Intro to Bayesian Regression in R

Welcome! This is an intro-level workshop about Bayesian mixed effects

regression in R. We’ll cover the basics of Bayesian linear and logit

models. You should have an intermediate-level understanding of R and

Frequentist linear regression (using e.g. lm and lmer in R).

Acknowledgments: To make our analyses directly comparable to analyses we’ve already covered, this workshop is directly copied from Allie’s awesome workshop on Frequentist mixed-effect regression. That workshop was adapted from code provided by Gabriela K Hajduk, who in turn referenced a workshop developed by Liam Bailey. Parts of the tutorial are also adapted from a lesson on partial pooling by Tristan Mahr.

For further reading, please check out their tutorials and blogs here:

https://gkhajduk.github.io/2017-03-09-mixed-models/

https://www.tjmahr.com/plotting-partial-pooling-in-mixed-effects-models/

Setup

First, we’ll just get everything set up. We need to tweak some

settings, load packages, and read our data.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

#change some settings

options(contrasts = c("contr.sum","contr.poly"))

#this tweaks makes sure that contrasts are interpretable as main effects

#time to load some packages!

library(lme4) #fit the models

library(lmerTest) #gives p-values and more info

library(car) #more settings for regression output

library(tidyr) #for data wrangling

library(dplyr) #for data wrangling

library(tibble) #for data wrangling

library(ggplot2) #plotting raw data

library(data.table) #for pretty HTML tables of model parameters

library(brms) # bayesian regression!

library(emmeans) # used to get predicted means per condition

library(modelr) # used to get predicted means per condition

library(tidybayes) # for accessing model posteriors

library(bayestestR) # for testing over posteriors

#load the data

dragons <- read.csv("2020-10-21-dragon-data.csv")

Data

Let’s get familiar with our dataset. This is a fictional dataset about dragons. Each dragon has one row. We have information about each dragon’s body length and cognitive test score. Let’s say our first research question is whether the length of the dragon is related to its intelligence.

We also have some other information about each dragon: We know about the mountain range where it lives, its color, its diet, and whether or not it breathes fire.

Let’s take a look at the data and check the counts of our variables:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

# take a peek at the header

head(dragons)

#check out counts for all our categorical variables

table(dragons$mountainRange)

table(dragons$diet)

table(dragons$color)

table(dragons$breathesFire)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

## testScore bodyLength mountainRange color diet breathesFire

## 1 0.0000000 175.5122 Bavarian Blue Carnivore 1

## 2 0.7429138 190.6410 Bavarian Blue Carnivore 1

## 3 2.5018247 169.7088 Bavarian Blue Carnivore 1

## 4 3.3804301 188.8472 Bavarian Blue Carnivore 1

## 5 4.5820954 174.2217 Bavarian Blue Carnivore 0

## 6 12.4536350 183.0819 Bavarian Blue Carnivore 1

##

## Bavarian Central Emmental Julian Ligurian Maritime Sarntal Southern

## 60 60 60 60 60 60 60 60

##

## Carnivore Omnivore Vegetarian

## 156 167 157

##

## Blue Red Yellow

## 160 160 160

##

## 0 1

## 229 251

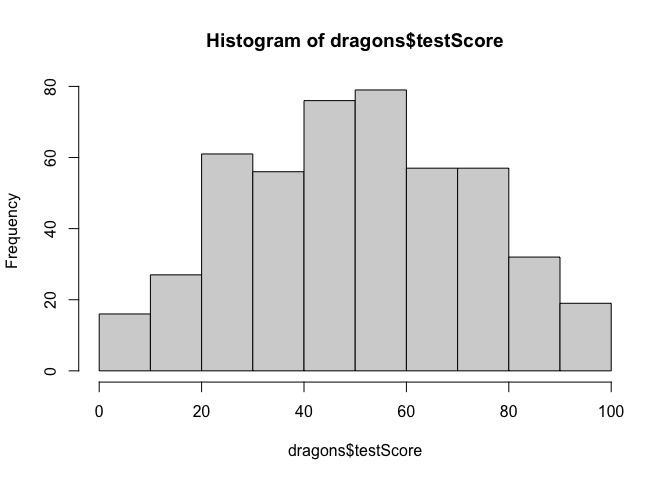

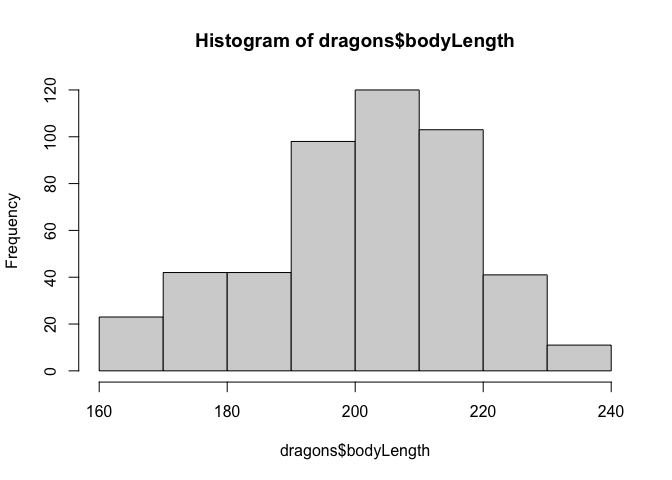

Now let’s check distributions. Do test scores and body length measurements look approximately normal?

1

2

#check assumptions: do our continuous variables have approximately normal distributions?

hist(dragons$testScore)

1

hist(dragons$bodyLength)

Bayesian Linear Regression

Okay, let’s start fitting some lines! Key Question: Does body

length predict test score?

One way to analyse this data would be to try fitting a linear model to all our data, ignoring all the other variables for now. To make sure that we can interpret our coefficients, we should mean-center our continuous measure of body length before using it in a model.

This is a “complete pooling” approach, where we “pool” together all the data and ignore the fact that some observations came from specific mountain ranges.

1

2

model <- lm(testScore ~ scale(bodyLength), data = dragons)

summary(model)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = testScore ~ scale(bodyLength), data = dragons)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -56.962 -16.411 -0.783 15.193 55.200

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 50.3860 0.9676 52.072 <2e-16 ***

## scale(bodyLength) 8.9956 0.9686 9.287 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 21.2 on 478 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.1529, Adjusted R-squared: 0.1511

## F-statistic: 86.25 on 1 and 478 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

Incredible! It’s super significant! We’re gonna publish in Nature

Dragonology! How can we run an analogous Bayesian regression to get full

posterior distributions of our coefficient? Since we standardized body

length, it might be reasonable to set a normal(0, sd(testScore)) prior

over the effect of body length, which says that we expect a unit

increase in body length to yield on the order of somewhere between a

unit decrease and a unit increase in test score. The code is mostly the

same except that we use the brm function instead of lm, we specify a

file to store our model in (so we don’t have to fit it multiple times),

and we specify our normal prior for the model coefficients:

1

2

3

model.bayes <- brm(testScore ~ scale(bodyLength),

data=dragons, file='bodyLength',

prior=set_prior(paste0('normal(0, ', sd(dragons$testScore), ')')))

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

##

## SAMPLING FOR MODEL '49f78aecf53dc588372d55583a8e39cb' NOW (CHAIN 1).

## Chain 1:

## Chain 1: Gradient evaluation took 2.6e-05 seconds

## Chain 1: 1000 transitions using 10 leapfrog steps per transition would take 0.26 seconds.

## Chain 1: Adjust your expectations accordingly!

## Chain 1:

## Chain 1:

## Chain 1: Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1: Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1: Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1: Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1: Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1: Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1: Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1: Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1: Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1: Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1: Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1: Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1:

## Chain 1: Elapsed Time: 0.052493 seconds (Warm-up)

## Chain 1: 0.043537 seconds (Sampling)

## Chain 1: 0.09603 seconds (Total)

## Chain 1:

##

## SAMPLING FOR MODEL '49f78aecf53dc588372d55583a8e39cb' NOW (CHAIN 2).

## Chain 2:

## Chain 2: Gradient evaluation took 1.3e-05 seconds

## Chain 2: 1000 transitions using 10 leapfrog steps per transition would take 0.13 seconds.

## Chain 2: Adjust your expectations accordingly!

## Chain 2:

## Chain 2:

## Chain 2: Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2: Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2: Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2: Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2: Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2: Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2: Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2: Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2: Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2: Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2: Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2: Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2:

## Chain 2: Elapsed Time: 0.064402 seconds (Warm-up)

## Chain 2: 0.035814 seconds (Sampling)

## Chain 2: 0.100216 seconds (Total)

## Chain 2:

##

## SAMPLING FOR MODEL '49f78aecf53dc588372d55583a8e39cb' NOW (CHAIN 3).

## Chain 3:

## Chain 3: Gradient evaluation took 1.2e-05 seconds

## Chain 3: 1000 transitions using 10 leapfrog steps per transition would take 0.12 seconds.

## Chain 3: Adjust your expectations accordingly!

## Chain 3:

## Chain 3:

## Chain 3: Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3: Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3: Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3: Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3: Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3: Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3: Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3: Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3: Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3: Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3: Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3: Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3:

