ggplot2 workshop

Welcome! This is an intermediate-level workshop about the R package

ggplot2. It’s co-authored by

Allie and

Maria. We’ll cover custom aesthetics,

plotting model estimates, multi-layered plots, and advanced geoms

(spaghetti and rainbow plots!).

Table of Contents

- multi-layer plots (Allie)

- plotting model estimates (Maria)

- customizing plots (Maria)

- how to make a spaghetti plot (Allie)

- how to make a raincloud plot (Allie)

Tidy data

Like other packages in the tidyverse,

ggplot2 works best when your data are “tidy”: each column is a

variable, and each row is an observation. How exactly you define an

“observation” is going to be dependent on your question and desired

visualization, and it’s not uncommon to use a couple different versions

of your dataframe when playing around with visualizations.

Today we’ll be working with the dragons dataset that we’ve all come to know and love. This is a fictional dataset about dragons. Each dragon has one row. We have information about each dragon’s body length and cognitive test score. We also have some other information about each dragon: We know about the mountain range where it lives, color, diet, and whether or not it breathes fire.

Let’s load it in, along with some other packages.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

#change some settings

options(scipen=999) #turn off scientific notation

options(contrasts = c("contr.sum","contr.poly")) #this tweaks the sum-of-squares settings to make sure the output of Anova(model) and summary(model) are consistent and appropriate when a model has interaction terms

# load in packages

library(dplyr) #for data wrangling

library(lme4) #fit the models

library(lmerTest) #gives p-values and more info

library(Rmisc) #summary stats

library(emmeans) #for extracting model estimates

library(ggplot2) #for plotting, duh!

# load the data

dragons <- read.csv("2020-10-21-dragon-data.csv")

Just as a reminder, let’s take a peak at our dataframe:

1

2

#take a peek at the header

head(dragons)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

## testScore bodyLength mountainRange color diet breathesFire

## 1 0.0000000 175.5122 Bavarian Blue Carnivore 1

## 2 0.7429138 190.6410 Bavarian Blue Carnivore 1

## 3 2.5018247 169.7088 Bavarian Blue Carnivore 1

## 4 3.3804301 188.8472 Bavarian Blue Carnivore 1

## 5 4.5820954 174.2217 Bavarian Blue Carnivore 0

## 6 12.4536350 183.0819 Bavarian Blue Carnivore 1

1

2

#view the full dataset

View(dragons)

We have 2 continuous variables: testScore and bodyLength. The rest

of the variables are categorical. This gives us lots of options for

creatively visualizing relationships between different variables of

interest!

Multi-Layered Plots

I’m going to assume that you have some prior knowledge of R and ggplot2, but not much. Let’s start with a basic plot.

1

ggplot(data = dragons)

If we call ggplot() without specifying any variables, it just generates a blank square! This is actually the bottom layer of every plot. It’s a blank slate, waiting for us to layer data on top.

Let’s say our first research question is whether the color of the dragon is related to its intelligence. What happens when we specify those variables, but don’t add any geoms? We initialize a grid and axes, but don’t actually plot any data.

1

ggplot(data = dragons, aes(x = color, y = breathesFire))

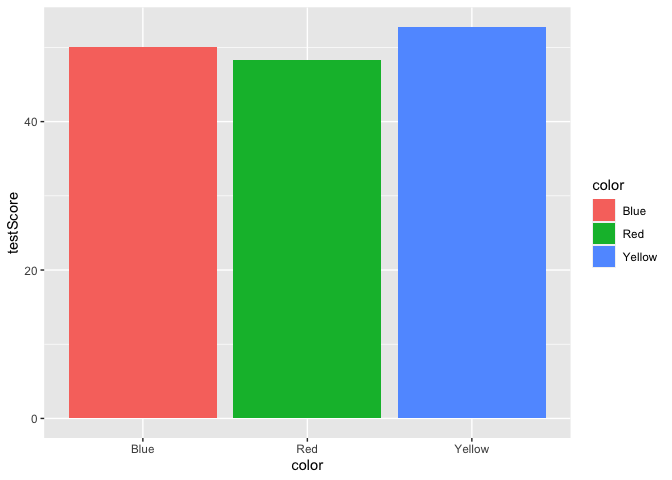

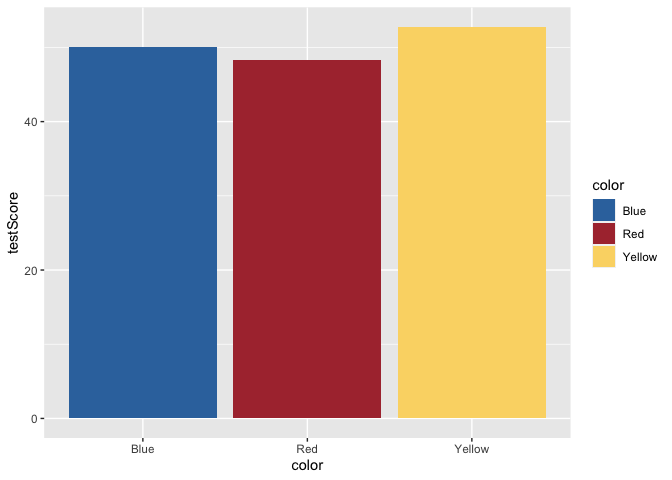

Let’s add a basic bar plot layer. We can also color the bars using the fill argument.

1

2

ggplot(data = dragons, aes(x = color, y = testScore, fill = color)) +

geom_bar(stat = "summary")

Yikes, we’ve generated a Stroop effect plot. Let’s specify a custom color palette and add that palette as a layer to our plot.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

scale_fill_dragon <- function(...){

library(scales)

discrete_scale("fill","dragon",manual_pal(values = c("#3574AC","#AD343C","#FBD774")), ...)

}

ggplot(data = dragons, aes(x = color, y = testScore, fill = color)) +

scale_fill_dragon() +

geom_bar(stat = "summary")

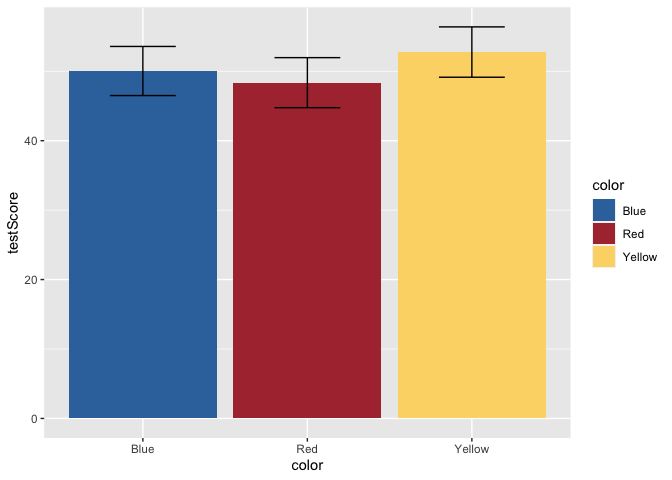

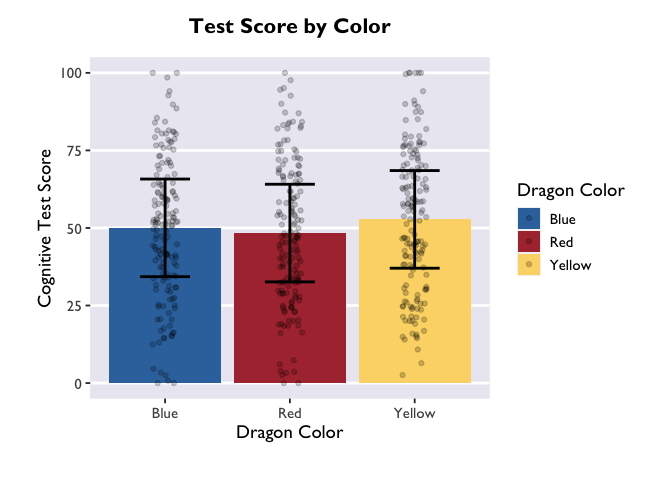

Great! That makes more sense. Now, let’s add some error bars for 95% confidence intervals. To do this, we’ll first calculate a small summary dataframe that will give us CIs. If you open this dataframe, you’ll see that you also get SE and SD measures.

