Intro to Probabilistic Programming with Stan

In this tutorial we’re going to talk about what probabilistic programming is and how we can use it for statistical modeling. If you aren’t familiar at all with Bayesian stats, check out my previous post on the topic. If you’re used to probabilistic programming but just want to learn the Stan language, you can go straight to the fantastic Stan User’s Guide, which explains how to program a wide variety of models.

- What is probabilistic programming?

- Probabilistic programming with Stan

- Assessing model convergence

- Assessing model fit

- Linear Regression in Stan

- Summary

What is probabilistic programming?

Probabilistic programming is a relatively new and exciting approach to statistical modeling that lets you create models in a standardized language without having to implement any of the nitty-gritty details or work out too much math. Although not all probabilistic programs are Bayesian, probabalistic programming makes Bayesian modeling easy, and so it’s a great way to learn what Bayesian models are, how they’re fit to data, and what you can do with them. To explain what probabilistic programming is, I’m going to use just a little bit of math. Bear with me, because this is important!

In Bayesian statistics, we start with a model and some data. As a simple example, we might model some ratings on a scale using a normal distribution with a particular mean μ and variance σ2 . Our goal is to identify the most likely parameter values given our data (that is, the values of μ and σ that best explain our data). To determine which which parameter values are best, we make use of Bayes’ formula:

P(θ|𝒟) ∝ P(θ)P(𝒟|θ)

This formula says that the probability of a parameter value θ given our data 𝒟 is proportional to our prior probability of that parameter value multiplied by the likelihood that the data could have been generated from that parameter value. How do we determine the likelihood? Well, sometimes we can derive the likelihood (and hence the posterior) by hand. But in most cases, this approach is too difficult or time-consuming. In probabilistic programming, we write a program that simulates our model given some parameter values. This is actually useful in its own right: we can use this program to see how the model behaves under different settings of the parameters. But in statistical inference, the important part is that we run that program to (approximately) calculate the likelihood, which in turn lets us calculate the posterior probability of the parameter values given our data.

Why Stan?

There are a good number of probabilistic programming languages out

there. Today we’re going to focus on Stan, which

is one of the fastest, most reliable, and most widely used probabilistic

programming languages out there. One of the cool things about Stan is

that there are a number of different interfactes to Stan: you can use

Stan through R, through Python, through Matlab, through Julia, and even

directly through the command-line! If you’ve read my tutorial on

Bayesian regression with

brms, then you’ve

actually already used one of the easiest interfaces to Stan, which

writes Stan programs for you based on lmer-like formulas. Lastly, Stan

has one of the largest communities

that makes getting coding help and statistical advice easy.

The components of a Stan program

Unsurprisingly, Stan programs are written in Stan files, which use the

extension .stan. The Stan language has similar syntax to C++, in

that it uses curly braces ({ and }) to define blocks of code,

semicolons (;) after each statement, and has a type declaration for

every variable in the program. There are two primitive data types: int

for integers, and real for floating-point/decimal numbers. There are

also a few different container types: array, vector, and

row_vector for one-dimensional containers, and matrix for

N-dimensional containers. For now, the differences between array,

vector, and row_vector aren’t that important. Just know that when

possible, we will try to use type vector, which will generally be most

efficient.

Stan programs consist of up to seven different blocks of code, in the following order (*required):

functionsdata*transformed dataparameters*transformed parametersmodel*generated quantities

In the remainder of the workshop, we’re going to focus on the data,

parameters, model, and generated_quantities blocks, but we’ll also

use the transformed parameters block.

Probabilistic programming with Stan

To demonstrate the power of Stan, let’s first get a nice dataset to work with. Here I’m going to load some packages, and then run some code to gather data from the Spotify top 200 songs per week in 2021. Don’t worry about how this code actually works (we can save that for a future meeting…), but know that it will take some time (~5mins) if you run this on your computer.