## Chain 3: Elapsed Time: 0.058688 seconds (Warm-up)

## Chain 3: 0.038065 seconds (Sampling)

## Chain 3: 0.096753 seconds (Total)

## Chain 3:

##

## SAMPLING FOR MODEL '49f78aecf53dc588372d55583a8e39cb' NOW (CHAIN 4).

## Chain 4:

## Chain 4: Gradient evaluation took 1.3e-05 seconds

## Chain 4: 1000 transitions using 10 leapfrog steps per transition would take 0.13 seconds.

## Chain 4: Adjust your expectations accordingly!

## Chain 4:

## Chain 4:

## Chain 4: Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4: Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4: Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4: Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4: Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4: Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4: Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4: Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4: Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4: Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4: Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4: Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4:

## Chain 4: Elapsed Time: 0.052508 seconds (Warm-up)

## Chain 4: 0.041537 seconds (Sampling)

## Chain 4: 0.094045 seconds (Total)

## Chain 4:

1

summary(model.bayes, prior=TRUE)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

## Family: gaussian

## Links: mu = identity; sigma = identity

## Formula: testScore ~ scale(bodyLength)

## Data: dragons (Number of observations: 480)

## Samples: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

## total post-warmup samples = 4000

##

## Priors:

## b ~ normal(0, 23.0088071104418)

## Intercept ~ student_t(3, 51, 26.1)

## sigma ~ student_t(3, 0, 26.1)

##

## Population-Level Effects:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## Intercept 50.37 0.98 48.46 52.22 1.00 3608 2184

## scalebodyLength 8.98 0.95 7.14 10.86 1.00 3939 3218

##

## Family Specific Parameters:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## sigma 21.25 0.67 19.96 22.59 1.00 3826 3030

##

## Samples were drawn using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

## and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

## scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).

After waiting a minute for the model to compile and fit, we can see that

this summary gives us a little more information than lm did. First, it

tells us some basics about our model: the noise distribution family is

Gaussian with an identity link function, and so on. Next it tells us

what our priors are. In this case, brms uses default Student t priors

for the intercept and for the standard deviation, and our specified

normal prior for the regression slope. Finally, brms tells us about

our results. Here Estimate is the posterior mean (which is the most

likely for unimodal/symmetric distributions), Est.Error is the

standard deviation of the posterior (kind of like the standard error),

and l-95% CI and u-95% CI are the credible intervals (values inside

this range are the 95% most probable values). We also get some

convergence information for each parameter (Rhat, Bulk_ESS, and

Tail_ESS), which we’ll talk about later.

You also might be wondering what the heck is the deal with all those

chain outputs. Those are just updates on the algorithm brms uses to

compute the posterior. It’s called Markov-Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC)

sampling and you can learn more about it

here

if you’re interested.

To perform significance testing on our Bayesian regression model, we can

use the nifty describe_posterior function from the bayestestR

package, which computes a bunch of different tests for us:

1

2

describe_posterior(model.bayes, ci=.95, rope_ci=.95,

test=c('pd', 'p_map', 'rope', 'bf'))

1

2

3

4

5

6

## # Description of Posterior Distributions

##

## Parameter | Median | 95% CI | p_MAP | pd | 95% ROPE | % in ROPE | BF | Rhat | ESS

## --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

## Intercept | 50.384 | [48.511, 52.268] | 0 | 100.00% | [-2.301, 2.301] | 0 | 6.641e+52 | 1.000 | 3539.342

## scalebodyLength | 8.971 | [ 7.218, 10.889] | 0 | 100.00% | [-2.301, 2.301] | 0 | 1.316e+06 | 1.000 | 3922.522

Like before, this gives us summaries of our posterior (in this case the

median and 95% CI). But this time we also see two measures of effect

existence, analogous to p-values on Frequentist approaches. p_MAP is

the posterior density at 0 divided by the posterior density at the mode,

and is on the same scale as a p-value. pd is the probability of

direction, which is the percentage of the posterior that all has the

same sign (whichever is greater). We also get two measures of effect

significance: the % in ROPE tells us how much of the posterior is

inside a null region (in this case a standardized effect size of <

.1), and BF is a Bayes Factor, where BF > 1 indicates support for

the alternative hypothesis and BF < 1 indicates support for the null

hypothesis. There is a whole lot of discussion about which of these

metrics are best to use, and we could take a whole meeting talking about

this. But for now, we can take solace that all of the measures agree-

just like we saw before, it looks like the effect of body length is

significant!

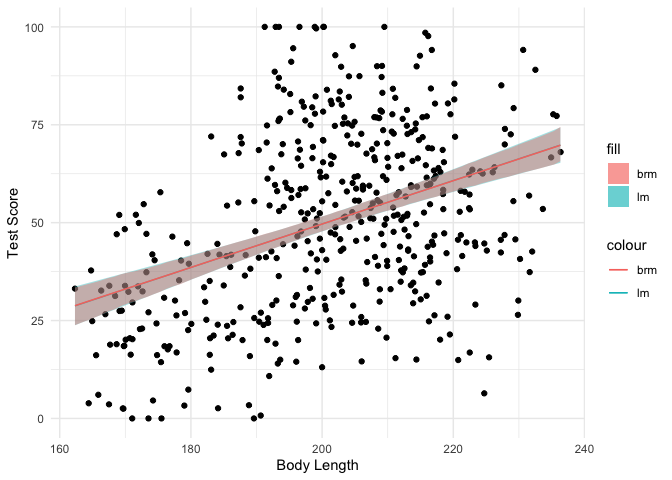

We saw that the estimates and inferences from both models look similar,

but let’s plot the data with ggplot2 to see how much they actually

overlap.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

lm.emm <- emmeans(model, ~bodyLength,

at=list(bodyLength=seq(min(dragons$bodyLength),

max(dragons$bodyLength)))) %>%

as.data.frame

brm.emm <- emmeans(model.bayes, ~bodyLength,

at=list(bodyLength=seq(min(dragons$bodyLength),

max(dragons$bodyLength)))) %>%

as.data.frame

ggplot(dragons, aes(x=bodyLength, y=testScore)) +

geom_point() +

geom_line(aes(y=emmean, color='lm'), data=lm.emm) +

geom_ribbon(aes(y=emmean, ymin=lower.CL, ymax=upper.CL, fill='lm'),

data=lm.emm, alpha=0.4) +

geom_line(aes(y=emmean, color='brm'), data=brm.emm) +

geom_ribbon(aes(y=emmean, ymin=lower.HPD, ymax=upper.HPD, fill='brm'),

data=brm.emm, alpha=0.4) +

xlab("Body Length") +

ylab("Test Score") + theme_minimal()

As you can see, the fitted lines and 95% CIs look almost exactly the same between the two different approaches. Then why bother waiting for a Bayesian model to fit? Because instead of just an estimate and a confidence interval, we get a full posterior distribution over our model coefficients that allows us to directly infer the most probable values:

1

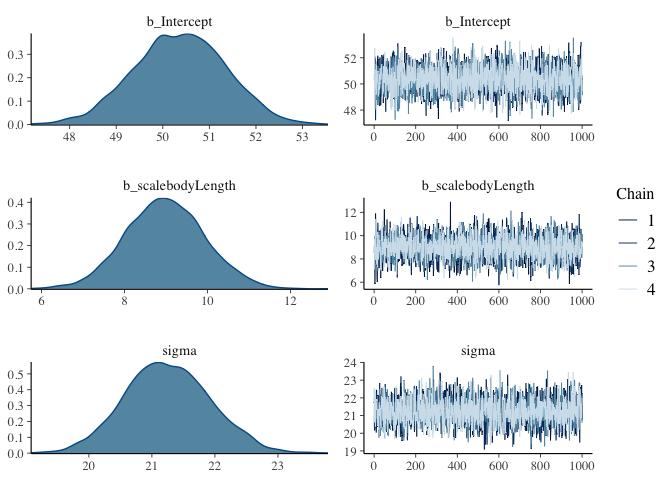

plot(model.bayes)

From these plots, we can see that the average test score is most likely about 50, but could also be somewhere between 48 and 53. Similarly, we can see that a unit increase in body length is most likely to yield an increase in 9 points of test score, and that the standard deviation in test scores is probably around 21 test points. With our Frequentist regression, we can predict that these values make the observed data most likely, but we can’t directly make inferences about how probable the values are.

Then what are the squiggly things on the right side? Since most

regression models don’t have easy analytic solutions, we have to sample

from our posterior distribution instead of calculating it directly. The

lines are called MCMC chains, the x-axis is the number of each sample

and the y-axis is the value of each sample. For now, all you need to

know is that if the chains look like nice fuzzy caterpillars (like they

do here), then our model has converged. Otherwise, brms will give us

some warnings that things went awry, and will give us advice for how to

solve the problem.