1

2

3

4

5

6

dragons_sum <- summarySE(dragons, measurevar = "testScore", groupvars = c("color"))

ggplot(data = dragons, aes(x = color, y = testScore, fill = color)) +

scale_fill_dragon() +

geom_bar(stat = "summary") +

geom_errorbar(data = dragons_sum, aes(ymin=testScore-ci, ymax=testScore+ci), width = 0.4)

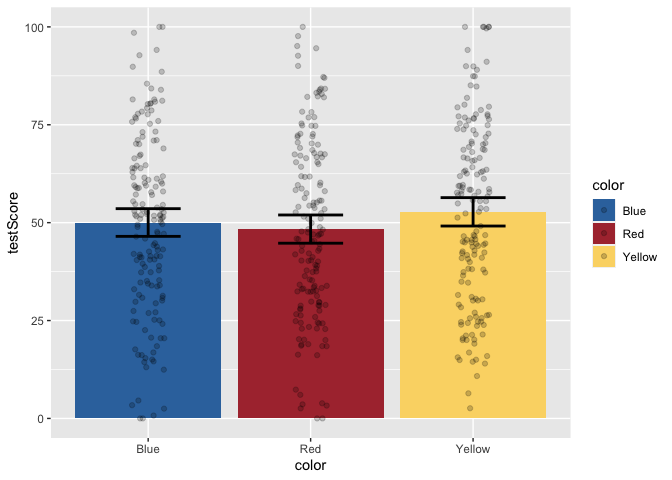

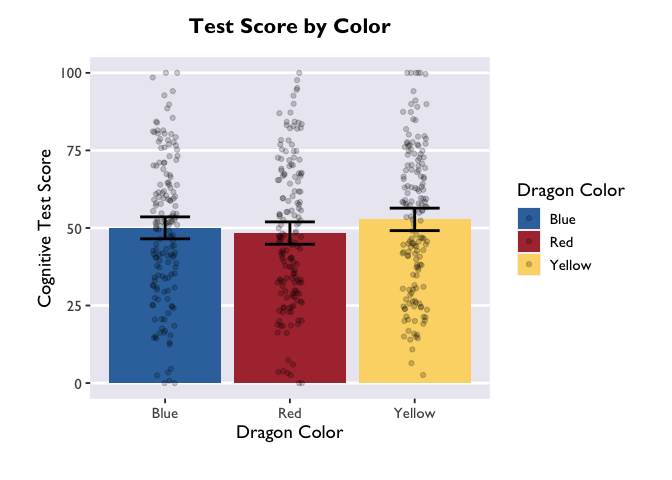

But, this bar plot doesn’t tell us much about the distribution of the data, does it? Let’s add some points on top of the bars. We’ll also apply some horizontal jitter and adjust the opacity to make the points visible. We can also make the error bars thicker so they stand out.

1

2

3

4

5

ggplot(data = dragons, aes(x = color, y = testScore, fill = color)) +

scale_fill_dragon() +

geom_bar(stat = "summary") +

geom_errorbar(data = dragons_sum, aes(ymin=testScore-ci, ymax=testScore+ci), width = 0.4, size = 1) +

geom_jitter(width = 0.1, height = 0, alpha = 0.2)

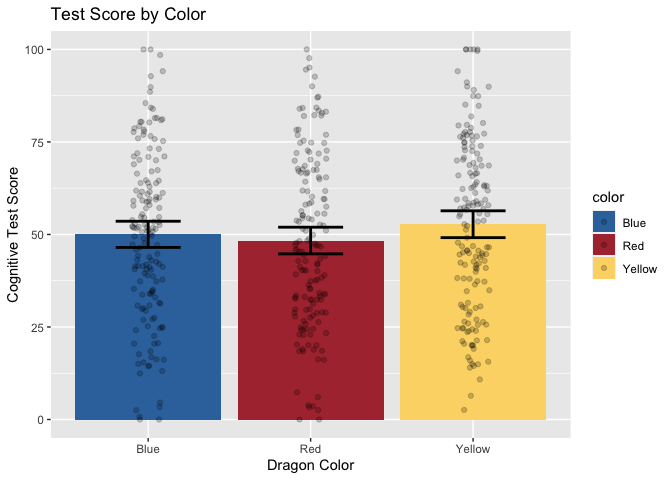

Now, let’s add layers for axis labels and a title.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

ggplot(data = dragons, aes(x = color, y = testScore, fill = color)) +

scale_fill_dragon() +

geom_bar(stat = "summary") +

geom_errorbar(data = dragons_sum, aes(ymin=testScore-ci, ymax=testScore+ci), width = 0.4, size = 1) +

geom_jitter(width = 0.1, height = 0, alpha = 0.2) +

xlab("Dragon Color") +

ylab("Cognitive Test Score") +

ggtitle("Test Score by Color")

Finally, just to make it pretty, let’s apply a custom theme that I use for my plots. For the sake of time, we won’t be covering the details of custom themes today, but you can find great tutorials online. These functions allow you to specify all your favorite aesthetic choices, and then easily apply those tweaks to future plots with just one line of code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

#if you want to access extra fonts, you can run the following lines of code.

#if you don't care during the tutorial, disable them. Loading the fonts (only the first time) can take several minutes if they are not already installed into R Studio.

library(extrafont)

#font_import() #first time only

#loadfonts(device= "win")

#here's my custom plotting theme. It's a function that specifies background colors, text font/size/position, and spacing.

theme_allie <- function(base_size = 14, base_family = "Gill Sans MT"){

theme_gray(base_size = base_size, base_family = base_family) %+replace%

theme(

plot.margin=grid::unit(c(1,1,1,1), "cm"),

plot.title = element_text(face = "bold", size = rel(1.15), hjust = 0.5, vjust = 5),

panel.border = element_blank(),

panel.background = element_rect(fill = "#EAEAF2", colour = "#EAEAF2"),

strip.background = element_rect(fill = NA),

panel.grid.major.y = element_line(size = 1, colour = "white"),

panel.grid.minor.y = element_blank(),

panel.grid.major.x = element_blank(),

panel.grid.minor.x = element_blank()

)

}

ggplot(data = dragons, aes(x = color, y = testScore, fill = color)) +

scale_fill_dragon("Dragon Color") +

geom_bar(stat = "summary") +

geom_errorbar(data = dragons_sum, aes(ymin=testScore-ci, ymax=testScore+ci), width = 0.4, size = 1) +

geom_jitter(width = 0.1, height = 0, alpha = 0.2) +

xlab("Dragon Color") +

ylab("Cognitive Test Score") +

ggtitle("Test Score by Color") +

theme_allie()

1

2

# if we wanted to save the plot in our current working directory, we could run the line below.

#ggsave("dragon_color.png", dpi = 300, width = 4, height = 4, units = "in")

Plotting model estimates

Now that we know how to create beautiful multi-layered plots, let’s

learn how to plot the results of our mixed models! The emmeans package

is the star of the show here. Short for “estimated marginal means”, it

extracts the beta values, CIs, and more from a fitted lmer object.

Let’s start with the same question as we started with above – how is

color related to intelligence?

Linear mixed model with a categorical predictor

First we have to fit our lmer model. If you’re still new to emmeans,

it’s best to save the fitted model as an object so that you can play

around with different calls. At the end of the section I’ll show you the

fastest way to go from model -> plot.

1

2

model <- lmer(testScore ~ color + (1|mountainRange), data=dragons)

summary(model)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

## Linear mixed model fit by REML. t-tests use Satterthwaite's method [

## lmerModLmerTest]

## Formula: testScore ~ color + (1 | mountainRange)

## Data: dragons

##

## REML criterion at convergence: 3977.8

##

## Scaled residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -3.4828 -0.6343 -0.0026 0.6986 3.0139

##

## Random effects:

## Groups Name Variance Std.Dev.

## mountainRange (Intercept) 349.1 18.68

## Residual 220.9 14.86

## Number of obs: 480, groups: mountainRange, 8

##

## Fixed effects:

## Estimate Std. Error df t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 50.3860 6.6407 7.0000 7.587 0.000128 ***

## color1 -0.3499 0.9594 470.0000 -0.365 0.715490

## color2 -2.0290 0.9594 470.0000 -2.115 0.034970 *

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Correlation of Fixed Effects:

## (Intr) color1

## color1 0.000

## color2 0.000 -0.500

The results are not too exciting, but let’s make a dataframe with the marginal means anyway.