Getting some data

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

library(cmdstanr) # for stan

library(tidyverse) # for data wrangling

library(lubridate) # for dates

library(rvest) # for scraping spotify charts

library(spotifyr) # for spotify audio features

library(tidybayes) # for accessing model posteriors

library(viridis) # for pretty plots

options(mc.cores=parallel::detectCores())

## gather spotify chart data (modified from https://rpubs.com/argdata/web_scraping)

scrape_spotify <- function(url) {

page <- url %>% read_html() # read the HTML page

rank <- page %>%

html_elements('.chart-table-position') %>%

html_text() %>%

as.integer

track <- page %>%

html_elements('strong') %>%

html_text()

artist <- page %>%

html_elements('.chart-table-track span') %>%

html_text() %>%

str_remove('by ')

streams <- page %>%

html_elements('td.chart-table-streams') %>%

html_text() %>%

str_remove_all(',') %>%

as.integer

URI <- page %>%

html_elements('a') %>%

html_attr('href') %>%

str_subset('https://open.spotify.com/track/') %>%

str_remove('https://open.spotify.com/track/')

## combine, name, and make it a tibble

chart <- tibble(rank=rank, track=track, artist=artist, streams=streams, URI=URI)

return(chart)

}

## setup access to Spotify API

access_token <- get_spotify_access_token()

## load the top 200 songs in the US per week in 2021

spotify2021 <- tibble(week=seq(ymd('2021-01-01'), ymd('2021-11-19'), by = 'weeks')) %>%

mutate(url=paste0('https://spotifycharts.com/regional/us/weekly/', week, '--', week+days(7)),

data=map(url, scrape_spotify)) %>%

unnest(data) %>%

mutate(streams=streams/1000000)

## extract spotify's audio features for each song

features <- tibble(URI=unique(spotify2021$URI)) %>%

mutate(features=map(URI, ~ get_track_audio_features(.x, authorization=access_token))) %>%

unnest(features)

## make one tidy data frame

spotify2021 <- spotify2021 %>% left_join(features, by='URI') %>%

select(-URI, -analysis_url, -track_href, -id, -type) %>%

relocate(week, rank, track, artist, streams, duration_ms, tempo,

time_signature, key, mode, valence, loudness, danceability,

energy, speechiness, acousticness, instrumentalness, liveness, uri, url)

write_csv(spotify2021, '2021-12-10-spotify-data.csv')

spotify2021

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

## # A tibble: 9,400 × 20

## week rank track artist streams duration_ms tempo time_signature key

## <date> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 2021-01-01 1 Good … SZA 6.32 279204 121. 4 1

## 2 2021-01-01 2 Anyone Justi… 6.15 190779 116. 4 2

## 3 2021-01-01 3 34+35 Arian… 5.61 173711 110. 4 0

## 4 2021-01-01 4 Mood … 24kGo… 5.58 140526 91.0 4 7

## 5 2021-01-01 5 Lemon… Inter… 5.37 195429 140. 4 1

## 6 2021-01-01 6 DÁKITI Bad B… 5.16 205090 110. 4 4

## 7 2021-01-01 7 posit… Arian… 5.10 172325 144. 4 0

## 8 2021-01-01 8 Whoop… CJ 4.88 123263 140. 4 3

## 9 2021-01-01 9 WITHO… The K… 4.78 161385 93.0 4 0

## 10 2021-01-01 10 Blind… The W… 4.44 200040 171. 4 1

## # … with 9,390 more rows, and 11 more variables: mode <dbl>, valence <dbl>,

## # loudness <dbl>, danceability <dbl>, energy <dbl>, speechiness <dbl>,

## # acousticness <dbl>, instrumentalness <dbl>, liveness <dbl>, uri <chr>,

## # url <chr>

As we can see, we now have a dataframe of Spotify’s weekly top 200 tracks, along with the following information:

