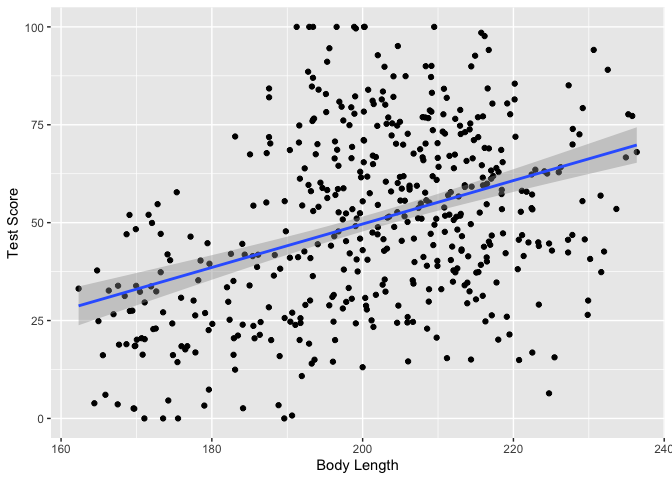

Okay, let’s start fitting some lines! Key Question: Does body

length predict test score?

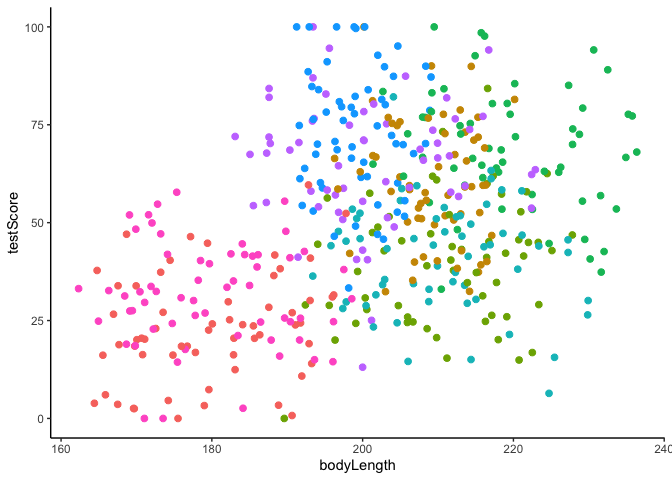

One way to analyse this data would be to try fitting a linear model to all our data, ignoring all the other variables for now.

This is a “complete pooling” approach, where we “pool” together all the data and ignore the fact that some observations came from specific mountain ranges.

1

2

model <- lm(testScore ~ bodyLength_s, data = dragons)

summary(model)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = testScore ~ bodyLength_s, data = dragons)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -56.962 -16.411 -0.783 15.193 55.200

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 50.3860 0.9676 52.072 <0.0000000000000002 ***

## bodyLength_s 8.9956 0.9686 9.287 <0.0000000000000002 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 21.2 on 478 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.1529, Adjusted R-squared: 0.1511

## F-statistic: 86.25 on 1 and 478 DF, p-value: < 0.00000000000000022

Incredible! It’s super significant! We’re gonna publish in Nature Dragonology!

Let’s plot the data with ggplot2 to see the correlation.

1

2

3

4

5

ggplot(dragons, aes(x = bodyLength, y = testScore)) +

geom_point()+

geom_smooth(method = "lm") +

xlab("Body Length")+

ylab("Test Score")

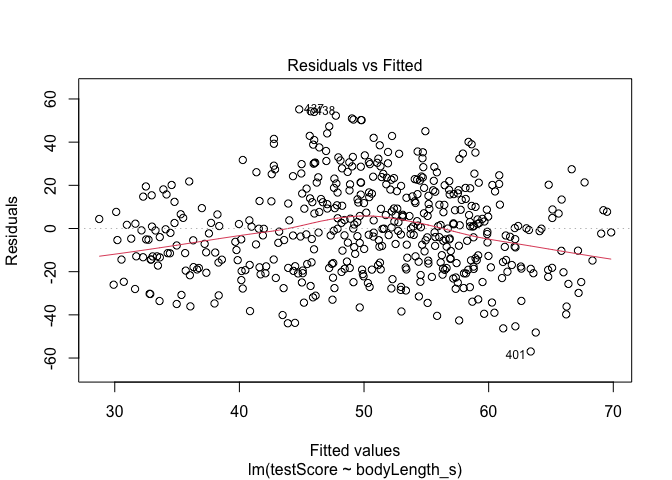

Wait, but we need to check assumptions!

1

2

#Let's plot the residuals from this model. Ideally, the red line should be flat.