1

2

model_df <- emmeans(model, ~ color) %>% as.data.frame()

head(model_df)

1

2

3

4

## color emmean SE df lower.CL upper.CL

## 1 Blue 50.03612 6.709633 7.295226 34.29959 65.77265

## 2 Red 48.35704 6.709633 7.295226 32.62051 64.09356

## 3 Yellow 52.76494 6.709633 7.295226 37.02841 68.50147

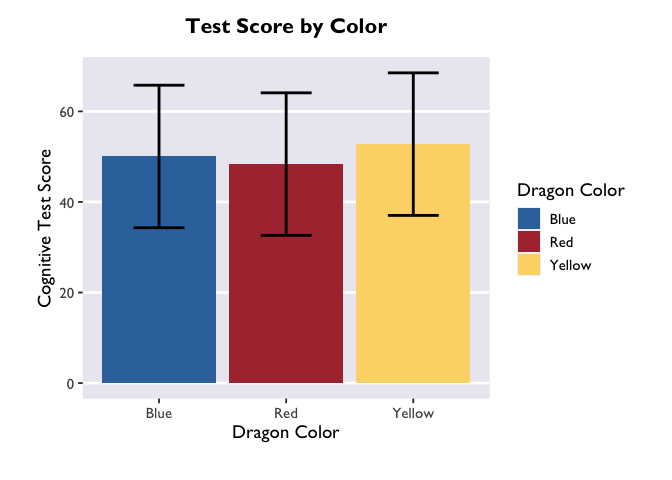

Sweet! After converting the emGrid object to a dataframe, we now have estimates of test score as a function of color (the column “emmean”), as well as standard error, degrees of freedom, and upper/lower CIs. Let’s plot these using Allie’s custom theme:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

ggplot(model_df, aes(x = color, y = emmean, fill = color)) +

scale_fill_dragon("Dragon Color") +

geom_col() +

geom_errorbar(aes(ymin=lower.CL, ymax=upper.CL), width = 0.4, size = 1) +

xlab("Dragon Color") +

ylab("Cognitive Test Score") +

ggtitle("Test Score by Color") +

theme_allie()

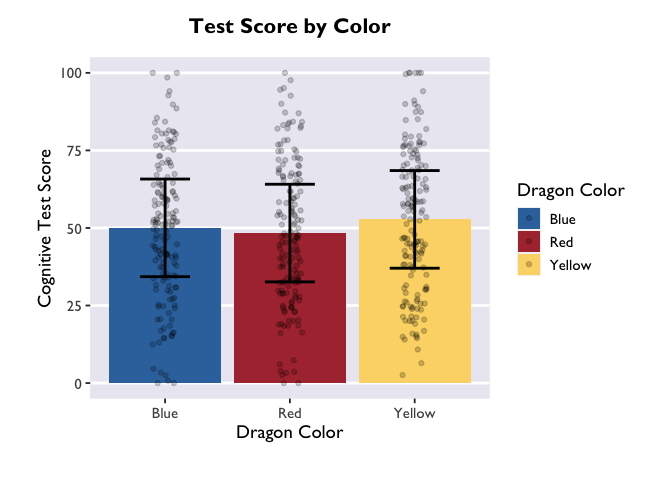

The biggest difference between plotting in the emmeans-verse and in

the way Allie showed above is that your y variable will almost always be

“emmean” and you don’t have to compute confidence intervals yourself.

But if you want to add information about the raw data (like the jitter

above), then you’ll need to add a layer that takes data from the source

dataframe. Note that you only need to specify the dimension on which

your variable is different from the one in the main ggplot call – i.e.,

I only had to specify y=testScore in the geom_jitter() call.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

ggplot(model_df, aes(x = color, y = emmean, fill = color)) +

scale_fill_dragon("Dragon Color") +

geom_col() +

geom_errorbar(aes(ymin=lower.CL, ymax=upper.CL), width = 0.4, size = 1) +

geom_jitter(data=dragons, aes(y=testScore), width = 0.1, height = 0, alpha = 0.2) +

xlab("Dragon Color") +

ylab("Cognitive Test Score") +

ggtitle("Test Score by Color") +

theme_allie()

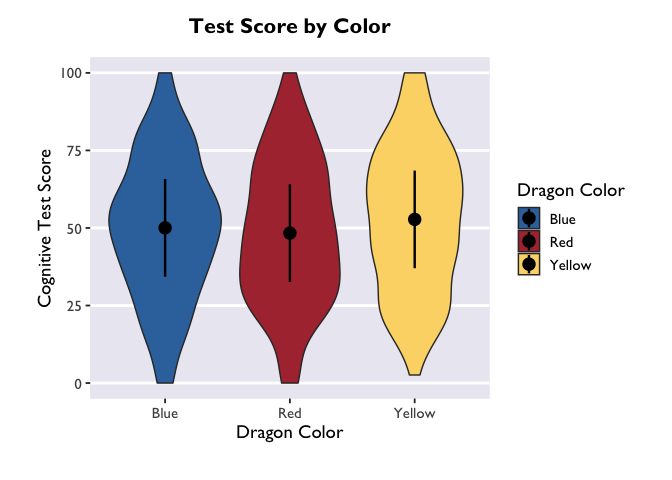

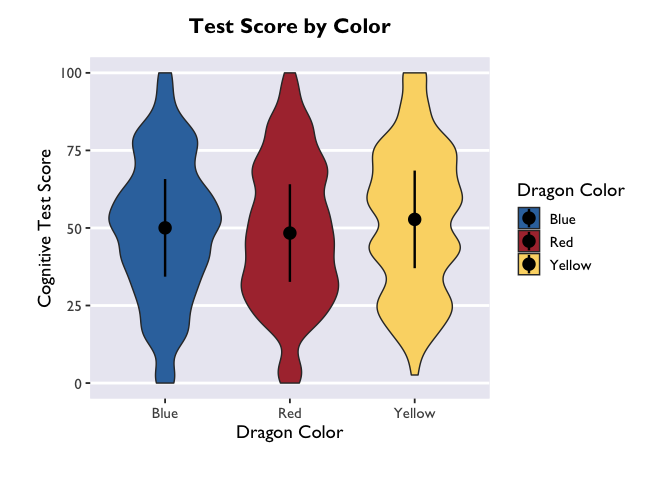

Another way to convey this information is with a violin plot, where the

estimate is plotted with geom_pointrange() and raw data as violin

widths:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

ggplot(model_df, aes(x = color, y = emmean, fill = color)) +

scale_fill_dragon("Dragon Color") +

geom_violin(data=dragons, aes(y=testScore)) +

geom_pointrange(aes(ymin=lower.CL, ymax=upper.CL), size = 0.85) +

xlab("Dragon Color") +

ylab("Cognitive Test Score") +

ggtitle("Test Score by Color") +

theme_allie()

If you want to adjust the amount of smoothing in the violin (i.e., how

lumpy it is), you do that with the bw argument. Because bw sets the

standard deviation of the smoothing kernel for the distributions, the

magnitude of the bw value needed to achieve your desired results will

vary as a function of your data.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

ggplot(model_df, aes(x = color, y = emmean, fill = color)) +

scale_fill_dragon("Dragon Color") +

geom_violin(data=dragons, aes(y=testScore), bw=4.5) +

geom_pointrange(aes(ymin=lower.CL, ymax=upper.CL), size = 0.85) +

xlab("Dragon Color") +

ylab("Cognitive Test Score") +

ggtitle("Test Score by Color") +

theme_allie()

Linear mixed model with an interaction between categorical predictors

So far, so good. But what if we have a model with an interaction term? Let’s fit one and find out!