week: the week in 2021rank: the song’s rank (1to200) in this week, with1being the top songtrack: the name of the songartist: the name of the artist who released the songstreams: the number of streams in that week (in millions)duration_ms: the duration of the track in mstempo: the tempo of the track in beats per minutetime_signature: an estimated time signature ranging from3to7(for 3/4 to 7/4)key: the key of the song from0(for C) to11(for B), or-1if no key was foundmode: whether the track is in a major (1) or minor (0) keyvalence: the emotional valence of the track from0(negative valence/sad) to1(positive valence/happy)loudness: the average loudness of the track in decibelsdanceability: an estimate of how danceable the track is, from0(least danceable) to1(most danceable)energy: an estimate of the intensity or activity of the track, from0(low energy) to1(high energy)speechiness: an estimate of the proportion of speech in the track, from0(no speech) to1(only speech)acousticness: an estimate of the degree to which a track is (1) or is not (0) acousticinstrumentalness: an estimate of the degree to which a track contains (1) or does not contain (0) vocalsliveness: an estimate of whether the track was performed live (1) or not (0)uri: the Spotify unique identifier for the trackurl: a link to the track

Simulating fake data: number of streams

Let’s say we want to know how many times, on average, the top 200 tracks

are streamed every week. Of course, we could just use

mean(spotify2021$streams) to get this number, but to get more

information we will need to specify a model. As a start, we can assume a

normal distribution with mean

μ

and standard deviation

σ

. Before fitting this model, we might just want to know what data

simulated from this model looks like under different parameter values.

This is the main goal of simulation: we assume that we know what the

values of

μ

and

σ

are to check what the distribution of streams would look like if those

values were true. To do that, let’s write a Stan program, which I’ll

save in the file 2021-12-10-streams-sim.stan:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

data {

real<lower=0> mu; // the mean

real<lower=0> sigma; // the standard deviation

}

parameters {

}

model {

}

generated quantities {

// simulate data using a normal distribution

real y_hat = normal_rng(mu, sigma);

}

Since we’re simulating from a prior, we will take our parameters mu

and sigma as inputs to Stan by declaring them in the data block. The

code real<lower=0> mu; defines a variable called mu that will refer

to the mean of the number of streams, and similarly

real<lower=0> sigma; defines the standard deviation. Both of these

variables are lower-bounded at 0 with the expression <lower=0>,

because it wouldn’t make sense to simulate a negative number of streams

or a negative standard deviation (we would also put an upper bound here

if it made sense). Since our model has no remaining parameters, and we

are not yet modeling any data, both the parameters and model blocks

are empty. Finally, in the generated quantities block, we are telling

our model to simulate the number of streams by drawing a random number

from a normal distribution.

To run our Stan program, we will make use of the library cmdstanr. The

rstan library also works for this, but I’ve found cmdstanr to be

faster and more reliable. Let’s say we know that there are roughly one

million streams per week, but this varies with a standard deviation of

one hundred thousand streams. We can make a list of these values, and

pass them to Stan as data:

1

2

3

streams_sim_data <- list(mu=1, sigma=.1)

streams_sim_model <- cmdstan_model('2021-12-10-streams-sim.stan') ## compile the model

streams_sim <- streams_sim_model$sample(data=streams_sim_data, fixed_param=TRUE)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

## Running MCMC with 4 chains, at most 20 in parallel...

##

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1 / 1000 [ 0%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 100 / 1000 [ 10%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 200 / 1000 [ 20%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 300 / 1000 [ 30%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 400 / 1000 [ 40%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 500 / 1000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 600 / 1000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 700 / 1000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 800 / 1000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 900 / 1000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1000 / 1000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1 / 1000 [ 0%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 100 / 1000 [ 10%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 200 / 1000 [ 20%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 300 / 1000 [ 30%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 400 / 1000 [ 40%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 500 / 1000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 600 / 1000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 700 / 1000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 800 / 1000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 900 / 1000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1000 / 1000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1 / 1000 [ 0%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 100 / 1000 [ 10%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 200 / 1000 [ 20%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 300 / 1000 [ 30%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 400 / 1000 [ 40%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 500 / 1000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 600 / 1000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 700 / 1000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 800 / 1000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 900 / 1000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1000 / 1000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1 / 1000 [ 0%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 100 / 1000 [ 10%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 200 / 1000 [ 20%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 300 / 1000 [ 30%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 400 / 1000 [ 40%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 500 / 1000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 600 / 1000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 700 / 1000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 800 / 1000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 900 / 1000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1000 / 1000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 finished in 0.0 seconds.