plot(model, which = 1) # not perfect, but looks alright

1

2

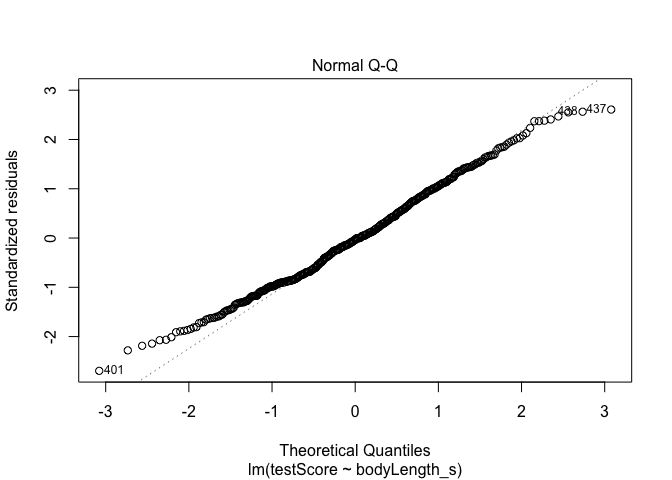

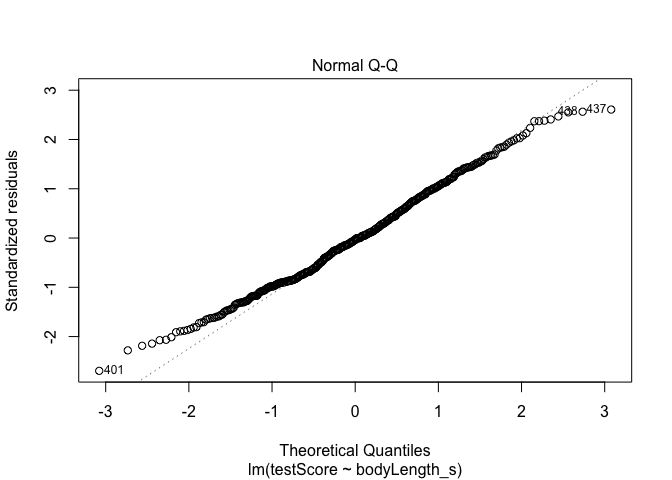

#Have a quick look at the qqplot too - point should ideally fall onto the diagonal dashed line

plot(model, which = 2) # a bit off at the extremes, but that's often the case; again doesn't look too bad

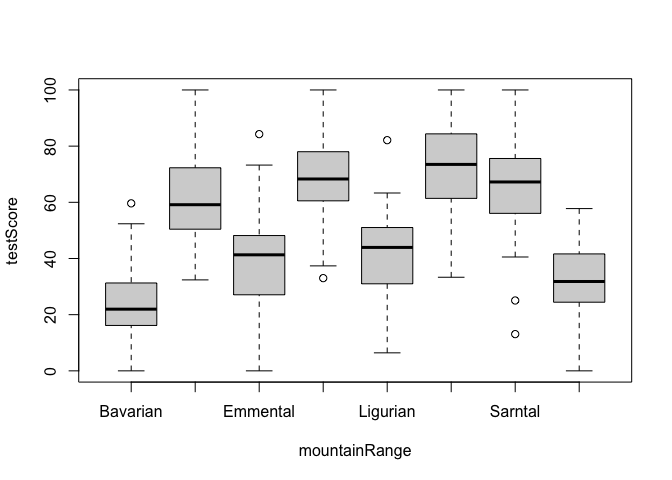

But linear models also assume that observations are INDEPENDENT. Uh oh.

We collected multiple samples from eight mountain ranges. It’s perfectly plausible that the data from within each mountain range are more similar to each other than the data from different mountain ranges - they are correlated. This could be a problem.

1

2

#Have a look at the data to see if above is true

boxplot(testScore ~ mountainRange, data = dragons) # certainly looks like something is going on here

1

2

3

4

5

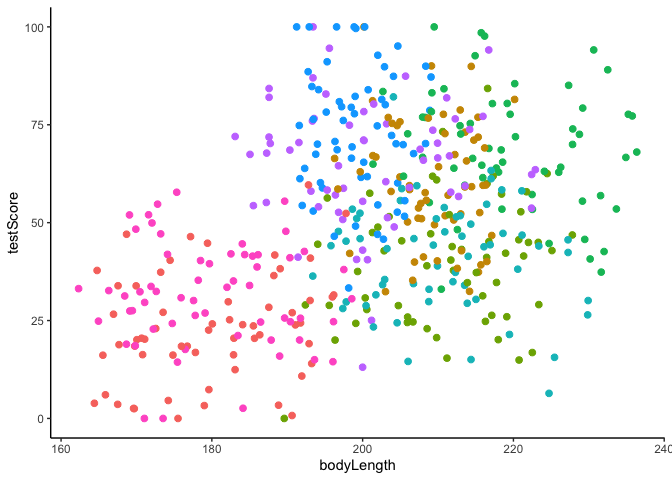

#We could also plot it colouring points by mountain range

ggplot(dragons, aes(x = bodyLength, y = testScore, colour = mountainRange))+

geom_point(size = 2)+

theme_classic()+

theme(legend.position = "none")

Clearly, there is structured variance in our data that has something to do with the mountain range where we found the dragons.

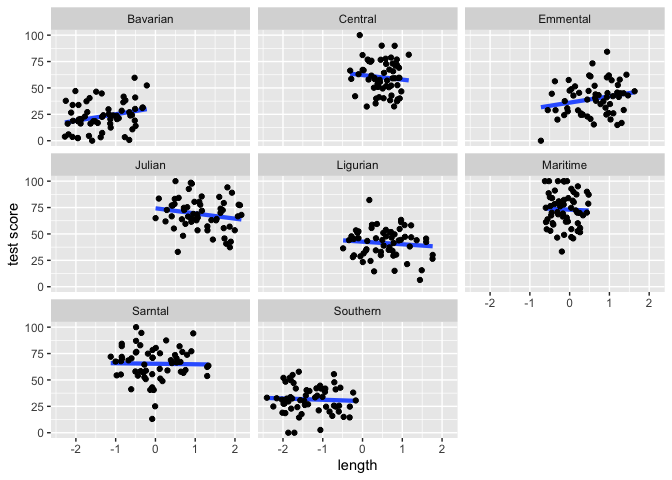

How do we deal with this variance? We could run many separate analyses and fit a regression for each of the mountain ranges. Let’s check what it would look like if we fit a separate regression line for each mountain range.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

#Lets have a quick look at the data split by mountain range

#We use the facet_wrap to do that

ggplot(data = dragons, aes(x = bodyLength_s, y = testScore)) +

stat_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE, size = 1.5) +

geom_point() +

facet_wrap(.~mountainRange) +

xlab("length") + ylab("test score")

From the above plots it looks like our mountain ranges vary both in the dragon body length and in their test scores. This confirms that our observations from within each of the ranges aren’t independent. We can’t ignore that.

