Typesetting with LaTeX

Introduction

A Brief History of Typesetting

Manual Typesetting

(1000/1450 CE–Late 1800s)

Composing stick and type cases

For the longest time, printing text required authors ("compositors") to line up metal character molds ("sorts") one by one to form words, lines, and then pages on metal racks ("composing sticks").

Hot Metal Typesetting

(Late 1800s–Early 1900s)

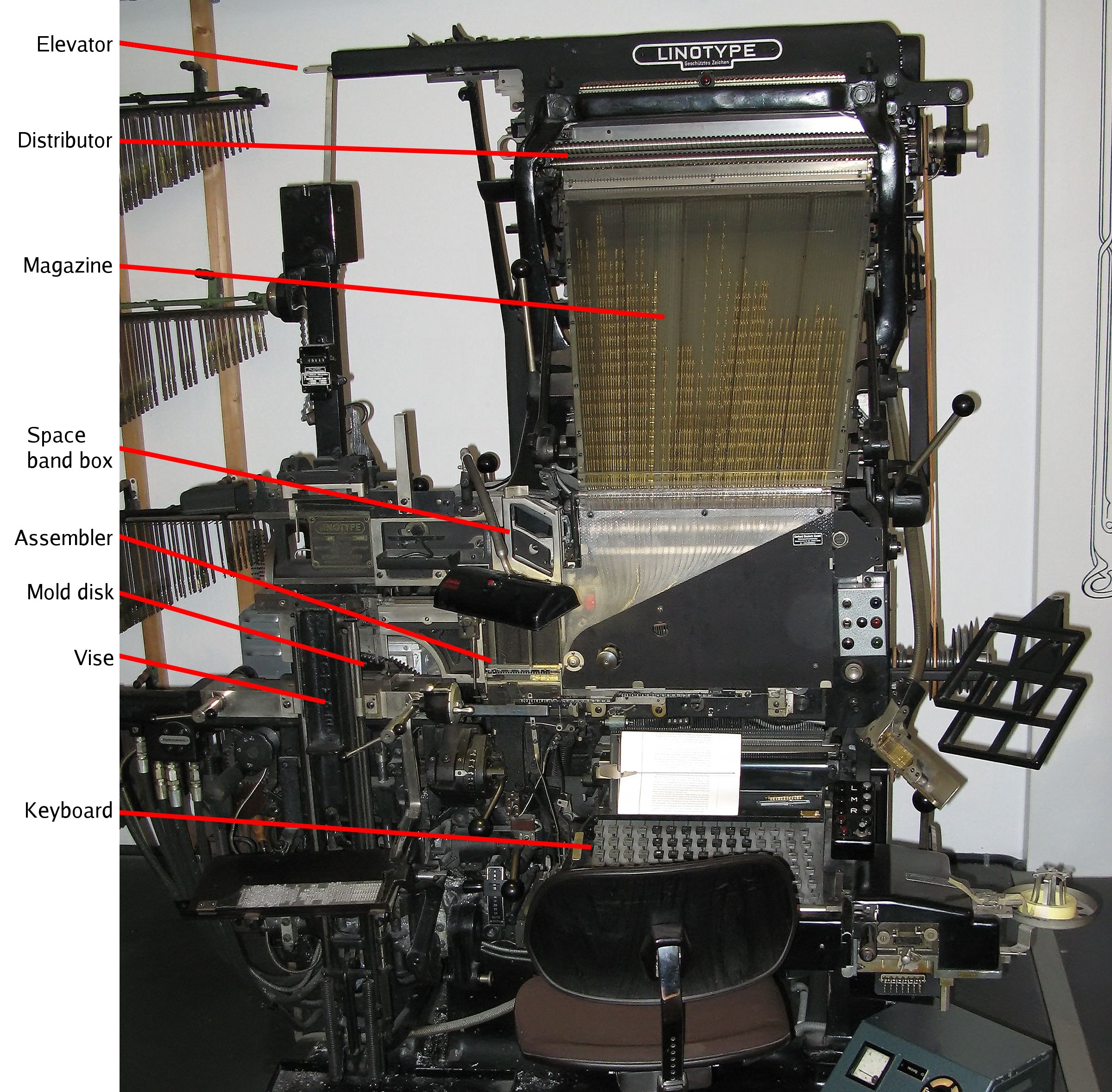

Linotype Model 5cS

Instead of manually assembling by hand text to be printed character by character, people were finally able to type in the letter sequences they wanted to form. Still, the text wasn't directly imprinted on each keypress. Rather, the characters would be entered into a queue forming a "matrix" to be cast as a sequence of characters on one big metal block called a "slug."