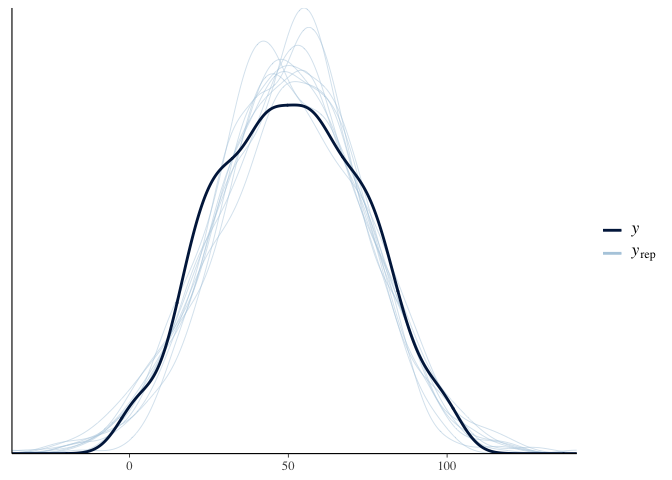

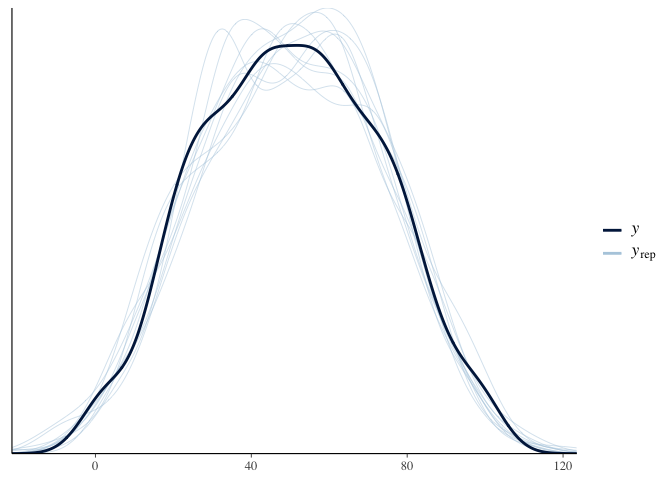

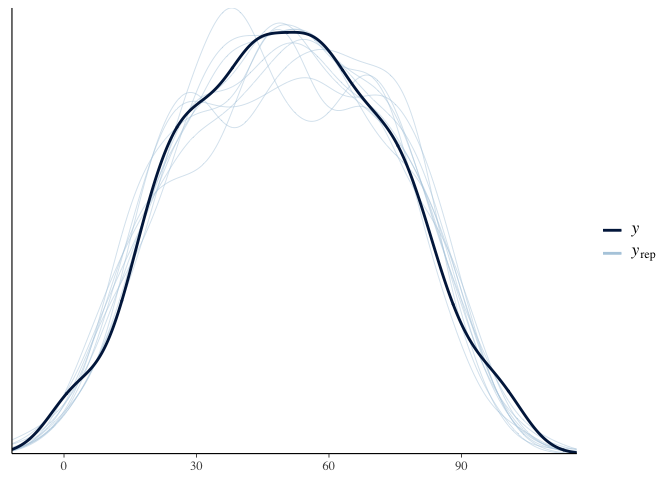

Another benefit of brms is that we can use it to simulate test scores

and see how well it covers the actual distribution of test scores. This

is called a “posterior predictive check.” Here the dark line is the

actual distribution of test scores, and each light line is the

distribution of test scores predicted by a single sample of the

posterior. Since the light lines mostly cover the solid line, it looks

like our model fits the data fairly well:

1

pp_check(model.bayes)

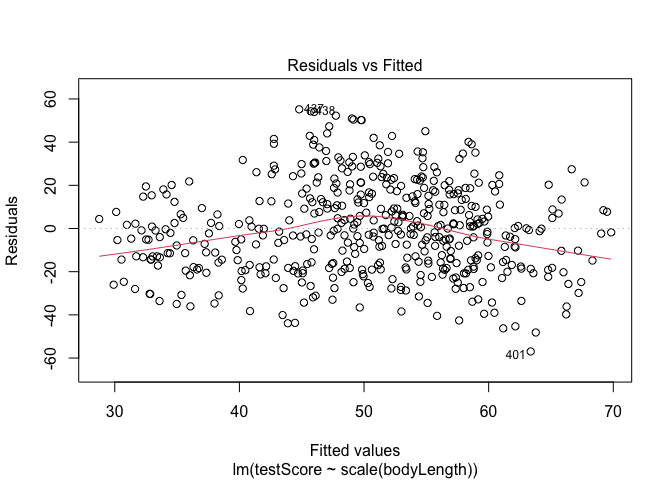

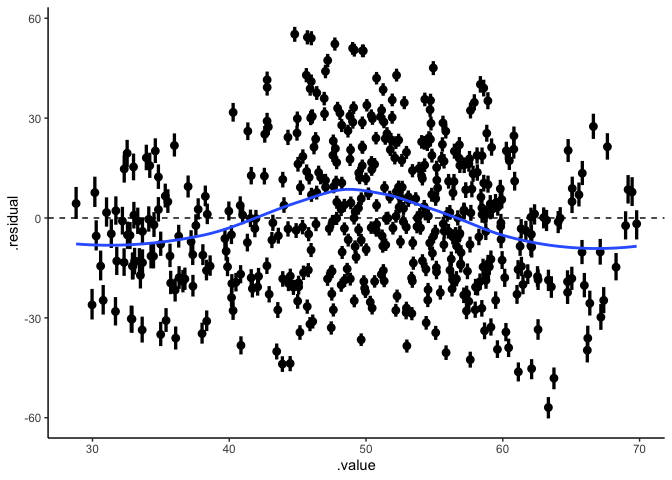

But before we make any grand conclusions, we need to check that we met

assumptions! We can use plot for the Frequentist lm model. To check

the assumptions of the Bayesian model, we can use add_residual_draws

from the tidybayes package to get the residual posterior for each data

point.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

draws <- full_join(add_fitted_draws(dragons, model.bayes),

add_residual_draws(dragons, model.bayes)) %>%

group_by(.row) %>%

median_hdi(.value, .residual)

## Let's plot the residuals from this model. Ideally, the red line should be flat.

plot(model, which = 1) # not perfect, but looks alright

1

2

3

4

5

6

ggplot(draws, aes(x=.value, xmin=.value.lower, xmax=.value.upper,

y=.residual, ymin=.residual.lower, ymax=.residual.upper)) +

geom_pointinterval() +

geom_hline(yintercept=0, linetype='dashed') +

stat_smooth(se=FALSE) +

theme_classic()

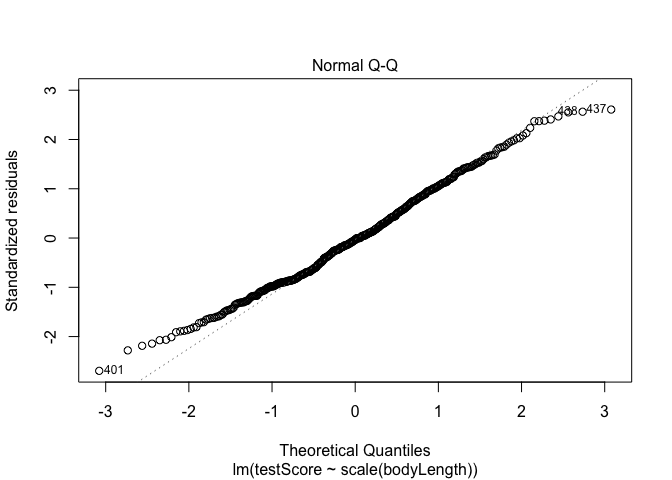

1

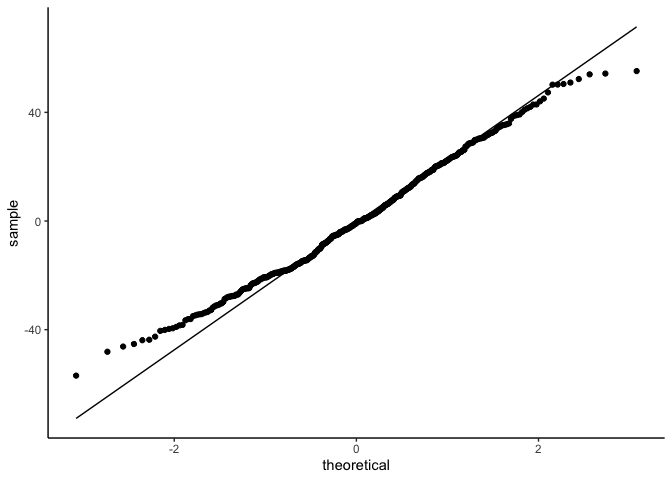

2

## Have a quick look at the qqplot too - point should ideally fall onto the diagonal dashed line

plot(model, which = 2) # a bit off at the extremes, but that's often the case; again doesn't look too bad