So, what if we estimate the effect of bodyLength on testScore for each range independently?

This would be a no-pooling approach: fitting a separate line for each mountain range, and ignoring our group-level information. This approach treats each group of observations (in this case, mountainRange, but could be participants in other datasets) totally independently.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

df_no_pooling <- lmList(testScore ~ bodyLength_s | mountainRange, data = dragons) %>%

coef() %>%

# Mountain Range IDs are stored as row-names above. Let's also add a column to label them.

rownames_to_column("mountainRange") %>%

rename(Intercept = `(Intercept)`, Slope_length = bodyLength_s) %>%

add_column(Model = "No pooling")

head(df_no_pooling)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

## mountainRange Intercept Slope_length Model

## 1 Bavarian 31.20839 6.123797 No pooling

## 2 Central 62.18653 -4.320506 No pooling

## 3 Emmental 36.07089 6.027930 No pooling

## 4 Julian 74.30562 -4.909633 No pooling

## 5 Ligurian 42.67941 -2.475646 No pooling

## 6 Maritime 73.01376 -1.785289 No pooling

Check out the variation in the intercepts and slopes when we fit a separate model for each mountain range.

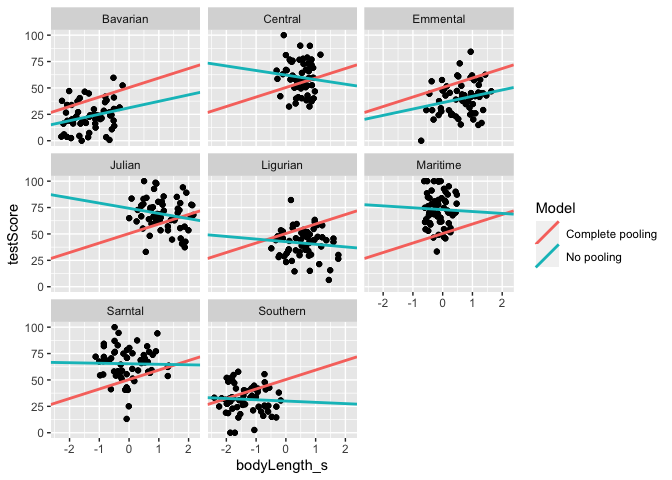

How do our estimates compare for the complete pooling vs. no pooling methods?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

#First, let's grab the coefficients from the first model we fit (the simple linear regression that ignores mountain range information)

df_pooled <- tibble(

Model = "Complete pooling",

mountainRange = unique(dragons$mountainRange),

Intercept = coef(model)[1],

Slope_length = coef(model)[2])

#You can see that this just copies the same group-level line estimate for every mountain range

head(df_pooled)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

## # A tibble: 6 x 4

## Model mountainRange Intercept Slope_length

## <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 Complete pooling Bavarian 50.4 9.00

## 2 Complete pooling Central 50.4 9.00

## 3 Complete pooling Emmental 50.4 9.00

## 4 Complete pooling Julian 50.4 9.00

## 5 Complete pooling Ligurian 50.4 9.00

## 6 Complete pooling Maritime 50.4 9.00

1

2

3

4

#Let's combine this with the estimates from the no-pooling approach

df_models <- bind_rows(df_pooled, df_no_pooling) %>%

left_join(dragons, by = "mountainRange")

head(df_models)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

## # A tibble: 6 x 10

## Model mountainRange Intercept Slope_length testScore bodyLength color diet

## <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <chr>

## 1 Comp… Bavarian 50.4 9.00 0 176. Blue Carn…

## 2 Comp… Bavarian 50.4 9.00 0.743 191. Blue Carn…

## 3 Comp… Bavarian 50.4 9.00 2.50 170. Blue Carn…

## 4 Comp… Bavarian 50.4 9.00 3.38 189. Blue Carn…

## 5 Comp… Bavarian 50.4 9.00 4.58 174. Blue Carn…

## 6 Comp… Bavarian 50.4 9.00 12.5 183. Blue Carn…

## # … with 2 more variables: breathesFire <int>, bodyLength_s[,1] <dbl>

1

2

3

4

5

#Let's plot the two linear estimates for each mountain range

ggplot(data = df_models, aes (x = bodyLength_s, y = testScore)) +

geom_point() +

geom_abline(aes(intercept = Intercept, slope = Slope_length, color = Model), size = 1)+

facet_wrap(.~mountainRange)

We got very different estimates from the two different approaches. Is there a happy medium?

Linear Mixed Effects Regression

Mountain range clearly introduces a structured source of variance

in our data. We need to control for that variation if we want to

understand whether body length really predicts test scores.

But it doesn’t really make sense to estimate the effect for each mountain range separately. Shouldn’t we use the full power of our whole dataset?

Mixed effects regression is a compromise: Partial pooling! We can let

each mountain range have it’s own regression line, but make an informed

guess about that line based on the group-level estimates This is

especially useful when some groups/participants have incomplete data.

Should Mountain Range be a FIXED or RANDOM effect?