Phototypesetting

(1960s–1980s)

Linotype CRTronic 360

Characters from font sets inscribed on glass strips were transcribed by light exposure onto light-sensitive paper. The process was conducted first via punched tape before the introduction of computers.

TeX and LaTeX

(1970s–Present Day)

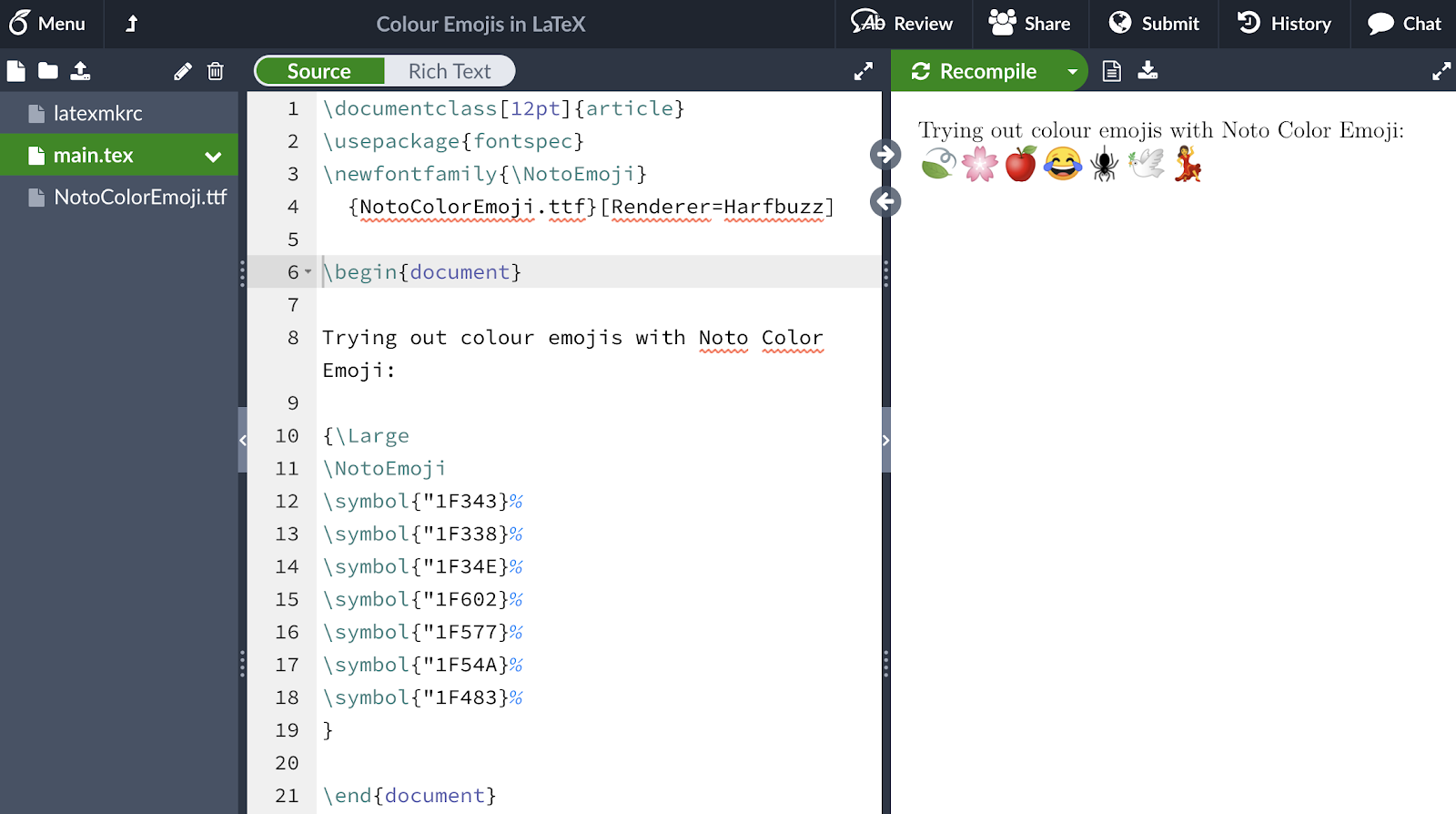

Overleaf

The TeX typesetting system was developed and then popularized through the LaTeX macro package. Today, people generally prepare documents in LaTeX using GUIs.