1

2

3

4

ggplot(draws, aes(sample=.residual)) +

geom_qq() +

geom_qq_line() +

theme_classic()

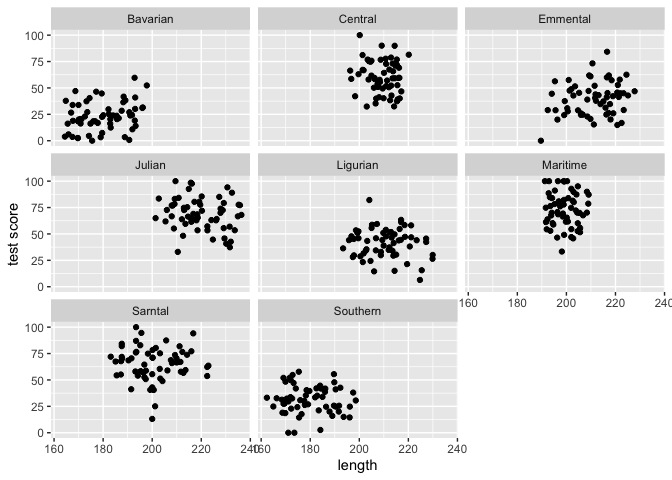

But linear models also assume that observations are INDEPENDENT. Uh oh.

We collected multiple samples from eight mountain ranges. It’s perfectly plausible that the data from within each mountain range are more similar to each other than the data from different mountain ranges - they are correlated. This could be a problem.

1

2

3

4

5

6

#Lets have a quick look at the data split by mountain range

#We use the facet_wrap to do that

ggplot(data = dragons, aes(x = bodyLength, y = testScore)) +

geom_point() +

facet_wrap(.~mountainRange) +

xlab("length") + ylab("test score")

From the above plots it indeed looks like our mountain ranges vary both in the dragon body length and in their test scores. This confirms that our observations from within each of the ranges aren’t independent. We can’t ignore that.

Bayesian Multilevel Linear Regression

Mountain range clearly introduces a structured source of variance

in our data. We need to control for that variation if we want to

understand whether body length really predicts test scores.

Multilevel regression is a compromise: Partial pooling! We can let each mountain range have its own regression line, but make an informed guess about that line based on the group-level estimates. This is especially useful when some groups/participants have incomplete data.

Note that here we use the term “multilevel” or “hierarchical” instead of “mixed effect” regression. This is because in a Bayesian framework, all of your effects are modeled as “random” effects! In Frequentist regression, “random” effects are just normal effects that are modeled with an underlying standard normal distribution: in other words, they’re modeled with a standard normal prior. Since all effects in Bayesian regressions have priors, it’s easier and more precise to refer to population-level effects (akin to “fixed” effects) and group-level effects (akin to “random” effects).

Should Mountain Range be a Population-level or Group-level effect?

Since we want to estimate the mean effect of body-length over all mountain ranges, we want a population-level effect of body length. But since we also think that mountain ranges could have different mean test scores and different effects of body length, we also want separate group-level effects over mountain ranges.

Here’s how we did this with lmer:

1

2

3

4

5

#let's fit our first multilevel model!

multilevel_model <- lmer(testScore ~ scale(bodyLength) + (1+scale(bodyLength)|mountainRange), data = dragons)

#what's the verdict?

summary(multilevel_model)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

## Linear mixed model fit by REML. t-tests use Satterthwaite's method [

## lmerModLmerTest]

## Formula:

## testScore ~ scale(bodyLength) + (1 + scale(bodyLength) | mountainRange)

## Data: dragons

##

## REML criterion at convergence: 3980.5

##

## Scaled residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -3.5004 -0.6683 0.0207 0.6592 2.9449

##

## Random effects:

## Groups Name Variance Std.Dev. Corr

## mountainRange (Intercept) 324.102 18.003

## scale(bodyLength) 9.905 3.147 -1.00

## Residual 221.578 14.885

## Number of obs: 480, groups: mountainRange, 8

##

## Fixed effects:

## Estimate Std. Error df t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 51.75302 6.40349 6.91037 8.082 9.16e-05 ***

## scale(bodyLength) -0.03326 1.68317 10.22337 -0.020 0.985

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Correlation of Fixed Effects:

## (Intr)

## scl(bdyLng) -0.674

## optimizer (nloptwrap) convergence code: 0 (OK)

## boundary (singular) fit: see ?isSingular

Again, the Bayesian version with brms is essentially the same to run:

1

2

3

4

5

6

#let's fit our first mixed model!

multilevel_model.bayes <- brm(testScore ~ scale(bodyLength) + (1+scale(bodyLength)|mountainRange),

data=dragons, file='bodyLength_multilevel',

prior=set_prior(paste0('normal(0, ', sd(dragons$testScore), ')')))

summary(multilevel_model.bayes, prior=TRUE)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

## Family: gaussian

## Links: mu = identity; sigma = identity

## Formula: testScore ~ scale(bodyLength) + (1 + scale(bodyLength) | mountainRange)

## Data: dragons (Number of observations: 480)

## Samples: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

## total post-warmup samples = 4000

##

## Priors:

## b ~ normal(0, 23.0088071104418)

## Intercept ~ student_t(3, 51, 26.1)

## L ~ lkj_corr_cholesky(1)

## sd ~ student_t(3, 0, 26.1)

## sigma ~ student_t(3, 0, 26.1)

##

## Group-Level Effects:

## ~mountainRange (Number of levels: 8)

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat

## sd(Intercept) 20.63 5.92 12.19 35.13 1.00

## sd(scalebodyLength) 3.76 2.17 0.35 8.89 1.00

## cor(Intercept,scalebodyLength) -0.55 0.39 -0.98 0.45 1.00

## Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## sd(Intercept) 1362 1915

## sd(scalebodyLength) 1820 1699

## cor(Intercept,scalebodyLength) 3176 2620

##

## Population-Level Effects:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## Intercept 51.25 7.11 36.62 64.88 1.00 1040 1590

## scalebodyLength 0.12 1.97 -3.97 3.91 1.00 2340 1936

##

## Family Specific Parameters:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## sigma 14.93 0.49 14.03 15.93 1.00 4904 2967

##

## Samples were drawn using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

## and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

## scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).

1

2

describe_posterior(multilevel_model.bayes, ci=.95, rope_ci=.95,

test=c('pd', 'p_map', 'rope', 'bf'))

1

2

3

4

5

6

## # Description of Posterior Distributions

##

## Parameter | Median | 95% CI | p_MAP | pd | 95% ROPE | % in ROPE | BF | Rhat | ESS

## --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

## Intercept | 51.279 | [36.597, 64.809] | 0.000 | 100.00% | [-2.301, 2.301] | 0.000 | 91530.079 | 1.000 | 1018.165

## scalebodyLength | 0.200 | [-3.993, 3.871] | 0.979 | 54.57% | [-2.301, 2.301] | 82.163 | 0.078 | 1.000 | 2210.472

1

pp_check(multilevel_model.bayes)

The summary output for brms is pretty much the same as before,

except now we also have a section for group-level effects in addition to

our earlier section for Population-level effects. Since we estimated

separate intercepts and effects of body length on test score for each

mountain range, our model tells us the standard deviation of each of

those two effects, and also the correlation between them. The standard

deviations look fairly similar to the lmer values, but the correlation

looks much more reasonable than the lmer value (i.e., it’s no longer a

perfect negative correlation).

Overall, it looks like when we account for the effect of mountain range, there is no relationship between body length and test scores. This is true for both the Frequentist and the Bayesian regressions. Well, so much for our Nature Dragonology paper!

Unless… What about our other variables? Let’s test whether diet is related to test scores instead.