1

2

model2 <- lmer(testScore ~ color*diet + (1|mountainRange), data=dragons)

summary(model2)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

## Linear mixed model fit by REML. t-tests use Satterthwaite's method [

## lmerModLmerTest]

## Formula: testScore ~ color * diet + (1 | mountainRange)

## Data: dragons

##

## REML criterion at convergence: 3671.2

##

## Scaled residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -3.0978 -0.5708 -0.0243 0.5190 4.6698

##

## Random effects:

## Groups Name Variance Std.Dev.

## mountainRange (Intercept) 82.64 9.091

## Residual 121.35 11.016

## Number of obs: 480, groups: mountainRange, 8

##

## Fixed effects:

## Estimate Std. Error df t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 49.98257 3.25369 6.74874 15.362 0.00000168 ***

## color1 -0.46020 0.71397 463.78929 -0.645 0.520

## color2 -0.42132 0.71766 464.03951 -0.587 0.557

## diet1 -16.25262 0.92164 470.83945 -17.634 < 0.0000000000000002 ***

## diet2 17.15942 0.89337 470.92818 19.208 < 0.0000000000000002 ***

## color1:diet1 -0.19162 1.02754 463.93696 -0.186 0.852

## color2:diet1 -0.02199 1.00207 464.03628 -0.022 0.983

## color1:diet2 -0.70805 1.01244 464.39095 -0.699 0.485

## color2:diet2 0.42549 1.02280 464.32294 0.416 0.678

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Correlation of Fixed Effects:

## (Intr) color1 color2 diet1 diet2 clr1:1 clr2:1 clr1:2

## color1 -0.001

## color2 0.000 -0.497

## diet1 0.005 0.027 -0.120

## diet2 -0.006 0.007 0.084 -0.663

## color1:dit1 0.004 0.041 0.035 0.012 -0.021

## color2:dit1 -0.015 0.036 -0.042 -0.051 0.018 -0.473

## color1:dit2 0.003 -0.021 -0.036 0.032 -0.042 -0.511 0.246

## color2:dit2 0.007 -0.029 0.008 -0.014 0.074 0.243 -0.482 -0.520

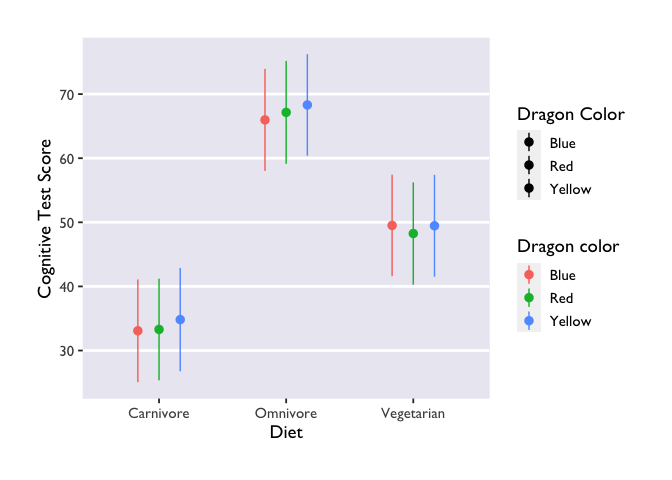

Whoa! Major effects of diet on test scores. Converting the model estimates to a dataframe is as simple as the following command:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

model2_df <- emmeans(model2, ~ color | diet) %>% as.data.frame()

ggplot(model2_df, aes(x=diet, y=emmean, fill=color, color=color)) +

scale_fill_dragon("Dragon Color") +

geom_pointrange(aes(ymin=lower.CL, ymax=upper.CL), position=position_dodge(0.5)) +

labs(x="Diet", y="Cognitive Test Score", color="Dragon color", fill="Dragon color") +

theme_allie()

Three things to note: first, we indicate that we want to extract

marginal means for the main terms and interactions with the | operator

(did you know it’s called a ‘pipe’??? TIL!). The * operator will do

exactly the same thing, and it has the added benefit of being more

similar to lmer syntax.

Second, we made another Stroop plot! The colors of the geoms don’t match the color names, and we no longer have Allie’s beautiful colors. Unfortunately, this shows the limits of custom color palettes – since they’re hard-coded, they need to have enough colors to cover all the different combinations of your discrete variables. So if you wanted to make an interaction plot like this with the same colors as Allie’s, you’d need to make another palette that has 9 values instead of 3.

Third, we have two legends! One where the geoms are colored and another

where they are black. This highlights the difference between the color

and fill arguments. Color is used to set the color of line-based

objects, like the outline of a bar, violin, ribbon, etc. It’s also used

to set the color of points. Given that our geom is a combination of

point & line, it’s only going to be modifiable by color arguments.

Fill is used to “fill in” empty spaces, like the inside of a column,

ribbon, or violin. Since we don’t have any geoms that take the fill

argument in this plot, then it just shows up as black. Getting rid of

fill=color and scale_fill_dragon() will get rid of the superfluous

legend.

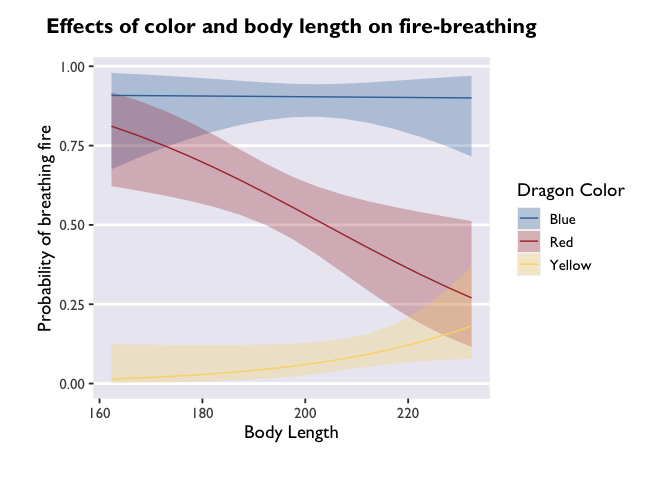

Generalized linear mixed model & continuous predictor variables

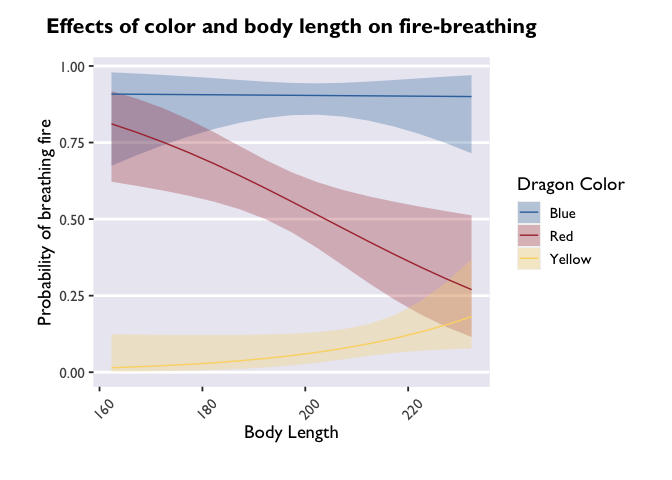

What if you want to plot the results of a generalized linear model? And what if you have a continuous predictor variable? Let’s investigate the relationship between color, bodyLength, and breathesFire to find out:

1

2

3

model3 <- glmer(breathesFire ~ color*bodyLength + (1|mountainRange), data=dragons, family=binomial(link = "logit"))

model3_df <- emmeans(model3, ~ color*bodyLength, type='response') %>% as.data.frame()

head(model3_df)

1

2

3

4

## color bodyLength prob SE df asymp.LCL asymp.UCL

## 1 Blue 201.3165 0.90383086 0.02537801 Inf 0.84134741 0.9433625

## 2 Red 201.3165 0.52274341 0.05436631 Inf 0.41676412 0.6267137

## 3 Yellow 201.3165 0.06265896 0.02400686 Inf 0.02912871 0.1296326

1

2

# to confirm that we only get point estimates for each categorical predictor

length(model3_df)

1

## [1] 7

First thing to note: I added the argument type='response' to the

emmeans call. This ensures that our estimates are back-transformed to

the same scale as the original variable, instead of being on the

log-odds scale. If you’re using only categorical predictors, then this

is the only emmeans modification you have to worry about.

Second thing to note: the names of our variables in the dataframe are

different from those in the lmer() dataframe! Instead of emmeans, we

have prob; degrees of freedom are now infinite; and the CIs are now

values of the asymptote (asymp.LCL, asymp.UCL) instead of the fixed

upper and lower bounds (lower.CL, upper.CL). These differences all have

to do with the logit link, but all you need to know in terms of plotting

is that you’ll have to adjust your variable names accordingly.

Finally, because we have a continuous predictor, there is a third thing

to note: we only got point estimates for the effect of color at the mean

value of bodyLength. But that’s not how we think about or want to plot

the effect of a continuous predictor! Thus, we need to specify the range

of bodyLength values that we want emmeans to return estimates from.

There are a number of ways to do this, and the “best” way is contingent

on your research question and/or desired visualization. And fortunately,

this method remains the same regardless of your model type (i.e., if

it’s lmer() or glmer()).