We could consider it a FIXED EFFECT if we were interested in testing the hypothesis that location of residence influences test scores– but that’s not our research question! This is just annoying noise that limits our ability to test the relationship between body length and test scores. So, we need to account for structured variance among mountain ranges by modelling it as a RANDOM EFFECT.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

#let's fit our first mixed model!

mixed_model <- lmer(testScore ~ bodyLength_s + (1+bodyLength_s|mountainRange), data = dragons)

#note that you might get a "singular fit" warning --> In this case, it's because the data are made-up and we've got some weird correlations in our random effects structure. If you get this with real data, it's not necessarily terrible, but it indicates that you should check for either very high or very low covariance, and try modifying your random effects structure.

#what's the verdict?

summary(mixed_model)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

## Linear mixed model fit by REML. t-tests use Satterthwaite's method [

## lmerModLmerTest]

## Formula: testScore ~ bodyLength_s + (1 + bodyLength_s | mountainRange)

## Data: dragons

##

## REML criterion at convergence: 3980.5

##

## Scaled residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -3.5004 -0.6683 0.0207 0.6592 2.9449

##

## Random effects:

## Groups Name Variance Std.Dev. Corr

## mountainRange (Intercept) 324.102 18.003

## bodyLength_s 9.905 3.147 -1.00

## Residual 221.578 14.885

## Number of obs: 480, groups: mountainRange, 8

##

## Fixed effects:

## Estimate Std. Error df t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 51.75302 6.40349 6.91037 8.082 0.0000916 ***

## bodyLength_s -0.03326 1.68317 10.22337 -0.020 0.985

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Correlation of Fixed Effects:

## (Intr)

## bodyLngth_s -0.674

## convergence code: 0

## boundary (singular) fit: see ?isSingular

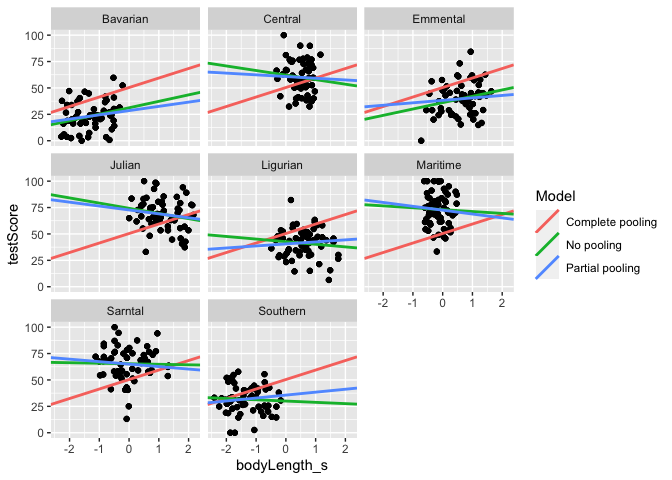

Now, let’s see how these lines compare to the no-pooling method.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

#save the coefficients from our mixed model

df_partial_pooling <- coef(mixed_model)[["mountainRange"]] %>%

rownames_to_column("mountainRange") %>%

as_tibble() %>%

rename(Intercept = `(Intercept)`, Slope_length = bodyLength_s) %>%

add_column(Model = "Partial pooling")

#take a peek

head(df_partial_pooling)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

## # A tibble: 6 x 4

## mountainRange Intercept Slope_length Model

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <chr>

## 1 Bavarian 28.5 4.02 Partial pooling

## 2 Central 60.8 -1.62 Partial pooling

## 3 Emmental 38.2 2.33 Partial pooling

## 4 Julian 72.7 -3.70 Partial pooling

## 5 Ligurian 40.6 1.92 Partial pooling

## 6 Maritime 72.5 -3.66 Partial pooling

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

#add these estimates to our dataframe

df_models <- bind_rows(df_pooled, df_no_pooling, df_partial_pooling) %>%

left_join(dragons, by = "mountainRange")

#Let's plot the three linear estimates for each mountain range

ggplot(data = df_models, aes (x = bodyLength_s, y = testScore)) +

geom_point() +

geom_abline(aes(intercept = Intercept, slope = Slope_length, color = Model), size = 1)+

facet_wrap(.~mountainRange)

You can see that we get different estimates from all three approaches. Partial pooling yields lines that are tailored to each participant, but still influenced by the pooled group data.

Overall, it looks like when we account for the effect of mountain range, there is no relationship between body length and test scores. Well, so much for our Nature Dragonology paper!

Unless… What about our other variables? Let’s test whether diet is related to test scores instead.

1

2

3

4

mixed_model <- lmer(testScore ~ diet + (1+diet|mountainRange), data = dragons)

#view output

Anova(mixed_model, type=3)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

## Analysis of Deviance Table (Type III Wald chisquare tests)

##

## Response: testScore

## Chisq Df Pr(>Chisq)

## (Intercept) 186.75 1 < 0.00000000000000022 ***

## diet 130.55 2 < 0.00000000000000022 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

1

summary(mixed_model)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

## Linear mixed model fit by REML. t-tests use Satterthwaite's method [

## lmerModLmerTest]

## Formula: testScore ~ diet + (1 + diet | mountainRange)

## Data: dragons

##

## REML criterion at convergence: 3659.7

##

## Scaled residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -2.6961 -0.6041 -0.0268 0.5114 4.5041

##

## Random effects:

## Groups Name Variance Std.Dev. Corr

## mountainRange (Intercept) 100.765 10.038

## diet1 6.315 2.513 -0.09

## diet2 24.214 4.921 0.88 -0.56

## Residual 113.340 10.646

## Number of obs: 480, groups: mountainRange, 8

##

## Fixed effects:

## Estimate Std. Error df t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 49.186 3.599 6.749 13.666 0.00000362 ***

## diet1 -15.125 1.332 5.066 -11.354 0.00008537 ***

## diet2 15.028 1.989 6.418 7.554 0.000202 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Correlation of Fixed Effects:

## (Intr) diet1

## diet1 -0.044

## diet2 0.760 -0.573

## convergence code: 0

## boundary (singular) fit: see ?isSingular

What did we find?