1

2

3

4

5

model.diet <- brm(testScore ~ diet + (1+diet|mountainRange),

data=dragons, file='diet_multilevel',

prior=set_prior(paste0('normal(0, ', sd(dragons$testScore), ')')))

summary(model.diet, prior=TRUE)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

## Family: gaussian

## Links: mu = identity; sigma = identity

## Formula: testScore ~ diet + (1 + diet | mountainRange)

## Data: dragons (Number of observations: 480)

## Samples: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

## total post-warmup samples = 4000

##

## Priors:

## b ~ normal(0, 23.0088071104418)

## Intercept ~ student_t(3, 51, 26.1)

## L ~ lkj_corr_cholesky(1)

## sd ~ student_t(3, 0, 26.1)

## sigma ~ student_t(3, 0, 26.1)

##

## Group-Level Effects:

## ~mountainRange (Number of levels: 8)

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS

## sd(Intercept) 11.47 3.82 6.57 20.22 1.00 1311

## sd(diet1) 2.70 1.98 0.14 7.47 1.00 935

## sd(diet2) 4.92 2.01 1.85 9.86 1.00 1475

## cor(Intercept,diet1) 0.08 0.44 -0.79 0.83 1.00 3302

## cor(Intercept,diet2) 0.72 0.24 0.10 0.98 1.00 1950

## cor(diet1,diet2) -0.29 0.43 -0.90 0.69 1.00 2261

## Tail_ESS

## sd(Intercept) 1923

## sd(diet1) 1867

## sd(diet2) 1961

## cor(Intercept,diet1) 2301

## cor(Intercept,diet2) 2866

## cor(diet1,diet2) 2887

##

## Population-Level Effects:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## Intercept 49.45 4.16 41.08 57.96 1.00 1168 1650

## diet1 -15.02 1.61 -18.09 -11.41 1.00 2308 1715

## diet2 15.00 2.13 10.57 18.89 1.00 1653 1758

##

## Family Specific Parameters:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## sigma 10.74 0.35 10.05 11.46 1.00 4776 2879

##

## Samples were drawn using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

## and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

## scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).

1

2

describe_posterior(model.diet, ci=.95, rope_ci=.95,

test=c('pd', 'p_map', 'rope', 'bf'))

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

## # Description of Posterior Distributions

##

## Parameter | Median | 95% CI | p_MAP | pd | 95% ROPE | % in ROPE | BF | Rhat | ESS

## -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

## Intercept | 49.455 | [ 40.919, 57.793] | 0 | 100.00% | [-2.301, 2.301] | 0 | 9.108e+08 | 1.001 | 1161.725

## diet1 | -15.090 | [-18.170, -11.587] | 0 | 100.00% | [-2.301, 2.301] | 0 | 2381.239 | 1.001 | 2050.769

## diet2 | 15.072 | [ 10.533, 18.810] | 0 | 100.00% | [-2.301, 2.301] | 0 | 2135.790 | 1.001 | 1639.868

1

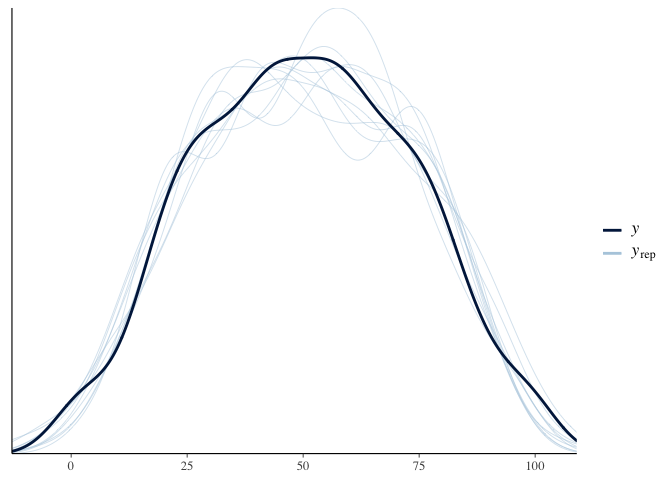

pp_check(model.diet)

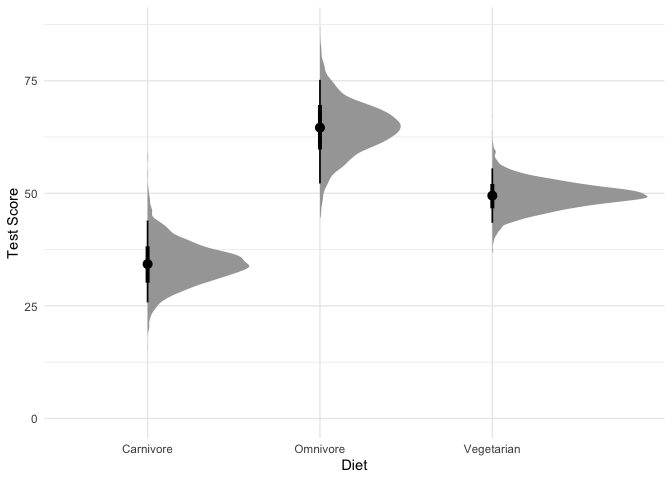

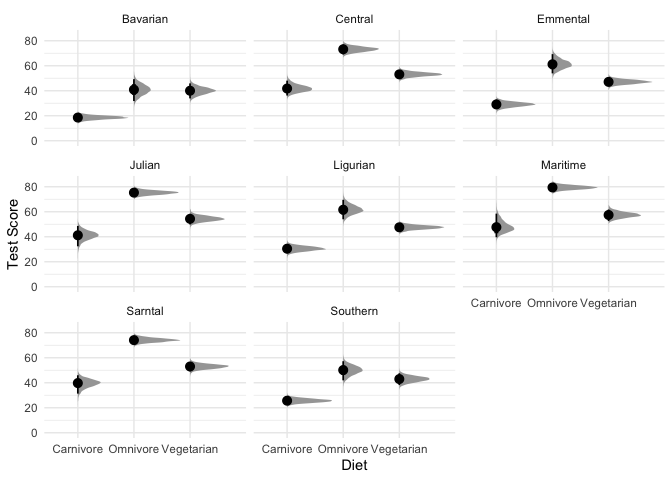

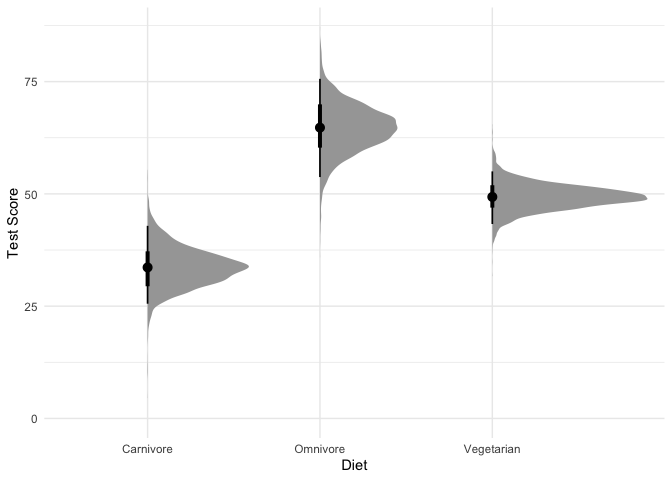

Visualizing the effect of diet on test scores predicted by our model will help us better understand what we just found:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

#Plot average test score by diet type

dragons %>%

data_grid(diet) %>%

add_fitted_draws(model.diet, re_formula=NA) %>%

ggplot(aes(x=diet, y=.value)) +

stat_halfeye(point_interval=median_hdi) + ylim(0, NA) +

xlab("Diet") + ylab("Test Score") +

theme_minimal()

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

#Let's also look at the effect across mountain ranges.

dragons %>%

data_grid(diet, mountainRange) %>%

add_fitted_draws(model.diet) %>%

ggplot(aes(x=diet, y=.value)) +

stat_halfeye(point_interval=median_hdi) + ylim(0, NA) +

facet_wrap( ~ mountainRange) +

xlab("Diet") + ylab("Test Score") +

theme_minimal()

What are we looking at here? The black points represent the mode of the posterior, the thick black lines represent the 66% credible intervals, and the thinner black lines represnt the 95% credible intervals (also called highest density intervals). The curves in gray represent the full posterior distribution. A nice thing about using a Bayesian model is that instead of being stuck with ugly & often misleading bar charts, we can directly plot how likely each mean is along with the full posterior distribution.

In sum, these results look pretty consistent, but there’s clearly still variability among different mountains.

So far, so good. But what if we’re interested in testing multiple variables at the same time? We build a model with an interaction term!

1

2

3

4

5

model.diet.length <- brm(testScore ~ diet*scale(bodyLength) + (1 + diet*scale(bodyLength)|mountainRange),

data=dragons, file='diet_length',

prior=set_prior(paste0('normal(0, ', sd(dragons$testScore), ')')))

summary(model.diet.length, prior=TRUE)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