WYSIWYG

(1980s–Present Day)

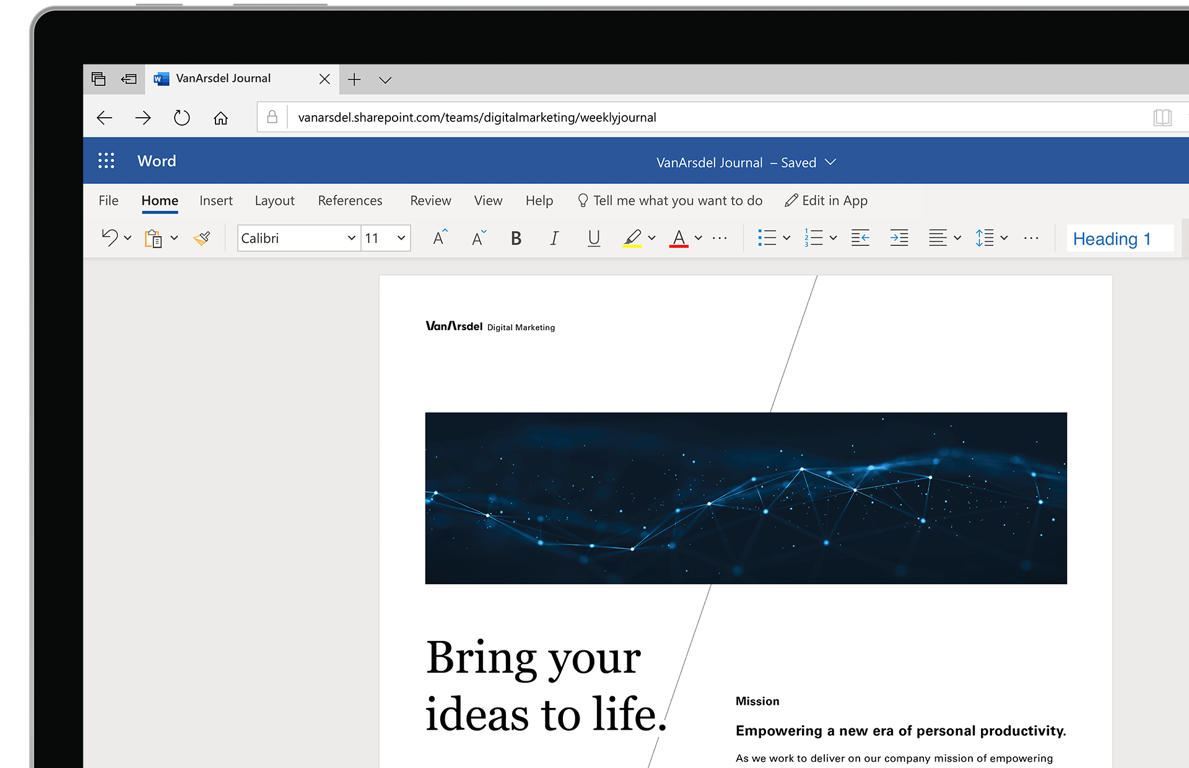

Microsoft Word

The invention of intuitive word processing systems enabled desktop publishing for straightforward document preparation. While these types of software do not offer the same amount of fine-grain control over typography as TeX/LaTeX, they get the job done with very little onboarding.

What is \(\LaTeX\)?

Mind the case-sensitive spelling (and pronunciation).

\(\LaTeX\) is an open-source typesetting software for styling plain-text with markup conventions. It’s a direct alternative to “what you see is what you get” (literally: “WYSIWYG”) document preparation software—which is usually proprietary like MS Word, although not always (e.g., Google Docs). In other words, it’s a programmatic way to format a document (articles and presentations).

It’s most commonly either pronounced “LAH-teck” (/ˈlɑːtɛx/) or the equally acceptable “LAY-teck” (/ˈleɪtɛk/)—the latter being my preferred choice for clarity’s sake, although technically it should be the first. I’ve also heard of “luh-TECK”, but that might be a one-off…

A model of content authoring. We love our Freudian icebergs.