## Chain 2 finished in 0.0 seconds.

## Chain 3 finished in 0.0 seconds.

## Chain 4 finished in 0.0 seconds.

##

## All 4 chains finished successfully.

## Mean chain execution time: 0.0 seconds.

## Total execution time: 0.3 seconds.

As we can see, the model has simulated 1000 stream counts in four

different chains. Note that above, we used the argument

fixed_param=TRUE to tell Stan that our model has no parameters, which

makes the sampling faster. Let’s look at a summary of our model:

1

streams_sim

1

2

## variable mean median sd mad q5 q95 rhat ess_bulk ess_tail

## y_hat 1.00 1.00 0.10 0.10 0.83 1.17 1.00 3848 3898

This summary tells us that our simulated streams counts have an average

of about one million and a standard deviation of about one hundred

thousand. To access the simulated data, we have a few different options.

Within cmdstanr, the default is to use streams_sim$draws(). However,

I find that the spread_draws function from tidybayes is usually

easier to work with, as it gives us a nice tidy dataframe of whatever

variables we want. The other reason is that we’re going to use

tidybayes (technically ggdist) to make pretty plots of our draws.

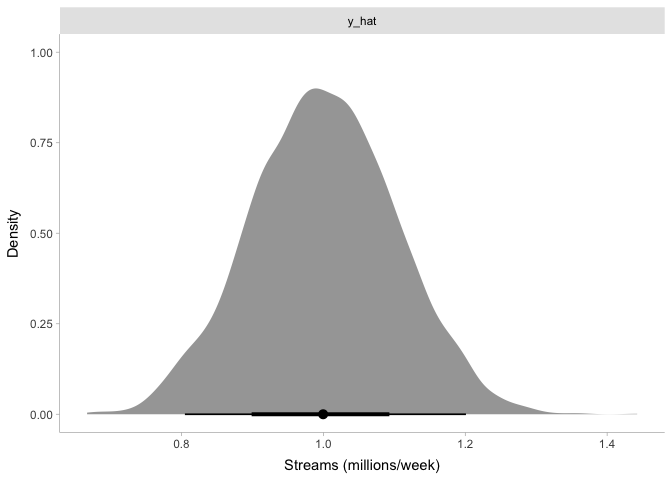

Let’s get our draws and plot them:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

draws <- streams_sim %>% gather_draws(y_hat)

ggplot(draws, aes(x=.value)) +

stat_halfeye(point_interval=median_hdi, normalize='panels') +

xlab('Streams (millions/week)') + ylab('Density') +

facet_wrap(~ .variable, scales='free') +

theme_tidybayes()

Again, this tells us what we already expected: our simulated top 200 songs have somewhere around one million streams per week, and the number of streams are normally distributed around that.

Sampling from a prior distribution

It’s nice to simulate data, but of course our main goal is to infer what

the actual mean and standard deviation of stream counts for the top

200 tracks. To do so, we first need to define a prior distribution.

Thankfully, this is pretty easy in Stan: we just move the parameters

mu and sigma from the data block to the parameters block:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

data {

}

parameters {

real<lower=0> mu; // the mean

real<lower=0> sigma; // the standard deviation

}

model {

// define priors for mu and sigma

mu ~ normal(1, .1);

sigma ~ normal(0, .1);

}

generated quantities {

// simulate data using a normal distribution

real y_hat = normal_rng(mu, sigma);