## Family: gaussian

## Links: mu = identity; sigma = identity

## Formula: testScore ~ diet * scale(bodyLength) + (1 + diet * scale(bodyLength) | mountainRange)

## Data: dragons (Number of observations: 480)

## Samples: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

## total post-warmup samples = 4000

##

## Priors:

## b ~ normal(0, 23.0088071104418)

## Intercept ~ student_t(3, 51, 26.1)

## L ~ lkj_corr_cholesky(1)

## sd ~ student_t(3, 0, 26.1)

## sigma ~ student_t(3, 0, 26.1)

##

## Group-Level Effects:

## ~mountainRange (Number of levels: 8)

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI

## sd(Intercept) 11.52 4.04 6.30

## sd(diet1) 2.79 2.01 0.19

## sd(diet2) 3.33 2.07 0.31

## sd(scalebodyLength) 1.89 1.42 0.07

## sd(diet1:scalebodyLength) 1.68 1.55 0.05

## sd(diet2:scalebodyLength) 2.00 1.59 0.07

## cor(Intercept,diet1) 0.09 0.35 -0.60

## cor(Intercept,diet2) 0.37 0.34 -0.39

## cor(diet1,diet2) -0.14 0.37 -0.77

## cor(Intercept,scalebodyLength) -0.14 0.36 -0.76

## cor(diet1,scalebodyLength) 0.02 0.38 -0.71

## cor(diet2,scalebodyLength) -0.11 0.38 -0.75

## cor(Intercept,diet1:scalebodyLength) -0.01 0.38 -0.74

## cor(diet1,diet1:scalebodyLength) 0.05 0.38 -0.69

## cor(diet2,diet1:scalebodyLength) -0.06 0.37 -0.74

## cor(scalebodyLength,diet1:scalebodyLength) 0.03 0.37 -0.67

## cor(Intercept,diet2:scalebodyLength) -0.15 0.38 -0.79

## cor(diet1,diet2:scalebodyLength) 0.03 0.38 -0.70

## cor(diet2,diet2:scalebodyLength) -0.15 0.37 -0.79

## cor(scalebodyLength,diet2:scalebodyLength) 0.04 0.38 -0.68

## cor(diet1:scalebodyLength,diet2:scalebodyLength) -0.02 0.38 -0.72

## u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS

## sd(Intercept) 21.36 1.00 1599

## sd(diet1) 7.89 1.00 1650

## sd(diet2) 8.22 1.00 1506

## sd(scalebodyLength) 5.32 1.00 2439

## sd(diet1:scalebodyLength) 5.78 1.00 2221

## sd(diet2:scalebodyLength) 5.98 1.00 2163

## cor(Intercept,diet1) 0.75 1.00 5263

## cor(Intercept,diet2) 0.88 1.00 4551

## cor(diet1,diet2) 0.62 1.00 3261

## cor(Intercept,scalebodyLength) 0.59 1.00 5336

## cor(diet1,scalebodyLength) 0.72 1.00 4651

## cor(diet2,scalebodyLength) 0.66 1.00 3869

## cor(Intercept,diet1:scalebodyLength) 0.70 1.00 6345

## cor(diet1,diet1:scalebodyLength) 0.74 1.00 4627

## cor(diet2,diet1:scalebodyLength) 0.65 1.00 4318

## cor(scalebodyLength,diet1:scalebodyLength) 0.71 1.00 3501

## cor(Intercept,diet2:scalebodyLength) 0.60 1.00 5048

## cor(diet1,diet2:scalebodyLength) 0.73 1.00 4024

## cor(diet2,diet2:scalebodyLength) 0.61 1.00 4521

## cor(scalebodyLength,diet2:scalebodyLength) 0.74 1.00 3584

## cor(diet1:scalebodyLength,diet2:scalebodyLength) 0.70 1.00 2956

## Tail_ESS

## sd(Intercept) 1698

## sd(diet1) 2254

## sd(diet2) 1850

## sd(scalebodyLength) 2350

## sd(diet1:scalebodyLength) 2538

## sd(diet2:scalebodyLength) 1896

## cor(Intercept,diet1) 2858

## cor(Intercept,diet2) 3480

## cor(diet1,diet2) 3377

## cor(Intercept,scalebodyLength) 2747

## cor(diet1,scalebodyLength) 3037

## cor(diet2,scalebodyLength) 3611

## cor(Intercept,diet1:scalebodyLength) 2775

## cor(diet1,diet1:scalebodyLength) 3029

## cor(diet2,diet1:scalebodyLength) 2766

## cor(scalebodyLength,diet1:scalebodyLength) 3280

## cor(Intercept,diet2:scalebodyLength) 3217

## cor(diet1,diet2:scalebodyLength) 2959

## cor(diet2,diet2:scalebodyLength) 3098

## cor(scalebodyLength,diet2:scalebodyLength) 3590

## cor(diet1:scalebodyLength,diet2:scalebodyLength) 3481

##

## Population-Level Effects:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS

## Intercept 50.01 4.35 41.32 58.68 1.00 1159

## diet1 -15.06 1.72 -18.34 -11.23 1.00 2522

## diet2 15.50 1.82 11.66 18.86 1.00 2537

## scalebodyLength -0.23 1.30 -2.80 2.42 1.00 4099

## diet1:scalebodyLength -0.56 1.55 -3.54 2.50 1.00 2753

## diet2:scalebodyLength 1.73 1.53 -1.48 4.68 1.00 2898

## Tail_ESS

## Intercept 1220

## diet1 2243

## diet2 2100

## scalebodyLength 2824

## diet1:scalebodyLength 2250

## diet2:scalebodyLength 2588

##

## Family Specific Parameters:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## sigma 10.78 0.35 10.11 11.48 1.00 6093 2712

##

## Samples were drawn using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

## and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

## scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).

1

2

describe_posterior(model.diet.length, ci=.95, rope_ci=.95,

test=c('pd', 'p_map', 'rope', 'bf'))

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

## # Description of Posterior Distributions

##

## Parameter | Median | 95% CI | p_MAP | pd | 95% ROPE | % in ROPE | BF | Rhat | ESS

## -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

## Intercept | 49.960 | [ 40.958, 58.301] | 0.000 | 100.00% | [-2.301, 2.301] | 0.000 | 3.204e+06 | 1.004 | 1064.403

## diet1 | -15.133 | [-18.368, -11.330] | 0.000 | 100.00% | [-2.301, 2.301] | 0.000 | 15268.750 | 1.000 | 2357.941

## diet2 | 15.593 | [ 11.707, 18.894] | 0.000 | 100.00% | [-2.301, 2.301] | 0.000 | 28342.766 | 1.002 | 2425.588

## scalebodyLength | -0.240 | [ -3.000, 2.199] | 0.973 | 57.83% | [-2.301, 2.301] | 96.212 | 0.054 | 1.000 | 4010.814

## diet1.scalebodyLength | -0.607 | [ -3.375, 2.650] | 0.845 | 66.72% | [-2.301, 2.301] | 89.766 | 0.069 | 1.000 | 2464.699

## diet2.scalebodyLength | 1.739 | [ -1.383, 4.732] | 0.418 | 87.30% | [-2.301, 2.301] | 65.588 | 0.140 | 1.000 | 2818.100

1

pp_check(model.diet.length)

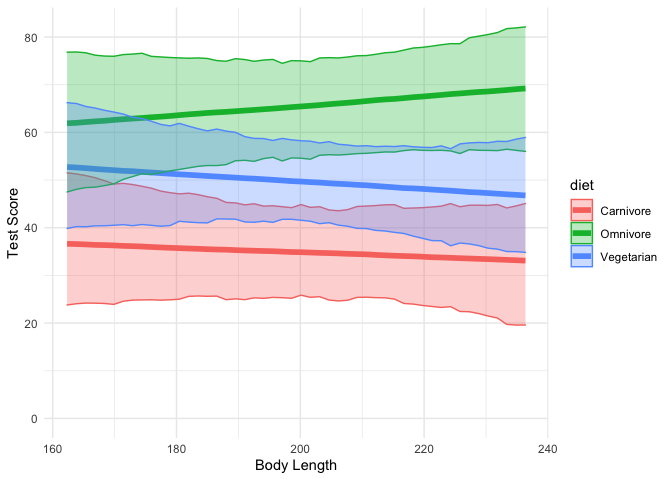

Since the BFs for diet are > 10, it looks like the effect of diet is still significant after we control for body length. We can also see that there seems to be no main effect of body length or interactions between diet and body length, since their corresponding BFs are < .14.

Let’s plot the output again:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

dragons %>%

data_grid(diet, bodyLength=seq_range(bodyLength, 50)) %>%

add_fitted_draws(model.diet.length, re_formula=NA) %>%

median_hdi() %>%

ggplot(aes(x=bodyLength, y=.value, color=diet, fill=diet)) +

geom_line(size=2) +

geom_ribbon(aes(ymin=.lower, ymax=.upper), alpha=0.3) +

ylim(0, NA) +

xlab("Body Length") + ylab("Test Score") +

theme_minimal()

Here we can see that indeed, the effect of body length seems to be close to zero for all three diet types.