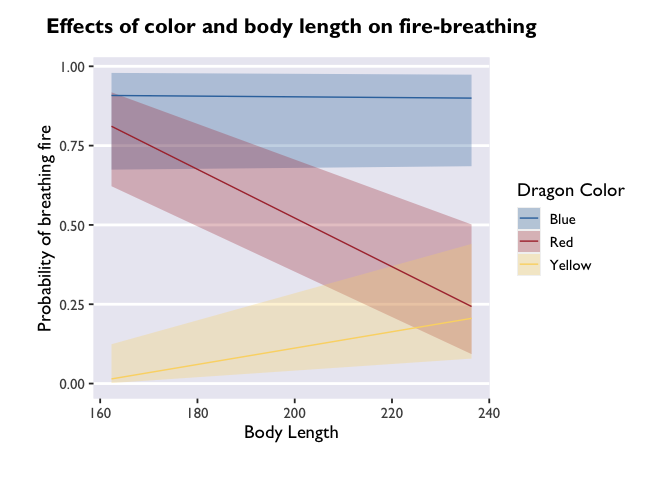

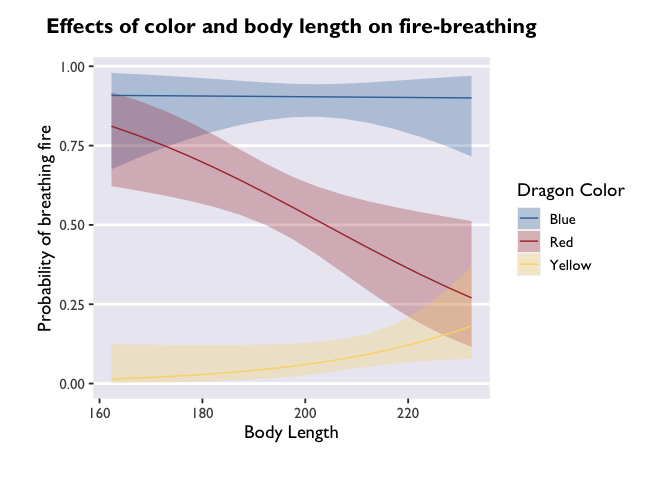

One approach is to get estimates from the lowest and highest values (i.e., the range) of bodyLength. Here’s how you do that:

1

2

3

# extracting estimates at the extremes and mean values of bodyLength

model3_df <- emmeans(model3, ~ color*bodyLength, type='response', cov.reduce=range) %>% as.data.frame()

head(model3_df)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

## color bodyLength prob SE df asymp.LCL asymp.UCL

## 1 Blue 162.3266 0.90822227 0.06654721 Inf 0.674224946 0.9793036

## 2 Red 162.3266 0.81107636 0.07497809 Inf 0.621985544 0.9180434

## 3 Yellow 162.3266 0.01460516 0.01656817 Inf 0.001549897 0.1239744

## 4 Blue 236.3625 0.89971296 0.06519867 Inf 0.685204776 0.9736679

## 5 Red 236.3625 0.24283279 0.10726832 Inf 0.092736596 0.5015619

## 6 Yellow 236.3625 0.20571388 0.09259853 Inf 0.078587479 0.4402323

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

# plot those estimates

ggplot(model3_df, aes(x=bodyLength, y=prob,fill=color)) +

geom_ribbon(aes(ymin=asymp.LCL, ymax=asymp.UCL), alpha=0.3) +

geom_line(aes(color=color)) +

scale_fill_dragon("Dragon Color") +

scale_color_manual(values=c("#3574AC","#AD343C","#FBD774")) +

labs(y='Probability of breathing fire', x='Body Length', color='Dragon Color', title='Effects of color and body length on fire-breathing') +

theme_allie()

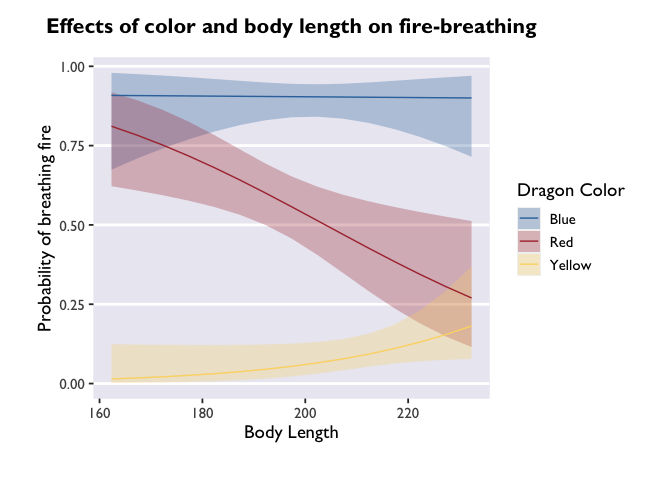

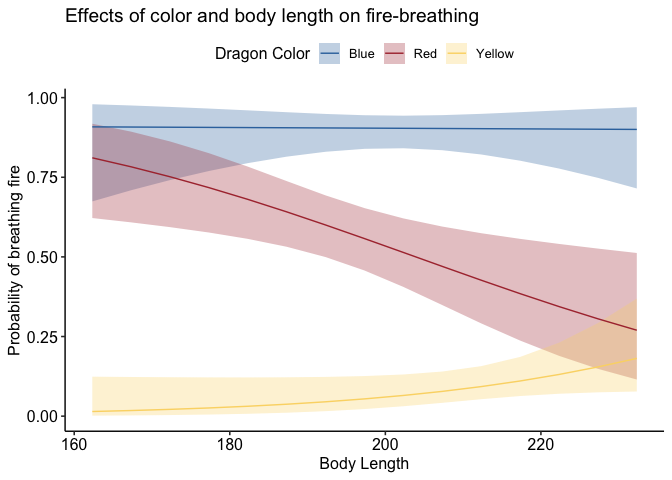

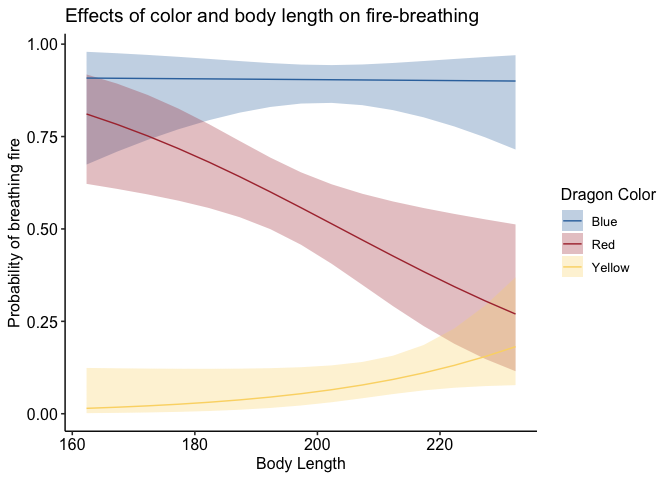

But if you want a more detailed representation of the effect, you can

write a quick function that tells emmeans() to extract estimates along

the whole range of bodyLength values in X-sized increments:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

# write a function to extract values of bodyLength in "precision"-sized increments

bodyLength_range <- function(bodyLength, precision=5) {

return(seq(min(dragons[,bodyLength], na.rm=TRUE),

max(dragons[,bodyLength], na.rm=TRUE),

precision))

}

# tell emmeans to extract estimates at values of bodyLength specified by the function bodyLength_range

model3_df <- emmeans(model3, ~ color*bodyLength, type='response', at=list(bodyLength=bodyLength_range('bodyLength'))) %>% as.data.frame()

head(model3_df)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

## color bodyLength prob SE df asymp.LCL asymp.UCL

## 1 Blue 162.3266 0.90822227 0.06654721 Inf 0.674224946 0.9793036

## 2 Red 162.3266 0.81107636 0.07497809 Inf 0.621985544 0.9180434

## 3 Yellow 162.3266 0.01460516 0.01656817 Inf 0.001549897 0.1239744

## 4 Blue 167.3266 0.90766865 0.05958259 Inf 0.709312449 0.9753722

## 5 Red 167.3266 0.78275913 0.07300889 Inf 0.608334845 0.8931490

## 6 Yellow 167.3266 0.01766287 0.01818495 Inf 0.002299758 0.1230034

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

# let's see the difference this makes in the plot!

ggplot(model3_df, aes(x=bodyLength, y=prob,fill=color)) +

geom_ribbon(aes(ymin=asymp.LCL, ymax=asymp.UCL), alpha=0.3) +

geom_line(aes(color=color)) +

scale_fill_dragon("Dragon Color") +

scale_color_manual(values=c("#3574AC","#AD343C","#FBD774")) +

labs(y='Probability of breathing fire', x='Body Length', color='Dragon Color',title='Effects of color and body length on fire-breathing') +

theme_allie()

Cool! The trends are still there, but now we have a more detailed depiction of how the probability of fire-breathing changes as a function of body length.

emmeans

is an immensely useful companion package for lme4 and lmerTest. The

vignettes on the page linked here are very helpful, and can be quite

illuminating about all the things you can do with fitted mixed models. I

highly recommend playing around with it to build up your knowledge about

mixed models!