}

Besides the declarations of mu and sigma being moved to the

parameters block, we can see that we’ve also added to the model

block. Specifically, the model block now specifies prior distributions

over our two parameters. The symbol ~ can be read as “is distributed

as”, so we’re saying that mu is distributed according to a normal

distribution with a mean of one million and a standard deviation of one

hundred thousand. Likewise, we’re assuming that sigma is distributed

normally around 0 with a standard deviation of one hundred thousand. You

might think that this would give us negative numbers, but Stan truncates

these normal distributions at 0 because of the <lower=0> in the

paramters’ declarations. Now let’s sample from our prior distribution to

simulate some fake data:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

streams_prior_model <- cmdstan_model('2021-12-10-streams-prior.stan') ## compile the model

streams_prior <- streams_prior_model$sample()

streams_prior

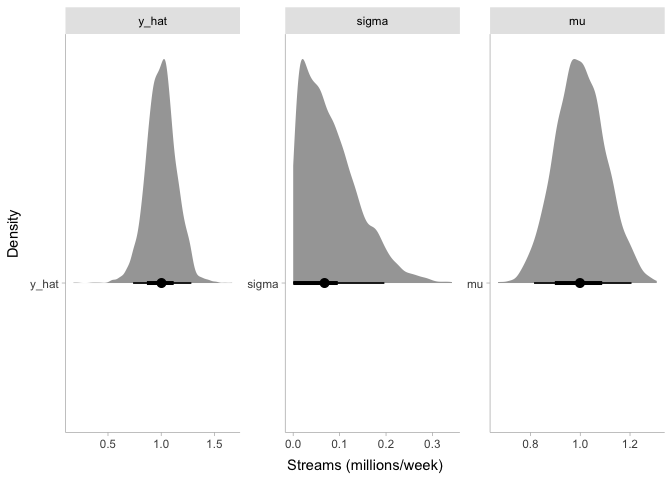

streams_prior %>%

gather_draws(mu, sigma, y_hat) %>%

mutate(.variable=factor(.variable, levels=c('y_hat', 'sigma', 'mu'))) %>%

ggplot(aes(x=.value, y=.variable)) +

stat_halfeye(point_interval=median_hdi, normalize='panels') +

xlab('Streams (millions/week)') + ylab('Density') +

facet_wrap(~ .variable, scales='free') +

theme_tidybayes()

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

## Running MCMC with 4 chains, at most 20 in parallel...

##

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 100 / 2000 [ 5%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 300 / 2000 [ 15%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 500 / 2000 [ 25%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 700 / 2000 [ 35%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 900 / 2000 [ 45%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1100 / 2000 [ 55%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1300 / 2000 [ 65%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1500 / 2000 [ 75%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1700 / 2000 [ 85%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1900 / 2000 [ 95%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 100 / 2000 [ 5%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 300 / 2000 [ 15%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 500 / 2000 [ 25%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 700 / 2000 [ 35%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 900 / 2000 [ 45%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1100 / 2000 [ 55%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1300 / 2000 [ 65%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1500 / 2000 [ 75%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1700 / 2000 [ 85%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1900 / 2000 [ 95%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 100 / 2000 [ 5%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 300 / 2000 [ 15%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 500 / 2000 [ 25%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 700 / 2000 [ 35%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 900 / 2000 [ 45%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1100 / 2000 [ 55%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1300 / 2000 [ 65%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1500 / 2000 [ 75%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1700 / 2000 [ 85%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1900 / 2000 [ 95%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 100 / 2000 [ 5%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 300 / 2000 [ 15%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 500 / 2000 [ 25%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 700 / 2000 [ 35%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 900 / 2000 [ 45%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1100 / 2000 [ 55%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1300 / 2000 [ 65%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1500 / 2000 [ 75%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1700 / 2000 [ 85%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1900 / 2000 [ 95%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 finished in 0.0 seconds.