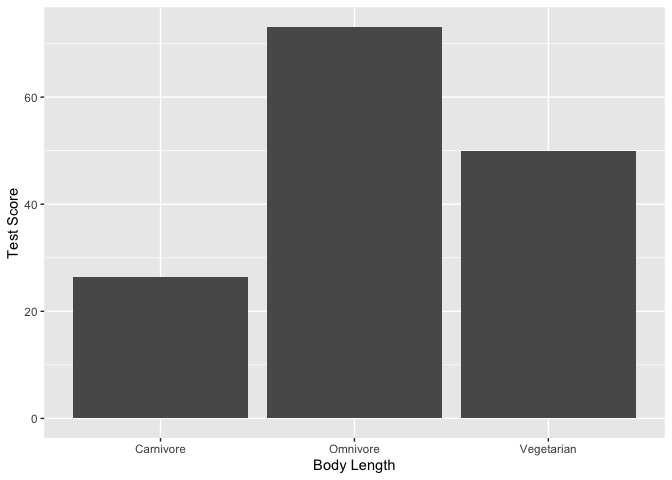

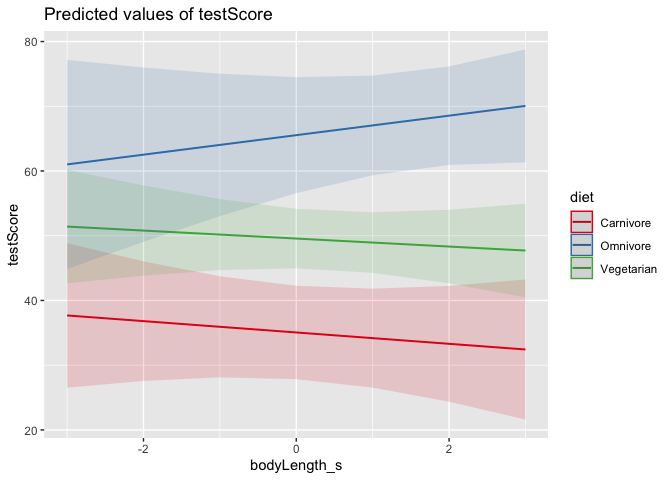

Let’s visualize the effect of diet on test scores.

1

2

3

4

5

#Plot average test score by diet type

ggplot(dragons, aes(x = diet, y = testScore)) +

geom_bar(stat = "summary")+

xlab("Body Length")+

ylab("Test Score")

1

2

3

4

5

6

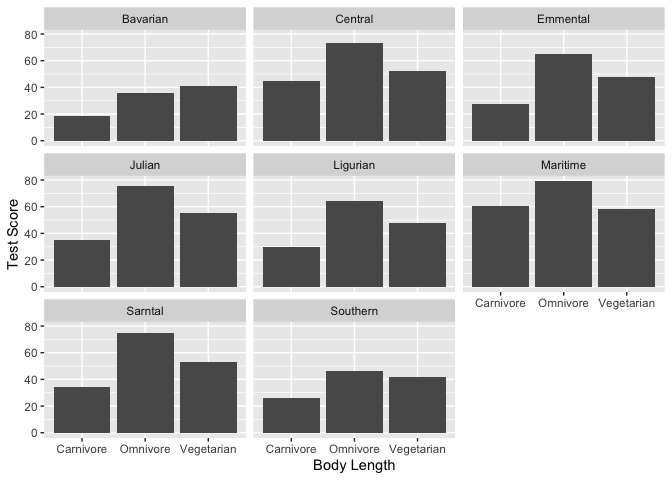

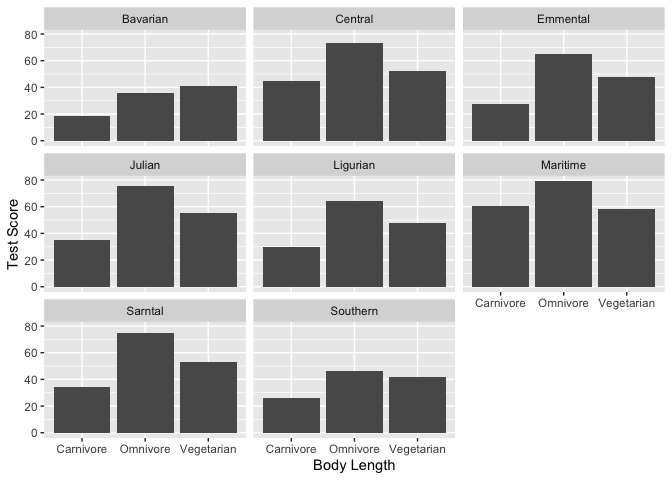

#Let's also look at the effect across mountain ranges.

ggplot(dragons, aes(x = diet, y = testScore)) +

geom_bar(stat = "summary")+

xlab("Body Length")+

ylab("Test Score") +

facet_wrap(.~mountainRange)

Looks pretty consistent, but there’s obviously still variability between mountains.