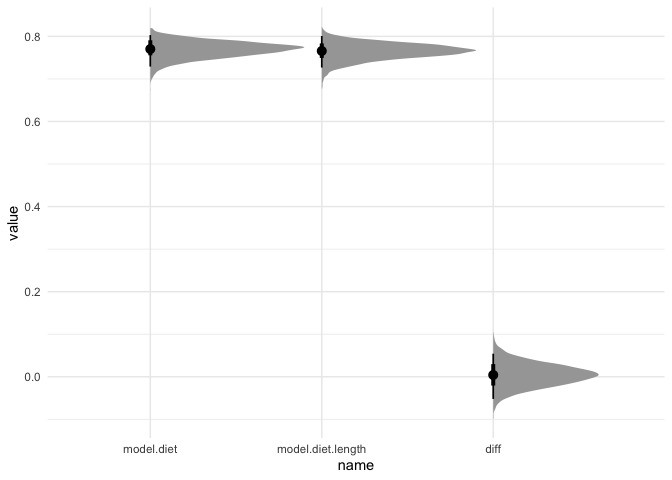

Hmm…. did adding body length to our model make it better? Since we’re Bayesian statisticians, we can compare distributions of adjusted R2 values for each model to answer this question:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

R2 <- data.frame(model.diet=loo_R2(model.diet, summary=FALSE)[,1],

model.diet.length=loo_R2(model.diet.length, summary=FALSE)[,1]) %>%

mutate(diff=model.diet - model.diet.length) %>%

pivot_longer(model.diet:diff) %>%

mutate(name=factor(name, levels=c('model.diet', 'model.diet.length', 'diff')))

ggplot(R2, aes(x=name, y=value)) +

stat_halfeye(point_interval=median_hdi) +

theme_minimal()

As we can see, both models have an R2 of about 0.75, so adding body length doesn’t seem to help. We can also test their difference using LOO-IC:

1

loo(model.diet, model.diet.length)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

## Output of model 'model.diet':

##

## Computed from 4000 by 480 log-likelihood matrix

##

## Estimate SE

## elpd_loo -1832.9 21.6

## p_loo 24.4 4.0

## looic 3665.9 43.2

## ------

## Monte Carlo SE of elpd_loo is NA.

##

## Pareto k diagnostic values:

## Count Pct. Min. n_eff

## (-Inf, 0.5] (good) 474 98.8% 1097

## (0.5, 0.7] (ok) 4 0.8% 230

## (0.7, 1] (bad) 2 0.4% 87

## (1, Inf) (very bad) 0 0.0% <NA>

## See help('pareto-k-diagnostic') for details.

##

## Output of model 'model.diet.length':

##

## Computed from 4000 by 480 log-likelihood matrix

##

## Estimate SE

## elpd_loo -1838.1 21.4

## p_loo 30.4 4.1

## looic 3676.2 42.7

## ------

## Monte Carlo SE of elpd_loo is NA.

##

## Pareto k diagnostic values:

## Count Pct. Min. n_eff

## (-Inf, 0.5] (good) 474 98.8% 1005

## (0.5, 0.7] (ok) 5 1.0% 365

## (0.7, 1] (bad) 1 0.2% 140

## (1, Inf) (very bad) 0 0.0% <NA>

## See help('pareto-k-diagnostic') for details.

##

## Model comparisons:

## elpd_diff se_diff

## model.diet 0.0 0.0

## model.diet.length -5.1 1.8

Again we see that the model without diet does just as well, if not slightly better than, the model with both diet and body length.

Your turn! Try modifying the model above to test whether color is related to testScore, and whether color interacts with diet or bodyLength.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

#Build your model here

#View the output of the model here

#Plot your results below:

Bayesian Multilevel Logistic Regression

Okay, let’s test a new question. Test scores are boring. I actually want to know about which dragons breathe fire. This has way more important practical implications, and is more likely to get me grant funding.

Good news: we have data on fire breathing!

Bad news: It’s a binary variable, so we need to change our model.

With lmer, you need to switch over to the glmer function to gain

access to bernoulli models. But in brms, you just need to specify the

proper noise distribution family:

1

2

3

4

5

logit_model <- brm(breathesFire ~ color + (1+color|mountainRange),

data=dragons, file='fire', family=bernoulli,

prior=prior(normal(0, 2)))

summary(logit_model, prior=TRUE)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

## Family: bernoulli

## Links: mu = logit

## Formula: breathesFire ~ color + (1 + color | mountainRange)

## Data: dragons (Number of observations: 480)

## Samples: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

## total post-warmup samples = 4000

##

## Priors:

## b ~ normal(0, 2)

## Intercept ~ student_t(3, 0, 2.5)

## L ~ lkj_corr_cholesky(1)

## sd ~ student_t(3, 0, 2.5)

##

## Group-Level Effects:

## ~mountainRange (Number of levels: 8)

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS

## sd(Intercept) 0.40 0.27 0.03 1.04 1.00 1346

## sd(color1) 0.35 0.28 0.01 1.04 1.00 1597

## sd(color2) 1.03 0.45 0.39 2.13 1.00 1367

## cor(Intercept,color1) -0.23 0.48 -0.94 0.77 1.00 2969

## cor(Intercept,color2) 0.15 0.44 -0.72 0.88 1.00 1228

## cor(color1,color2) -0.07 0.49 -0.88 0.84 1.00 1132

## Tail_ESS

## sd(Intercept) 1543

## sd(color1) 1163

## sd(color2) 1103

## cor(Intercept,color1) 2705

## cor(Intercept,color2) 1289

## cor(color1,color2) 1570

##

## Population-Level Effects:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## Intercept 0.03 0.22 -0.40 0.48 1.00 2196 2212

## color1 2.22 0.26 1.71 2.74 1.00 3108 2349

## color2 0.35 0.42 -0.49 1.17 1.00 1817 1923

##

## Samples were drawn using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

## and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

## scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).

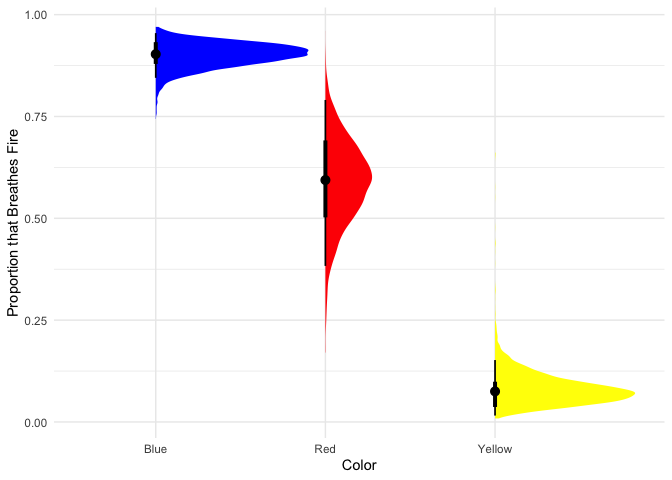

Now let’s plot the proportion of dragons that breathe fire by color:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

dragons %>% data_grid(color) %>%

add_fitted_draws(logit_model, re_formula=NA, scale='response') %>%

ggplot(aes(x=color, y=.value, fill=color)) +

stat_halfeye(point_interval=median_hdi, show.legend=FALSE) +

scale_fill_manual(values=c('blue', 'red', 'yellow')) +

xlab("Color") +

ylab("Proportion that Breathes Fire") +

theme_minimal()

Looks like most blue dragons breathe fire, red dragons are only slightly more likely to breathe fire than not, and few yellow dragons breathe fire.

Your turn! Test whether other variables predict breathesFire.

1

2

3

4

5

#Build your model here:

#Plot your results:

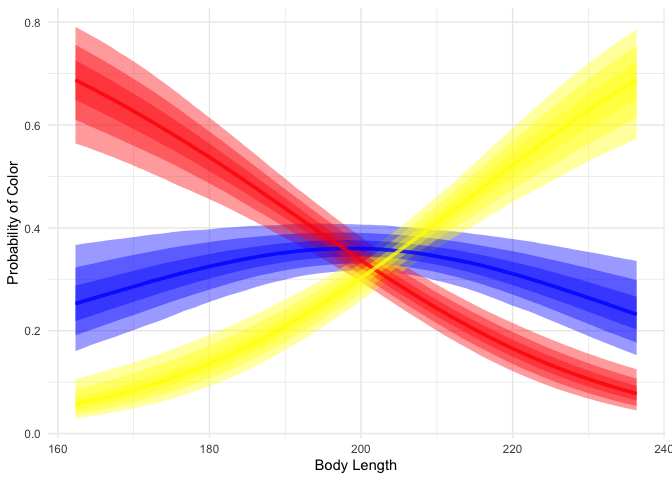

Bayesian Multinomial Regression

One serious advantage of going Bayesian is that you get immediate access to lots of other model types that require significant effort to get from existing Frequentist packages. One example is multinomial regression- this is like logistic regression, but with more than two unordered categories.