And once you get familiar with emmeans & lmer, you can take the

fast-track to plotting model estimates:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

glmer(breathesFire ~ color*bodyLength + (1|mountainRange), data=dragons, family=binomial(link = "logit")) %>%

emmeans(., ~ color*bodyLength, type='response', at=list(bodyLength=bodyLength_range('bodyLength'))) %>%

as.data.frame() %>%

ggplot(., aes(x=bodyLength, y=prob,fill=color)) +

geom_ribbon(aes(ymin=asymp.LCL, ymax=asymp.UCL), alpha=0.3) +

geom_line(aes(color=color)) +

scale_fill_dragon("Dragon Color") +

scale_color_manual(values=c("#3574AC","#AD343C","#FBD774")) +

labs(y='Probability of breathing fire', x='Body Length', color='Dragon Color',title='Effects of color and body length on fire-breathing') +

theme_allie()

Customizing your plots

Perhaps my favorite thing about ggplot2 is how much flexibility and

control you have over your plots. Since I don’t know what you don’t

know, this section is going to be a compilation of aesthetic tweaks that

I’ve had to make in my very short research career. If there’s a specific

thing you want to know how to do, let me know and I’ll update the post!

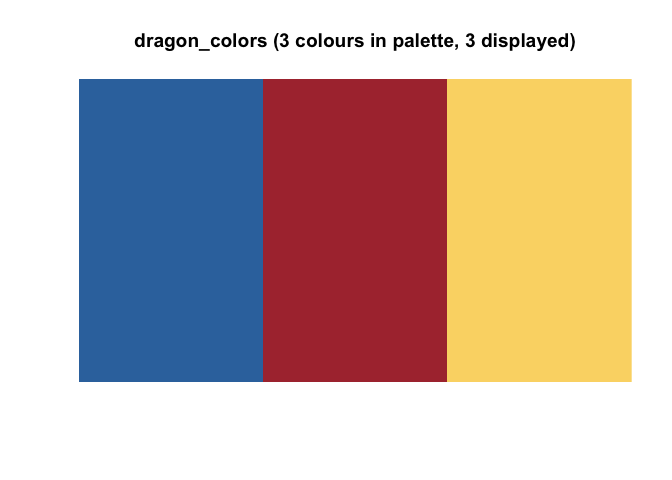

Creating a custom color palette

Like all things programming, there are multiple ways to do this.

Allie demonstrated one method above that I’ll reproduce here:

1

2

3

4

scale_fill_dragon <- function(...){

library(scales)

discrete_scale("fill","dragon",manual_pal(values = c("#3574AC","#AD343C","#FBD774")), ...)

}

I had no idea you could make a custom palette like this! I’ve always

used the paletti package to do

this. All you do is specify a vector of HEX codes and pass it to some

nested arguments from the packge:

1

2

3

4

5

6

# load the package

library(paletti)

# specify the colors

dragon_colors <- c("#3574AC","#AD343C","#FBD774")

# preview the palette

viz_palette(dragon_colors)

1

2

3

# create the palette

dragon_fill <- get_scale_fill(get_pal(dragon_colors))

dragon_color <- get_scale_color(get_pal(dragon_colors))

Custom palettes are great for a lot of reasons, but they can take a lot of work to hone. Sourcing colors for palettes is one of my favoite forms of procrastination, but if you just want to get things done, here is an excellent resource canvassing color palettes available to R users. I don’t know if it’s completely comprehensive, but it’s pretty darn close. It also has some great resources for generating HEX codes if you are interested in making a plotting theme but have no idea where to start.

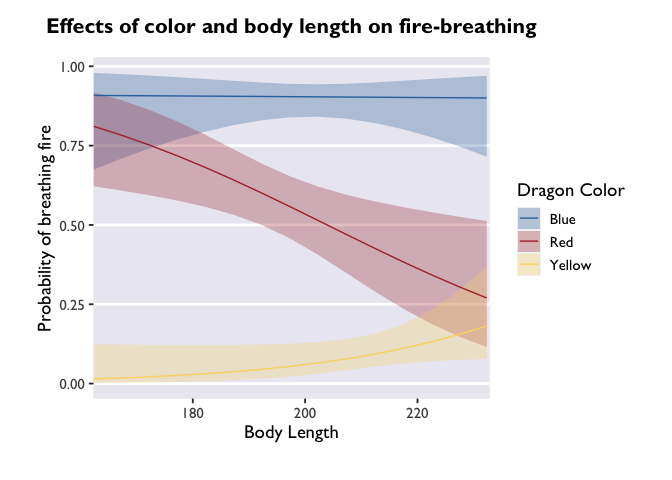

Modifying axes

Let’s take a look at one of our glmer() plots. You’ll notice that I’m

saving this ggplot call to the variable p. I’m doing this to take

advantage of the syntax and demonstrate that you can modify plots even

after they’ve been saved. That’s one of the many beautiful things about

ggplots: you can just keep adding layers until you get the plot of your

dreams. [am i the only one who dreams about beautiful plots?]

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

p <- ggplot(model3_df, aes(x=bodyLength, y=prob,fill=color)) +

geom_ribbon(aes(ymin=asymp.LCL, ymax=asymp.UCL), alpha=0.3) +

geom_line(aes(color=color)) +

scale_fill_dragon("Dragon Color") +

scale_color_manual(values=c("#3574AC","#AD343C","#FBD774")) +

labs(y='Probability of breathing fire', x='Body Length', color='Dragon Color', title='Effects of color and body length on fire-breathing') +

theme_allie()

p

It’s beautiful, right? But what if you don’t want that extra gray space

around the edges of the x-axis? That’s where the expand argument of

scale_x_continuous comes in. This allows you to set the “range

expansion constants” the ggplot uses to add padding around the axes. For

continuous variables, like we have, the default is to expand the scale

by 5% on each side. For discrete variables (scale_x_discrete), the

default is 0.6 units.

Based on my tinkering, it seems like small increases in the first or

third value of expand will result in big changes at the leftmost and

rightmost points on the x-axis, respectively. Small increases to the

second or fourth values will results in small changes at the leftmost

and rightmost points on the x-axis. There is definitely a better

explanation for this (probably having to do with y-values), but I’ll

leave that for you to discover! For now, I’ll set all the values except

the last to 0 so you can get an idea of how this shifts the plotting

space:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

ggplot(model3_df, aes(x=bodyLength, y=prob,fill=color)) +

geom_ribbon(aes(ymin=asymp.LCL, ymax=asymp.UCL), alpha=0.3) +

geom_line(aes(color=color)) +

dragon_fill() +

dragon_color() +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(0, 0, 0, 0.5)) +

labs(y='Probability of breathing fire', x='Body Length', color='Dragon Color', fill='Dragon Color', title='Effects of color and body length on fire-breathing') +

theme_allie()

If you wanted to change the breaks on your x-axis, change the labels of

the breaks, or adjust the limits, you can do that all with different

arguments inside the scale_x_continuous call.

Have you ever wondered how people get their x-axis labels on a slant? Here’s how:

1

p + theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, vjust = 0, hjust=0))

angle adjusts the angle (setting it to 90 would make the labels

perpendicular to the plot), and vjust and hjust move the labels

along the vertical and horizontal dimensions.

Themes

One of the most powerful ways to customize your plots beyond the ggplot

defaults is to play with different themes. Allie built her own (which is

next-level), but there are many really nice and elegant themes that can

really take your plot to the next level. Some are built into ggplot

(like theme_minimal() or theme_classic), but others come from

devoted packages. One of my favorites is theme_pubr(). Let’s see how

it changes our glmer() plot:

1

2

library(ggpubr)

p + theme_pubr()

If you don’t like the legend on top, you can adjust that very simply:

1

p + theme_pubr(legend='right')

To adjust the position of your legend, or really anything about the

plotting space that doesn’t have to do with geoms (so things like axes,

backgrounds, text size, etc.), you’ll pass a command to the theme()

function of ggplot. Something I can’t recommend highly enough is taking

time to learn about and play around with all the different arguments

that can be passed to theme(). That’s where the vast majority of

customization comes in!