I understand that this supposed “definition” might be quite confusing at first blush, so I think a much better way to conceptualize this is through examples:

- LaTeX (Source Code) → Markdown (WYSIWYM) → Microsoft Word/PowerPoint (WYSIWYG)

- HTML (Source Code) → Wix/Squarespace/WordPress (WYSIWYG)

Just as a website contains plain text—just the actual characters you see on the screen—that has been styled with CSS and JavaScript, LaTeX involves styling plain text with commands known technically as macros (more on this later).

Why (Not) Use \(\LaTeX\)?

The million dollar question. There’s generally a clear answer for when you could (and, as TeX users will argue, therefore, should) or shouldn’t use LaTeX, but there’s also some limited grey area in between where it’ll be up to your discretion whether to opt for a WYSIWYG editor instead.

Advantages:

- Produces the highest quality PDF documents

- Separates content and formatting

- By far the best system for formatting complex mathematical formulas

- Highly effective for managing bibliographies

- More frequently used in the natural sciences

- Open-source (free), huge support community, and thousands of packages

- Old, so 99.9% of questions have already been answered online

- Built on the ideal of backcompatibility

- Modular, can quickly format repeated sections

- Great for:

- Manuscripts

- CVs and Resumes

- Poster Presentations

- Slideshows

- Exams

Disadvantages:

- Tough initial learning curve

- Modifying document layout is not just a click away—it wasn’t designed for this purpose!

- Complicates collaboration as it is not as commonly used by social scientists or the general populace

- (Generally) not great for:

- Flyers

- Advertisements

- Visually complex presentations (e.g., animations)

*MS Word vs. LaTeX

- Collaborators

- What’s best for you may very well depend on what’s best for your collaborators. Science is a team sport, and it would never make sense to insist on using something as fancy as LaTeX to draft a manuscript unless everyone were comfortable with it.

- If everyone on your team wants to use LaTeX, however, there are platforms which readily support real-time collaboration on TeX files—the most popular of these being Overleaf.

- Functionality

- LaTeX was designed for typesetting professional documents. If you’re creating a promotional flyer with a freeform layout, I would absolutely not recommend turning to LaTeX. In fact, I would recommend turning to the other extreme with even more WYSIWYG alternatives than MS Office such as Figma.

- Efficiency

- While MS Word allows you to quickly edit a document and get it “up and running” with drag and drop GUI functionality, formatting can become messy, disorganized, and difficult to reproduce at scale with increasing complexity.

- There are hundreds upon hundreds of freely reusable templates posted online, so unless you’re starting from scratch, you should always check to see if someone has already done the first few steps for you.

*I use MS Word as the canonical WYSIWYG comparison exemplar, but LaTeX offers general parallel (although not necessarily specialized) functionality to a wide range of other software such as MS PowerPoint, Adobe XD, etc.

LaTeX is almost certainly harder to learn from the get-go than portrayed here, but the trend is arguably quite accurate.

Why is LaTeX stylized as \(\LaTeX\)?

“[…] it’s important to notice another thing about TeX’s name: The E is out of kilter. This displaced E is a reminder that TeX is about typesetting, and it distinguishes TeX from other system names. In fact, TEX (pronounced tecks) is the admirable Text EXecutive processor developed by Honeywell Information Systems. Since these two system names are pronounced quite differently, they should also be spelled differently. The correct way to refer to TeX in a computer file, or when using some other medium that doesn’t allow lowering of the E, is to type TeX. Then there will be no confusion with similar names, and people will be primed to pronounce everything properly.”

The font, by the way, is called “Computer Modern” and was designed by Donald Knuth himself. If you see any documents formatted online with this earmark typography, you’ll know it was formatted in LaTeX!

\(\TeX\) vs. \(\LaTeX\)

The distinction between TeX and LaTeX is of the utmost confusion to a lot of people—for good reason! As long as you understand what TeX is, you’ll almost certainly never have to deal with it. LaTeX was designed specifically to harness TeX functionality in a more user-friendly way. In other words, TeX controls underlying layout, LaTeX determines content preparation.

To understand this relationship, we can again turn to a more familiar example:

- LaTeX is built on TeX macros → Python Standard Library is built on C

“Think of LaTeX as a house built with the lumber and nails provided by TeX. You don’t need lumber and nails to live in a house, but they are handy for adding an extra room. Most LaTeX users never need to know any more about TeX commands than they can learn from this book.”