Instead of using color to predict body length, let’s see if body length predicts color:

1

2

3

4

5

multi_model <- brm(color ~ bodyLength,

data=dragons, file='color', family=categorical,

prior=prior(normal(0, 2)))

summary(multi_model, prior=TRUE)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

## Family: categorical

## Links: muRed = logit; muYellow = logit

## Formula: color ~ bodyLength

## Data: dragons (Number of observations: 480)

## Samples: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

## total post-warmup samples = 4000

##

## Priors:

## b_muRed ~ normal(0, 2)

## b_muYellow ~ normal(0, 2)

##

## Population-Level Effects:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## muRed_Intercept 5.62 1.46 2.76 8.52 1.00 3441 3214

## muYellow_Intercept -7.12 1.67 -10.29 -3.86 1.00 3229 2857

## muRed_bodyLength -0.03 0.01 -0.04 -0.01 1.00 3399 3110

## muYellow_bodyLength 0.03 0.01 0.02 0.05 1.00 3289 2852

##

## Samples were drawn using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

## and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

## scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).

Let’s plot the proportion of dragons of each color by body length:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

dragons %>% data_grid(bodyLength=seq_range(bodyLength, 100)) %>%

add_fitted_draws(multi_model, scale='response') %>%

ggplot(aes(x=bodyLength, y=.value)) +

stat_lineribbon(aes(color=.category, fill=.category),

alpha=0.4, show.legend=FALSE) +

scale_color_manual(values=c('blue', 'red', 'yellow')) +

scale_fill_manual(values=c('blue', 'red', 'yellow')) +

xlab("Body Length") +

ylab("Probability of Color") +

theme_minimal()

We can see that while short dragons are likely to be red, long dragons are likely to be yellow, and mid-length dragons are likely to be blue.

Bayesian Multilevel Unequal Variances Regression

Another extremely useful example of a model that integrates seamlessly

in brms is unequal variance regression. In our model using diet to

predict test scores, we never checked that the variances in test scores

between dragons with different diets was equal. Since this is an

assumption of that model, it could be bad if that assumption doesn’t

hold. An easy way to get around this in Bayesian regression is to simply

estimate both a mean and a variance for each diet:

1

2

3

4

5

6

model.diet.uv <- brm(bf(testScore ~ diet + (1+diet|mountainRange),

sigma ~ diet + (1+diet|mountainRange)),

data=dragons, file='diet_uv',

prior=set_prior(paste0('normal(0, ', sd(dragons$testScore), ')')))

summary(model.diet.uv, prior=TRUE)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

## Family: gaussian

## Links: mu = identity; sigma = log

## Formula: testScore ~ diet + (1 + diet | mountainRange)

## sigma ~ diet + (1 + diet | mountainRange)

## Data: dragons (Number of observations: 480)

## Samples: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

## total post-warmup samples = 4000

##

## Priors:

## b ~ normal(0, 23.0088071104418)

## Intercept ~ student_t(3, 51, 26.1)

## Intercept_sigma ~ student_t(3, 0, 2.5)

## L ~ lkj_corr_cholesky(1)

## sd ~ student_t(3, 0, 26.1)

## sd_sigma ~ student_t(3, 0, 26.1)

##

## Group-Level Effects:

## ~mountainRange (Number of levels: 8)

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat

## sd(Intercept) 10.78 3.40 6.15 19.37 1.00

## sd(diet1) 2.33 1.75 0.11 6.64 1.00

## sd(diet2) 4.47 1.95 1.22 9.15 1.00

## sd(sigma_Intercept) 0.13 0.09 0.01 0.35 1.00

## sd(sigma_diet1) 0.22 0.13 0.02 0.54 1.00

## sd(sigma_diet2) 0.15 0.11 0.01 0.41 1.00

## cor(Intercept,diet1) 0.03 0.48 -0.85 0.87 1.00

## cor(Intercept,diet2) 0.74 0.25 0.05 0.99 1.00

## cor(diet1,diet2) -0.28 0.45 -0.93 0.74 1.00

## cor(sigma_Intercept,sigma_diet1) 0.08 0.46 -0.80 0.87 1.00

## cor(sigma_Intercept,sigma_diet2) -0.25 0.46 -0.93 0.73 1.00

## cor(sigma_diet1,sigma_diet2) -0.42 0.45 -0.96 0.68 1.00

## Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## sd(Intercept) 1699 2357

## sd(diet1) 1709 2025

## sd(diet2) 1530 1015

## sd(sigma_Intercept) 1036 1492

## sd(sigma_diet1) 1042 1528

## sd(sigma_diet2) 1094 1931

## cor(Intercept,diet1) 3565 2868

## cor(Intercept,diet2) 2202 2767

## cor(diet1,diet2) 3147 2916

## cor(sigma_Intercept,sigma_diet1) 2046 2306

## cor(sigma_Intercept,sigma_diet2) 2546 2460

## cor(sigma_diet1,sigma_diet2) 2248 2533

##

## Population-Level Effects:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## Intercept 49.20 4.04 41.03 57.44 1.00 1289 1798

## sigma_Intercept 2.39 0.08 2.25 2.54 1.00 2288 2156

## diet1 -15.53 1.62 -18.63 -12.27 1.00 1900 2589

## diet2 15.41 2.09 11.08 19.37 1.00 1885 2209

## sigma_diet1 0.16 0.11 -0.05 0.41 1.00 2260 2164

## sigma_diet2 0.02 0.09 -0.14 0.22 1.00 2306 1814

##

## Samples were drawn using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

## and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

## scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).

Let’s plot the predicted mean and standard deviation of test scores by diet:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

draws <- dragons %>%

data_grid(diet) %>%

add_fitted_draws(model.diet.uv, dpar='sigma', re_formula=NA)

draws %>%

ggplot(aes(x=diet, y=.value)) +

stat_halfeye(point_interval=median_hdi) + ylim(0, NA) +

xlab("Diet") + ylab("Test Score") +

theme_minimal()

1

2

3

4

5

draws %>%

ggplot(aes(x=diet, y=sigma)) +

stat_halfeye(point_interval=median_hdi) + ylim(0, NA) +

xlab("Diet") + ylab("Std Deviation Test Score") +

theme_minimal()

It looks like the variation in test scores might be smaller for vegetarian dragons than for carnivorous dragons, though the difference is small. Does this unequal variance model do better than our old model?

1

loo(model.diet, model.diet.uv)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

## Output of model 'model.diet':

##

## Computed from 4000 by 480 log-likelihood matrix

##

## Estimate SE

## elpd_loo -1832.9 21.6

## p_loo 24.4 4.0

## looic 3665.9 43.2

## ------

## Monte Carlo SE of elpd_loo is NA.

##

## Pareto k diagnostic values:

## Count Pct. Min. n_eff

## (-Inf, 0.5] (good) 474 98.8% 1097

## (0.5, 0.7] (ok) 4 0.8% 230

## (0.7, 1] (bad) 2 0.4% 87

## (1, Inf) (very bad) 0 0.0% <NA>

## See help('pareto-k-diagnostic') for details.

##

## Output of model 'model.diet.uv':

##

## Computed from 4000 by 480 log-likelihood matrix

##

## Estimate SE

## elpd_loo -1832.7 21.8

## p_loo 42.3 6.7

## looic 3665.3 43.7

## ------

## Monte Carlo SE of elpd_loo is NA.

##

## Pareto k diagnostic values:

## Count Pct. Min. n_eff

## (-Inf, 0.5] (good) 469 97.7% 627

## (0.5, 0.7] (ok) 4 0.8% 176

## (0.7, 1] (bad) 7 1.5% 18

## (1, Inf) (very bad) 0 0.0% <NA>

## See help('pareto-k-diagnostic') for details.

##

## Model comparisons:

## elpd_diff se_diff

## model.diet.uv 0.0 0.0

## model.diet -0.3 6.6

In this case, it looks like the model without equal variances does about as well as the model with unequal variances. That means we can probably assume equal variances without any problems. But this isn’t always the case, and many research programs are dedicated to explaining why different groups have different variances!

Conclusions

In this tutorial we demonstrated the basics of using brms to run

Bayesian regressions that directly parallel what you’re likely used to

running with lm and lmer. We also demonstrated how to run Bayesian

significant tests with bayestestR and how to plot results from these

models using tidybayes. Though there are many more details to

specifying, running, and interpreting Bayesian models, hopefully this

tutorial convinced you that making the first step is easier than you

imagined!

Convergence

Some parting tips and tricks:

Like with Frequentist multilevel models, one of the biggest concerns

with convergence is whether you have enough data for your model

structure. Specifically, you need enough observations for every

combination of population-level and group-level effect in order for your

model to be well-defined. Unlike lmer, brms will try to fit a model

even if you don’t have enough data. But in this case, you will either

get unstable results, or your model will only be informed by your

priors.

There are a few different convergence problems that brms will tell you

about, however. If Rhat for any of your parameters is greater than

1.1, then your model has not converged and the samples from your model

don’t match the true posterior. Here, brms will likely instruct you to

increase the number of samples and/or turn on thinning, which reduces

the autocorrelation between samples. If you have divergent transitions,

then brms will tell you to increase the adapt_delta parameter, which

lowers the step size of the estimator. Finally, you might get warnings

about max_treedepth or ESS, both of which brms will give you

recommendations for.

In my experience, however, one of the main reasons that these warnings

might persist is that your priors are underspecified. If you have flat

or extremely wide priors, then brms has to search a massive parameter

space to find the most likely values. But if you constrain your prior to

a reasonable degree, not only will your model fit faster, but it will

also have less convergence issues. No matter what, you want to make sure

that your priors truly reflect your expectations and that your results

aren’t too heavily influenced by your specific choice of prior.