An important note: the layering of arguments within a ggplot object does

indeed matter. Geoms get stacked on top of each other based on the order

they’re listed. So if you want to overlay a jitter on top of a bar plot,

you need to make sure geom_jitter comes after geom_col. Likewise

with theme arguments that aren’t included in the base ggplot2

package. If you specify, for example, theme_pubr(legend='right'), but

then add legend.position='center' in your theme() call that comes

after the theme_pubr() call, then your legend is going to be placed in

the location of the most recent call; in this example, it would be

centered. I’ve run into this with things like font styles before, and

endured a fair share of head-bashing before realizing what I was doing.

Please learn from my mistakes!

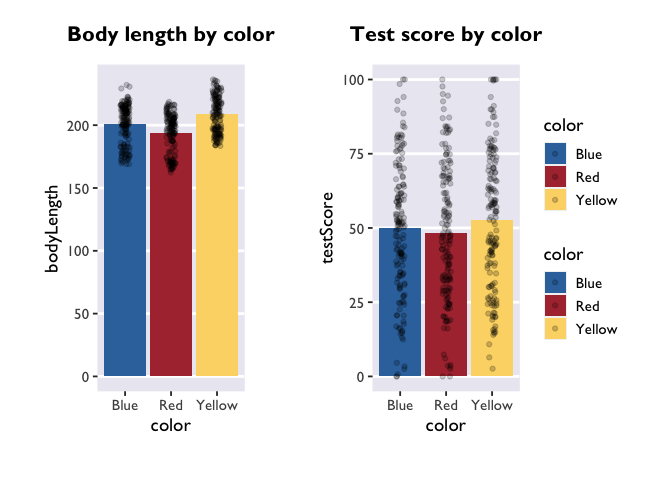

Writing a plotting function

Let’s say you have a plot style that you want to retain for a

number of different plots. Instead of copying and pasting the same lines

of code, you can simply write a function that defines all your plot

parameters and use that to generate a bunch of plots. Let’s step out of

the emmeans()-verse for a minute and look at how testScore and

bodyLength are related to color:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

dragon_plot <- function(yvar, title) {

ggplot(dragons, aes_(x=~color, y=yvar, fill=~color)) +

geom_bar(stat = "summary") +

geom_jitter(width = 0.1, height = 0, alpha = 0.2) +

ggtitle(title) +

scale_fill_dragon() +

theme_allie()

}

plot_bodyLength <- dragon_plot(~bodyLength, 'Body length by color')

plot_testScore <- dragon_plot(~testScore, 'Test score by color')

The important thing to note here is that you use aes_ instead of the

regular aes call, that the variables that you want to stay constant

across plots are preceded by a ~ when you define the function, and

that the variables you want to sub in are preceded by a ~ when you

call the function.

During the workshop, Kevin noted that you can use aes_string() instead

of aes_ and then substitute all the ~s for character strings.

Patchwork!

Let’s make these two plots into one figure using the awesome package

patchwork. This is another

package I can’t recommend enough. It uses the syntax of ggplot2 to

allow you to combine multiple plots into one figure. I won’t go into

details here, but you should definitely check out the (beautiful and

easy to use) website to learn more.

1

2

library(patchwork)

plot_bodyLength + plot_testScore + plot_layout(guides='collect')

1

2

# and if we wanted to export this figure as one single image, we would run:

#ggsave('filepath', dpi='retina')

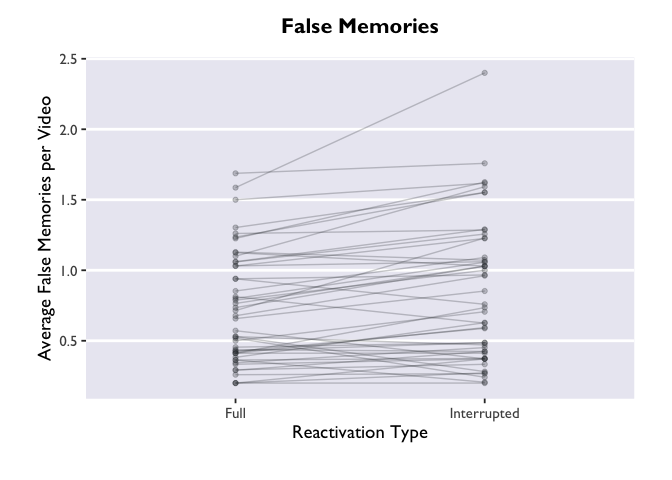

Spaghetti Plots

Next, let’s learn how to create spaghetti plots that connect the

dots for within-subjects measures. Unfortunately, we only measured our

dragons once (after all, they are hard to catch). So we’ll quickly load

one of Allie’s real datasets to look at some repeated measures.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

PE_recon <- read.csv("PE_recon.csv", fileEncoding="UTF-8-BOM")

PE_recon_sum <- summarySE(PE_recon, measurevar = "Errors_mean", groupvars = c("Group", "Type"))

ggplot(PE_recon, aes(x = Type, y = Errors_mean)) +

theme_allie() +

geom_point(aes(group=ID), color="#2b2e33", alpha = 0.25, size = 1.5) +

geom_line(aes(group=ID), color="#2b2e33", alpha = 0.25) +

xlab("Reactivation Type") +

ylab("Average False Memories per Video") +

ggtitle("False Memories")

The “group=ID” argument is doing the magic here. Try removing it

from the geom_point and geom_line layers, and see what happens. Not

pretty.

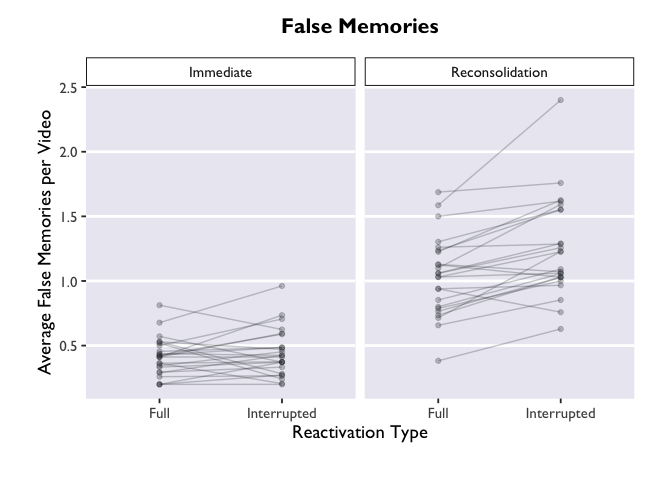

But wait! We actually have another grouping variable in

this dataset. This was a 2x2 design, where we had a between-subjects

contrast and a within-subjects contrast. Let’s create separate panels

for our between-subjects variable, Group.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

ggplot(PE_recon, aes(x = Type, y = Errors_mean)) +

theme_allie() +

geom_point(aes(group=ID), color="#2b2e33", alpha = 0.25, size = 1.5) +

geom_line(aes(group=ID), color="#2b2e33", alpha = 0.25) +

xlab("Reactivation Type") +

ylab("Average False Memories per Video") +

ggtitle("False Memories") +

facet_wrap(.~Group)

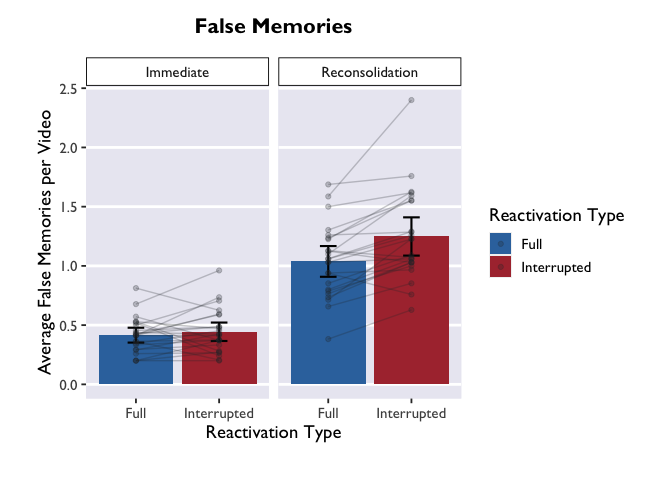

Much more informative, but this plot is still very bland. Let’s add

some bars to display the average for each condition, and give those bars

some color. We can add errorbars while we’re at it.