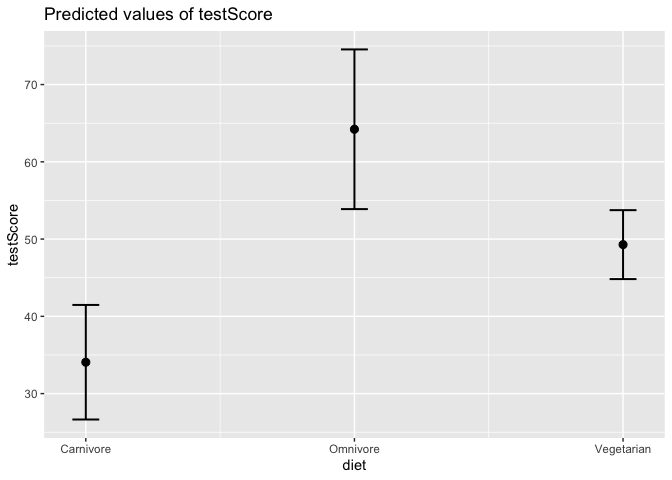

Let’s also plot the predicted values from our mixed effects model, so we can control for the effect of mountain range.

1

plot_model(mixed_model, type = "pred", terms = "diet")

Awesome, we will want to put this finding in our Nature Dragonology paper! Let’s clean up the output.

1

2

#Generate an HTML table with parameter estimates

tab_model(mixed_model, p.val = "satterthwaite", show.df = TRUE, p.style="numeric_stars", show.fstat = TRUE)

| testScore | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | CI | p | df |

| (Intercept) | 49.19 *** | 42.13 – 56.24 | <0.001 | 8.40 |

| diet1 | -15.13 *** | -17.74 – -12.51 | <0.001 | 11.39 |

| diet2 | 15.03 *** | 11.13 – 18.93 | <0.001 | 50.89 |

| Random Effects | ||||

| σ2 | 113.34 | |||

| τ00 mountainRange | 100.76 | |||

| τ11 mountainRange.diet1 | 6.32 | |||

| τ11 mountainRange.diet2 | 24.21 | |||

| ρ01 | -0.09 | |||

| 0.88 | ||||

| N mountainRange | 8 | |||

| Observations | 480 | |||

| Marginal R2 / Conditional R2 | 0.575 / NA | |||

| * p<0.05 ** p<0.01 *** p<0.001 | ||||

What if we want to test multiple variables at the same time?

1

2

mixed_model <- lmer(testScore ~ diet * bodyLength_s + (1+diet*bodyLength_s|mountainRange), data = dragons)

Anova(mixed_model, type=3)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

## Analysis of Deviance Table (Type III Wald chisquare tests)

##

## Response: testScore

## Chisq Df Pr(>Chisq)

## (Intercept) 222.4446 1 <0.0000000000000002 ***

## diet 151.3960 2 <0.0000000000000002 ***

## bodyLength_s 0.0000 1 0.9966

## diet:bodyLength_s 2.3406 2 0.3103

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

1

summary(mixed_model)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

## Linear mixed model fit by REML. t-tests use Satterthwaite's method [

## lmerModLmerTest]

## Formula: testScore ~ diet * bodyLength_s + (1 + diet * bodyLength_s |

## mountainRange)

## Data: dragons

##

## REML criterion at convergence: 3651.9

##

## Scaled residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -2.8679 -0.5963 -0.0339 0.5147 4.4547

##

## Random effects:

## Groups Name Variance Std.Dev. Corr

## mountainRange (Intercept) 86.966 9.326

## diet1 5.002 2.236 0.07

## diet2 13.235 3.638 0.84 -0.48

## bodyLength_s 1.920 1.386 -0.84 0.48 -1.00

## diet1:bodyLength_s 1.092 1.045 0.18 0.99 -0.38 0.37

## diet2:bodyLength_s 1.070 1.034 -1.00 -0.05 -0.85 0.85

## Residual 113.570 10.657

##

##

##

##

##

##

## -0.17

##

## Number of obs: 480, groups: mountainRange, 8

##

## Fixed effects:

## Estimate Std. Error df t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 50.052784 3.355964 6.082433 14.915 0.00000509 ***

## diet1 -14.996045 1.287080 2.975401 -11.651 0.00141 **

## diet2 15.484451 1.604576 3.507999 9.650 0.00120 **

## bodyLength_s 0.004232 1.002688 10.623582 0.004 0.99671

## diet1:bodyLength_s -0.880429 0.934680 8.397553 -0.942 0.37252

## diet2:bodyLength_s 1.502019 0.991514 15.581988 1.515 0.14982

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Correlation of Fixed Effects:

## (Intr) diet1 diet2 bdyLn_ dt1:L_

## diet1 0.075

## diet2 0.659 -0.543

## bodyLngth_s -0.424 0.221 -0.435

## dt1:bdyLng_ 0.153 0.409 -0.158 0.059

## dt2:bdyLng_ -0.413 -0.124 -0.323 0.285 -0.500

## convergence code: 0

## boundary (singular) fit: see ?isSingular

Looks like the effect of diet is still significant after we control for body length. We can also see that there’s no significant interaction between diet and body length.