The Men Behind the Madness

Donald Knuth set out to develop TeX during his sabbatical, but he ended up taking nearly a decade to complete the project. He was motivated to do so after receiving from the publisher a very poorly formatted second edition for one of his books.

Leslie Lamport independently wrote his own macros for TeX which he was convinced to document and package into LaTeX. Today, however, basically everyone today actually uses a version called LATEX2ε subsequently released and updated by a team of developers.

The “TeX” portion of the name LaTeX comes from the Ancient Greek word “\(τέχνη\)” meaning “art,” “craft,” or “workmanship.” The “La” comes from Leslie Lamport’s surname, so it’s a portmanteau of “Lamport” + “TeX” = (La)mport’s (TeX) = LaTeX

A Note on Gatekeeping and Necessity

Before we progress through the rest of this tutorial, I just want to note: no matter what “experts” may furiously argue on online forums, LaTeX is entirely not something you need to learn, even as neuroscientists. Is it a great tool that can help you tremendously with scientific writing? Absolutely. But, this in no way means that you must learn how to do everything in LaTeX that you could otherwise also do with other technology (e.g., manuscripts in Word, poster presentations in PowerPoint). Learning LaTeX is quite the investment, and it may or may not be worth the time and effort for you.

I self-studied LaTeX when I had plenty of down time during the pandemic because I bought into the hype while getting more into computational cognitive science and thought I needed to learn it. This isn’t to say that I regret my decision—I don’t, because I actually do think that it’s been useful for various reasons, like sharpening my debugging skills—but my time might also have been more productively used elsewhere. I ended up spending hours upon hours poring over Stack Overflow/TeX Exchange and reading docs that I really didn’t need for anything I was trying to do.

In almost every online article describing the supposedly innumerable benefits of LaTeX—however subtly or with as much chagrin as it might be done—you will inevitably hear the argument that one ought to use it because it “looks impressive [on your CV]” or “will make you stand out.” Be that as it may, that should never be your primary motivation.

On TeX forums, you’ll frequently hear people describing why LaTeX is objectively superior to MS Word: how the latter is an ugly, useless, basic software. Frankly, these are usually nothing more than thinly veiled attempts to flex. MS Word is a great technology, and I believe its merits are not mutually exclusive of those of LaTeX.

Ironically, while one might think that proprietary software would stand more starkly in opposition to the spirit of good science, the complexity of open-source LaTeX can also discourage people from trying to learn it. In many ways, LaTeX is just like Vim: for most, it’s at first counterintuitive, hard to pick up, and at the end of the day, also unnecessary for 99.9% of everyday typesetting needs. Of course, that doesn’t stop people from trying to gatekeep…

The dreaded tech bro strikes again.

Under the Hood

The Wonderful World of \(*\)-\(\TeX\)

Hierarchical Schematic

Distributions

(MiKTeX, Tex Live)

↓

Engines

(TeX, pdfTeX, XeTeX, LuaTeX)

↓

Formats

(LaTeX, pdfLaTeX, XeLaTeX, LuaLaTeX)

↓

Packages

(fontspec, geometry, hyperref)

↓

"Commands"

(\chapter, \section, \newcommand{\R}{\mathbb{R}})

*Not exactly a nesting doll relationship; "commands" is used as a non-technical term here.Relational Schematic

LaTeX predates modern document output formats such as Portable Document Format (PDF), which is why it must be converted first from PostScript (the ancestor of PDF) and DeVice Independent (DVI) file formats.

While DVI to PDF has functional limitations, there are also merits to keeping each of these output formats the way they are. DVI to PDF produces a much smaller file size because it compacts the font. Also, DVI to SVG, for example, maintains hyperlinks. PostScript, on the other hand, is optimized for printing.