## Chain 2 finished in 0.0 seconds.

## Chain 3 finished in 0.0 seconds.

## Chain 4 finished in 0.0 seconds.

##

## All 4 chains finished successfully.

## Mean chain execution time: 0.0 seconds.

## Total execution time: 0.2 seconds.

## variable mean median sd mad q5 q95 rhat ess_bulk ess_tail

## lp__ -3.94 -3.61 1.08 0.83 -6.10 -2.85 1.00 1430 1617

## mu 1.00 1.00 0.10 0.10 0.84 1.17 1.00 1960 1705

## sigma 0.08 0.07 0.06 0.06 0.01 0.20 1.00 1391 1210

## y_hat 1.00 1.00 0.14 0.13 0.78 1.24 1.00 2721 2915

Just like before, we now have simulated values of y_hat centered

around one million streams per week. However, the distribution of

y_hat is wider than before. When we simulated stream counts with a

fixed mu and sigma, the only source of noise in our simulated data

was the noise in the sampling process. But now that we have included

mu and sigma as parameters in the model, we also have uncertainty in

mu and sigma that creates some more noise in y_hat.

Fitting a model to data

You might have noticed that that was a whole lot of work to go through

to sample from some normal distributions. Up until now, we could have

just as well used rnorm a few times to do the trick. So what’s the

point? Well, using (almost) the same Stan code, we can now fit this

simple model to our data to find the most likely values of

μ

and

σ

:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

data {

int<lower=0> N; // the number of data points

vector<lower=0>[N] y; // the data to model

}

parameters {

real<lower=0> mu; // the mean

real<lower=0> sigma; // the standard deviation

}

model {

// define priors for mu and sigma

mu ~ normal(1, .1);

sigma ~ normal(0, .1);

// define the likelihood of y

y ~ normal(mu, sigma);

}

generated quantities {

// simulate data using a normal distribution

real y_hat = normal_rng(mu, sigma);

}

Compared to the previous code, we have added two things. First, in the

data block, we added declarations for two variables. y is a vector

containing the stream counts for each track in each week. The syntax

[N] tells Stan that this vector is N numbers long, which is why we

also declared a data variable N. Finally, in the model block, we

added a line that defines the likelihood of y given our model: we are

modeling y as normally-distributed with mean mu and standard

deviation sigma. Rather than just evaluating the likelihood of the

data according to our prior distributions, Stan will sample the values

of mu and sigma according to their posterior probability using

Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), giving us an approximate posterior

distribution. Let’s run it and see what happens:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

streams_data <- list(N=nrow(spotify2021), y=spotify2021$streams)

streams_model <- cmdstan_model('2021-12-10-streams.stan') ## compile the model

streams <- streams_model$sample(data=streams_data, save_warmup=TRUE)

streams

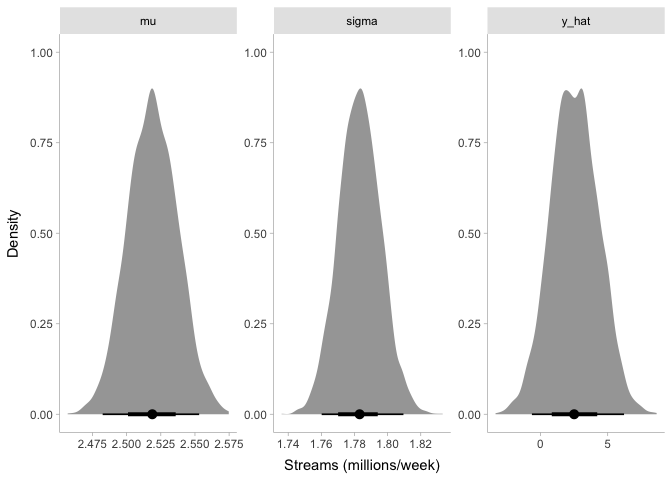

draws <- streams %>% gather_draws(mu, sigma, y_hat)

ggplot(draws, aes(x=.value)) +

stat_halfeye(point_interval=median_hdi, normalize='panels') +

xlab('Streams (millions/week)') + ylab('Density') +

facet_wrap(~ .variable, scales='free') +

theme_tidybayes()