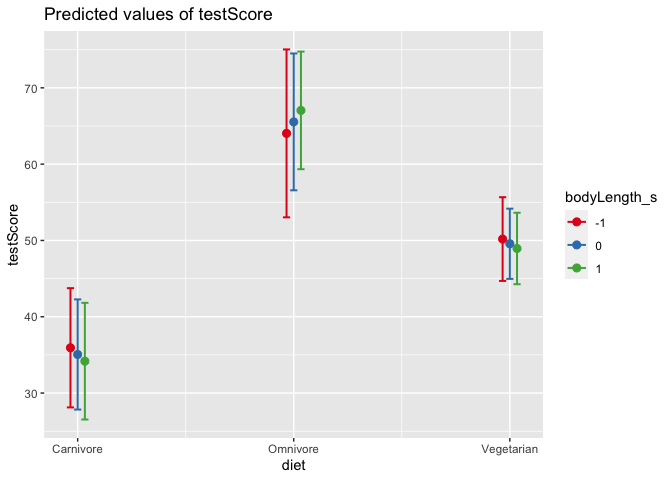

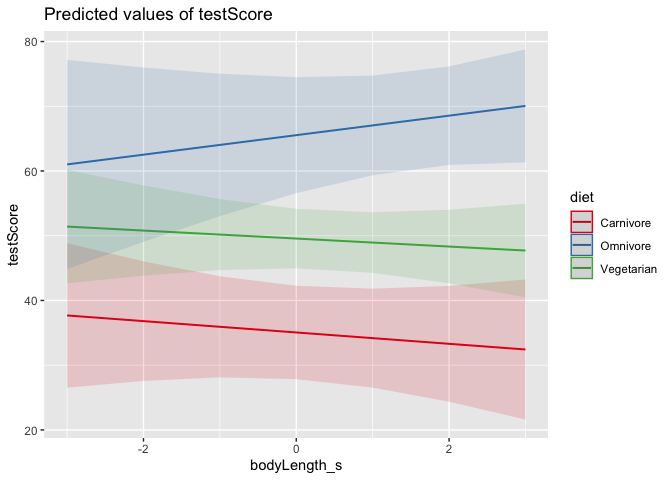

Let’s plot the output again. We can also add multiple terms to our plot of model-predicted values. This is especially helpful when you DO have a significant interaction, and you need to understand why!

1

plot_model(mixed_model, type = "pred", terms = c("diet", "bodyLength_s"))

1

2

3

4

#What are the -1, 0, and +1 levels?

#What happens if we swap the order of the terms?

plot_model(mixed_model, type = "pred", terms = c("bodyLength_s", "diet"))

Which version of the plot makes more sense to you?

Your turn! Try modifying the model above to test whether color is related to testScore, and whether color interacts with diet or bodyLength.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

#Build your model here

#View the output of the model here

#Plot your results below:

Mixed Effects Logistic Regression

Okay, let’s test a new question. Test scores are lame. I actually want to know about which dragons breathe fire. This has way more important practical implications, and is more likely to get me grant funding.

Good news: we have data on fire breathing! Bad news: It’s a binary variable, so we need to change our model.

1

2

logit_model <- glmer(breathesFire ~ color + (1+color|mountainRange), data = dragons, family = binomial)

summary(logit_model)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

## Generalized linear mixed model fit by maximum likelihood (Laplace

## Approximation) [glmerMod]

## Family: binomial ( logit )

## Formula: breathesFire ~ color + (1 + color | mountainRange)

## Data: dragons

##

## AIC BIC logLik deviance df.resid

## 423.1 460.7 -202.6 405.1 471

##

## Scaled residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -3.0000 -0.3083 0.3333 0.3333 4.1246

##

## Random effects:

## Groups Name Variance Std.Dev. Corr

## mountainRange (Intercept) 0.08865 0.2977

## color1 0.08866 0.2978 -1.00

## color2 0.52397 0.7239 0.51 -0.51

## Number of obs: 480, groups: mountainRange, 8

##

## Fixed effects:

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## (Intercept) 0.03662 0.18434 0.199 0.843

## color1 2.16061 0.23902 9.039 <0.0000000000000002 ***

## color2 0.32093 0.31429 1.021 0.307

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Correlation of Fixed Effects:

## (Intr) color1

## color1 -0.246

## color2 0.019 -0.323

## convergence code: 0

## boundary (singular) fit: see ?isSingular

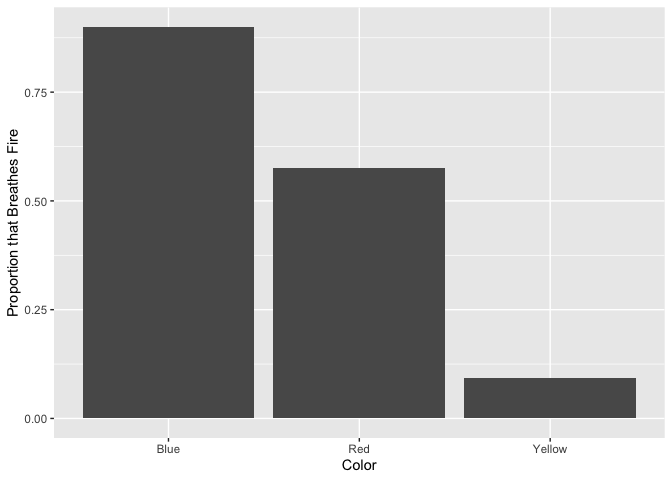

Let’s plot the proportion of dragons that breathe fire by color.

1

2

3

4

ggplot(dragons, aes(x = color, y = breathesFire)) +

geom_bar(stat = "summary")+

xlab("Color") +

ylab("Proportion that Breathes Fire")

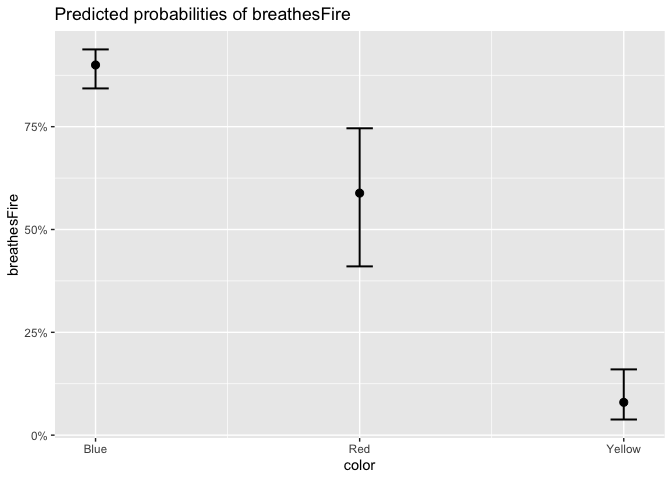

Let’s also get the predicted values from our mixed effects model, so we can control for the effect of mountain range.