The Little Engines that Could

LaTeX is compiled using an engine. The act of compilation is called a format (e.g., XeTeX). There are various flavors of TeX each with their own benefits/downsides, but in terms of functionality ordered from least to most powerful, it would be: TeX, pdfTeX, XeTeX, and then LuaTeX.

| Engine (Binary Executable) | Description | Advantages/Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

TeX |

Knuth’s original TeX | Most basic engine, you’re probably never going to use it |

e-TeX |

Added several primitives to TeX | Functionality has been incorporated into newer engines anyway, so need to use it |

pdfTeX |

eTeX plus pdf-relevant primitives | Default engine of contemporary TeX systems |

XeTeX |

eTeX plus some pdfTeX primitives and supports Unicode | Best option for formatting custom fonts |

LuaTeX |

XeTeX plus embedded Lua scripting functionality | Useful if you’re going to script in Lua |

(u)pTeX |

pTeX is for vertically written Japanese, upTeX is a further extension that supports Unicode | Unless, of course, you’re writing in Japanese, you’re not going to use this |

Quick Math

Quick Maths

LaTeX is renowned for its quick, easy, and beautiful formatting of mathematical formulae

Math Mode

Everything in this section will be written in math mode, a set of environments for formatting mathematical formulae. There are three subsets of math mode:

Inline (Default) Math Environment

\begin{math} ... \end{math}\( ... \)$ ... $

Display Math Environment

\begin{displaymath} ... \end{displaymath}\[ ... \]-

$$ ... $$(Not recommended in LaTeX2ε) - \[P(A \mid B) = \frac{P(B \mid A) \, P(A)}{P(B)}\]

Equation Math Environment

\begin{equation} . . . \end{equation}

Operators and Relational Symbols

| Control Sequence | Output | Control Sequence | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

\times |

\(\times\) | \geq |

\(\geq\) |

\cdot |

\(\cdot\) | \leq |

\(\leq\) |

\div |

\(\div\) | \neq |

\(\leq\) |

\pm |

\(\pm\) | \approx |

\(\approx\) |

”+”, “-“, and “/” symbols are not explicitly defined because they can be typed via a standard keyboard without Alt + #### (the four-digit Unicode specifiction) in Windows and option for Mac. That being said, you could technically just use those symbols directly.

Subscript, Superscript, and Fractions

Subscript characters are preceded by _:

- e.g.,

x^3renders as \(x^3\)

Superscript is precded by ^:

- e.g.,

–ONO_2renders as \(–ONO_2\)

Fractions are preceded by \frac and then broken up into numerator and denominator with two groups indicated by braces:

- e.g.,

\frac{3}{x}renders as \(\frac{3}{x}\)

Grouping as a general concept is enabled through braces. If you wanted to apply sub- or superscipt formatting to a group of characters, you would use braces:

- e.g.,

x^{x+1}renders as \(x^{x+1}\) vs.x^x+1renders as \(x^x+1\)

Greek Alphabet

| Control Sequence | Output |

|---|---|

\alpha A |

\(\alpha\) \(A\) |

\beta B |

\(\beta\) \(B\) |

\gamma Gamma |

\(\gamma\) \(\Gamma\) |

\delta Delta |

\(\delta\) \(\Delta\) |

\epsilon E \varepsilon |

\(\epsilon\) \(E\) \(\varepsilon\) |

\zeta Z |

\(\zeta\) \(Z\) |

\eta H |

\(\eta\) \(H\) |

\theta \Theta \vartheta |

\(\theta\) \(\Theta\) \(\vartheta\) |

\iota I |

\(\iota\) \(I\) |

\kappa K |

\(\kappa\) \(K\) |

\lambda \Lambda |

\(\lambda\) \(\Lambda\) |

\mu M |

\(\mu\) \(M\) |

\nu N |

\(\nu\) \(N\) |

\xi \Xi |

\(\xi\) \(\Xi\) |

\o \O |

\(o\) \(O\) |

\pi \Pi |

\(\pi\) \(\Pi\) |

\rho P \varrho |

\(\rho\) \(P\) \(\varrho\) |

\sigma \Sigma |

\(\sigma\) \(\Sigma\) |

\tau T |

\(\tau\) \(T\) |

\upsilon \Upsilon |

\(\upsilon\) \(\Upsilon\) |

\phi \Phi \varphi |

\(\phi\) \(\Phi\) \(\varphi\) |

\chi X |

\(\chi\) \(X\) |

\phi \Psi |

\(\psi\) \(\Psi\) |

\omega \Omega |

\(\omega\) \(\Omega\) |

Note the case-sensitive control sequences. Additionally, not all letter-case combinations are implemented as control sequences (e.g., capital A). This is an exhaustive list, although not all websites or online resources will provide it.

Additional Resources