Note that we

are putting the geoms for the new bars BEFORE the geoms for the points

and lines. What happens if we move these geoms around? Try changing the

order to see how it affects the plot.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

ggplot(PE_recon, aes(x = Type, y = Errors_mean, fill = Type)) +

theme_allie() +

scale_fill_dragon(name = "Reactivation Type") +

scale_x_discrete(name = "Reactivation Type") +

geom_bar(stat = "summary", fun.y = "mean", na.action=na.omit) +

geom_errorbar(data = PE_recon_sum, aes(ymin = Errors_mean - ci, ymax = Errors_mean + ci), width=.2, size = 0.75, position=position_dodge(.9)) +

xlab("Reactivation Type") +

geom_point(aes(group=ID), color="#2b2e33", alpha = 0.25, size = 1.5) +

geom_line(aes(group=ID), color="#2b2e33", alpha = 0.25) +

ylab("Average False Memories per Video") +

ggtitle("False Memories") +

facet_wrap(. ~ Group)

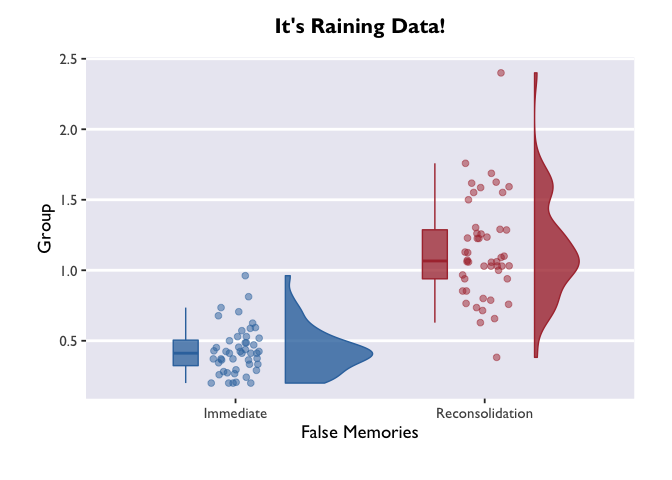

Raincloud Plots

In the final section, we’ll use our new layering skills to create a

raincloud plot! These are pretty plots that display the distribution of

your data, as well as the summary metrics for comparison.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

#we'll borrow this function that allows us to plot half violin plots

source("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/datavizpyr/data/master/half_flat_violinplot.R", local = knitr::knit_global())

#this is the same as the palette we generated earlier, but we need to specify it for COLOR instead of FILL (allowing us to apply it to dots in addition to bars)

scale_color_dragon <- function(...){

library(scales)

discrete_scale("color","dragon",manual_pal(values = c("#3574AC","#AD343C","#FBD774")), ...)

}

#think through what each of these layers adds to the plot. try turning them off and on!

#try enabling or disabling coord_flip() to change the orientation.

ggplot(data = PE_recon, aes(x = Group, y = Errors_mean, fill = Group, color = Group)) +

theme_allie() +

geom_flat_violin(position = position_nudge(x = .2, y = 0), alpha = .8, width = 0.7) +

geom_jitter(width = 0.1, height = 0, size = 2, alpha = 0.5) +

geom_boxplot(width = .1, alpha = 0.75, position = position_nudge(x = -.2, y = 0), outlier.shape = NA) +

scale_fill_dragon() +

scale_color_dragon() +

guides(fill = FALSE) +

guides(color = FALSE) +

#coord_flip() +

xlab("False Memories") +

ylab("Group") +

ggtitle("It's Raining Data!")

If we call ggplot() without specifying any variables, it just generates a blank square! This is actually the bottom layer of every plot. It’s a blank slate, waiting for us to layer data on top.

Let’s say our first research question is whether the color of the dragon is related to its intelligence. What happens when we specify those variables, but don’t add any geoms? We initialize a grid and axes, but don’t actually plot any data.

1

ggplot(data = dragons, aes(x = color, y = breathesFire))

1

2

# if we wanted to save the plot in our current working directory, we could run the line below.

#ggsave("dragon_color.png", dpi = 300, width = 4, height = 4, units = "in")

The biggest difference between plotting in the emmeans-verse and in

the way Allie showed above is that your y variable will almost always be

“emmean” and you don’t have to compute confidence intervals yourself.

But if you want to add information about the raw data (like the jitter

above), then you’ll need to add a layer that takes data from the source

dataframe. Note that you only need to specify the dimension on which

your variable is different from the one in the main ggplot call – i.e.,

I only had to specify y=testScore in the geom_jitter() call.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

ggplot(model_df, aes(x = color, y = emmean, fill = color)) +

scale_fill_dragon("Dragon Color") +

geom_col() +

geom_errorbar(aes(ymin=lower.CL, ymax=upper.CL), width = 0.4, size = 1) +

geom_jitter(data=dragons, aes(y=testScore), width = 0.1, height = 0, alpha = 0.2) +

xlab("Dragon Color") +

ylab("Cognitive Test Score") +

ggtitle("Test Score by Color") +

theme_allie()

Three things to note: first, we indicate that we want to extract

marginal means for the main terms and interactions with the | operator

(did you know it’s called a ‘pipe’??? TIL!). The * operator will do

exactly the same thing, and it has the added benefit of being more

similar to lmer syntax.

Second, we made another Stroop plot! The colors of the geoms don’t match the color names, and we no longer have Allie’s beautiful colors. Unfortunately, this shows the limits of custom color palettes – since they’re hard-coded, they need to have enough colors to cover all the different combinations of your discrete variables. So if you wanted to make an interaction plot like this with the same colors as Allie’s, you’d need to make another palette that has 9 values instead of 3.

Third, we have two legends! One where the geoms are colored and another

where they are black. This highlights the difference between the color

and fill arguments. Color is used to set the color of line-based

objects, like the outline of a bar, violin, ribbon, etc. It’s also used

to set the color of points. Given that our geom is a combination of

point & line, it’s only going to be modifiable by color arguments.

Fill is used to “fill in” empty spaces, like the inside of a column,

ribbon, or violin. Since we don’t have any geoms that take the fill

argument in this plot, then it just shows up as black. Getting rid of

fill=color and scale_fill_dragon() will get rid of the superfluous

legend.

Cool! The trends are still there, but now we have a more detailed depiction of how the probability of fire-breathing changes as a function of body length.

emmeans

is an immensely useful companion package for lme4 and lmerTest. The

vignettes on the page linked here are very helpful, and can be quite

illuminating about all the things you can do with fitted mixed models. I

highly recommend playing around with it to build up your knowledge about

mixed models!

And once you get familiar with emmeans & lmer, you can take the

fast-track to plotting model estimates:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

glmer(breathesFire ~ color*bodyLength + (1|mountainRange), data=dragons, family=binomial(link = "logit")) %>%

emmeans(., ~ color*bodyLength, type='response', at=list(bodyLength=bodyLength_range('bodyLength'))) %>%

as.data.frame() %>%

ggplot(., aes(x=bodyLength, y=prob,fill=color)) +

geom_ribbon(aes(ymin=asymp.LCL, ymax=asymp.UCL), alpha=0.3) +

geom_line(aes(color=color)) +

scale_fill_dragon("Dragon Color") +

scale_color_manual(values=c("#3574AC","#AD343C","#FBD774")) +

labs(y='Probability of breathing fire', x='Body Length', color='Dragon Color',title='Effects of color and body length on fire-breathing') +

theme_allie()

1

2

3

# create the palette

dragon_fill <- get_scale_fill(get_pal(dragon_colors))

dragon_color <- get_scale_color(get_pal(dragon_colors))

angle adjusts the angle (setting it to 90 would make the labels

perpendicular to the plot), and vjust and hjust move the labels

along the vertical and horizontal dimensions.

If you don’t like the legend on top, you can adjust that very simply:

1

p + theme_pubr(legend='right')

To adjust the position of your legend, or really anything about the

plotting space that doesn’t have to do with geoms (so things like axes,

backgrounds, text size, etc.), you’ll pass a command to the theme()

function of ggplot. Something I can’t recommend highly enough is taking

time to learn about and play around with all the different arguments

that can be passed to theme(). That’s where the vast majority of

customization comes in!

An important note: the layering of arguments within a ggplot object does

indeed matter. Geoms get stacked on top of each other based on the order

they’re listed. So if you want to overlay a jitter on top of a bar plot,

you need to make sure geom_jitter comes after geom_col. Likewise

with theme arguments that aren’t included in the base ggplot2

package. If you specify, for example, theme_pubr(legend='right'), but

then add legend.position='center' in your theme() call that comes

after the theme_pubr() call, then your legend is going to be placed in

the location of the most recent call; in this example, it would be

centered. I’ve run into this with things like font styles before, and

endured a fair share of head-bashing before realizing what I was doing.

Please learn from my mistakes!

Writing a plotting function

1

2

# and if we wanted to export this figure as one single image, we would run:

#ggsave('filepath', dpi='retina')