1

plot_model(logit_model, type = "pred", terms = "color")

1

2

#generate an HTML table with parameter estimates

tab_model(logit_model, show.df = TRUE, p.style="numeric_stars", show.fstat = TRUE)

| breathesFire | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Odds Ratios | CI | p | df |

| (Intercept) | 1.04 | 0.72 – 1.49 | 0.843 | Inf |

| color1 | 8.68 *** | 5.43 – 13.86 | <0.001 | Inf |

| color2 | 1.38 | 0.74 – 2.55 | 0.307 | Inf |

| Random Effects | ||||

| σ2 | 3.29 | |||

| τ00 mountainRange | 0.09 | |||

| τ11 mountainRange.color1 | 0.09 | |||

| τ11 mountainRange.color2 | 0.52 | |||

| ρ01 | -1.00 | |||

| 0.51 | ||||

| ICC | 0.11 | |||

| N mountainRange | 8 | |||

| Observations | 480 | |||

| Marginal R2 / Conditional R2 | 0.496 / 0.553 | |||

| * p<0.05 ** p<0.01 *** p<0.001 | ||||

Your turn! Test whether other variables predict breathesFire.

1

2

3

4

5

#Build your model here:

#Plot your results:

Convergence

Some parting tips and tricks:

If you ever encounter an error message about “convergence failure,” you cannot trust the results of your model! What can you do to fix this error?

First, check that your continuous predictor variables are all scaled/mean-centered.

Make sure your random effects structure is correct. Are you accidentally specifying random effects that don’t make sense for the data? For example, you can never use a between-subs variable as a random slope when you have a random intercept term for subjects. That wouldn’t make sense, because you only have one observation per subject.

You can also try simplifying your random effects structure. You can start with a maximal model (all possible random slopes and intercepts), and then incrementally prune away random effects terms (starting with interactions in random slopes, etc.) until you achieve convergence. You can also formally compare model fits to determine the optimal random effects structure that is justified by the data.

Lastly, you may need to change the settings of your model and increase

the maximum number of iterations. Adding the following code within your

lmer() call may help: control=lmerControl(optimizer=“bobyqa”, optCtrl=list(maxfun=10e4))

Check that your random effects variables have at least 5 levels each (e.g., 5+ subjects, 5+ observation sites, etc.)

If these tricks still doesn’t help, it may be that you just don’t have enough data to fit the model appropriately! You must have enough observations for every combination of fixed and random effect in order to estimate the variance. You may need to get more data, or prune your model to remove interaction terms that may be causing the problem. For example, a 2x2 interaction term between factor variables assumes that you have data for all 4 possible combinations. If you add more and more interactions, you’re creating a lot of cells that you need to fill.

1

hist(dragons$bodyLength)

Why do we standardize/mean-center variables? Should we also standardize testScore? Why or why not?

1

2

#Have a quick look at the qqplot too - point should ideally fall onto the diagonal dashed line

plot(model, which = 2) # a bit off at the extremes, but that's often the case; again doesn't look too bad

1

2

3

4

5

#We could also plot it colouring points by mountain range

ggplot(dragons, aes(x = bodyLength, y = testScore, colour = mountainRange))+

geom_point(size = 2)+

theme_classic()+

theme(legend.position = "none")

Clearly, there is structured variance in our data that has something to do with the mountain range where we found the dragons.

From the above plots it looks like our mountain ranges vary both in the dragon body length and in their test scores. This confirms that our observations from within each of the ranges aren’t independent. We can’t ignore that.

We got very different estimates from the two different approaches. Is there a happy medium?

You can see that we get different estimates from all three approaches. Partial pooling yields lines that are tailored to each participant, but still influenced by the pooled group data.

1

2

3

4

5

6

#Let's also look at the effect across mountain ranges.

ggplot(dragons, aes(x = diet, y = testScore)) +

geom_bar(stat = "summary")+

xlab("Body Length")+

ylab("Test Score") +

facet_wrap(.~mountainRange)

Looks pretty consistent, but there’s obviously still variability between mountains.

1

2

3

4

#What are the -1, 0, and +1 levels?

#What happens if we swap the order of the terms?

plot_model(mixed_model, type = "pred", terms = c("bodyLength_s", "diet"))

Which version of the plot makes more sense to you?

1

2

#generate an HTML table with parameter estimates

tab_model(logit_model, show.df = TRUE, p.style="numeric_stars", show.fstat = TRUE)

| breathesFire | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Odds Ratios | CI | p | df |

| (Intercept) | 1.04 | 0.72 – 1.49 | 0.843 | Inf |

| color1 | 8.68 *** | 5.43 – 13.86 | <0.001 | Inf |

| color2 | 1.38 | 0.74 – 2.55 | 0.307 | Inf |

| Random Effects | ||||

| σ2 | 3.29 | |||

| τ00 mountainRange | 0.09 | |||

| τ11 mountainRange.color1 | 0.09 | |||

| τ11 mountainRange.color2 | 0.52 | |||

| ρ01 | -1.00 | |||

| 0.51 | ||||

| ICC | 0.11 | |||

| N mountainRange | 8 | |||

| Observations | 480 | |||

| Marginal R2 / Conditional R2 | 0.496 / 0.553 | |||

| * p<0.05 ** p<0.01 *** p<0.001 | ||||