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

## Running MCMC with 4 chains, at most 20 in parallel...

##

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 100 / 2000 [ 5%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 300 / 2000 [ 15%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 500 / 2000 [ 25%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 700 / 2000 [ 35%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 900 / 2000 [ 45%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1100 / 2000 [ 55%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 100 / 2000 [ 5%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 300 / 2000 [ 15%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 500 / 2000 [ 25%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 700 / 2000 [ 35%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 900 / 2000 [ 45%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1100 / 2000 [ 55%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1300 / 2000 [ 65%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1500 / 2000 [ 75%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1700 / 2000 [ 85%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1900 / 2000 [ 95%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 100 / 2000 [ 5%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 300 / 2000 [ 15%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 500 / 2000 [ 25%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 700 / 2000 [ 35%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 900 / 2000 [ 45%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1100 / 2000 [ 55%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1300 / 2000 [ 65%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1500 / 2000 [ 75%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1700 / 2000 [ 85%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1900 / 2000 [ 95%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 100 / 2000 [ 5%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 300 / 2000 [ 15%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 500 / 2000 [ 25%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 700 / 2000 [ 35%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 900 / 2000 [ 45%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1100 / 2000 [ 55%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1300 / 2000 [ 65%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1500 / 2000 [ 75%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1700 / 2000 [ 85%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1900 / 2000 [ 95%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1300 / 2000 [ 65%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1500 / 2000 [ 75%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1700 / 2000 [ 85%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1900 / 2000 [ 95%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 finished in 0.2 seconds.

## Chain 2 finished in 0.2 seconds.

## Chain 3 finished in 0.2 seconds.

## Chain 4 finished in 0.2 seconds.

##

## All 4 chains finished successfully.

## Mean chain execution time: 0.2 seconds.

## Total execution time: 0.8 seconds.

## variable mean median sd mad q5 q95 rhat ess_bulk

## lp__ -10568.72 -10568.40 0.97 0.74 -10570.60 -10567.80 1.00 1861

## mu 2.52 2.52 0.02 0.02 2.49 2.55 1.00 3421

## sigma 1.78 1.78 0.01 0.01 1.76 1.80 1.00 3618

## y_hat 2.54 2.51 1.76 1.77 -0.32 5.41 1.00 4011

## ess_tail

## 2564

## 2786

## 2641

## 3889

Even though our prior for mu was around one million streams per week,

it looks like our posterior is now around 2.5 million streams per week.

Likewise, the posterior for sigma is about 1.8 million, even though

our prior was centered around 0. Finally, looking at y_hat, it appears

that our model estimates the number of streams per week to be anywhere

from -500,000 to 5.5 million. Before we talk about these results any

further, though, let’s make sure that we can trust them.

Assessing model convergence

Since we don’t have direct access to the posterior distribution, Stan

uses Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) to sample values of mu and

sigma. We won’t go into the details here, but the gist is that MCMC

approximates the posterior distributions over mu and sigma by trying

to sample their values in proportion to their posterior probability. If

the samples look like they have come from the posterior distribution, we

say the model has converged. If not, we cannot use the sampled values

for inference, because they don’t reflect our posterior.

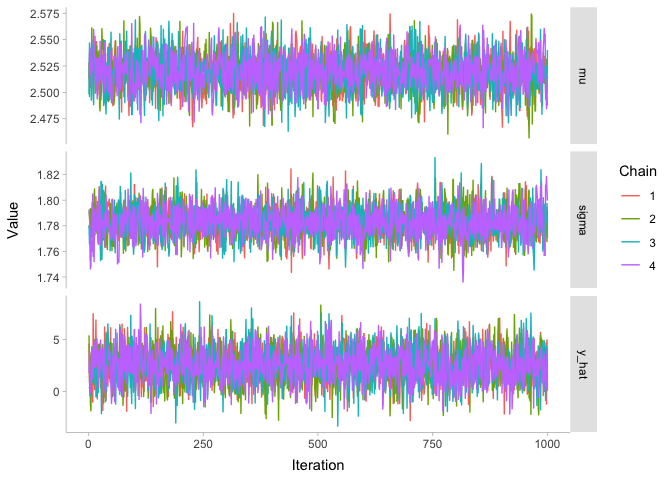

The fuzzy caterpillar check

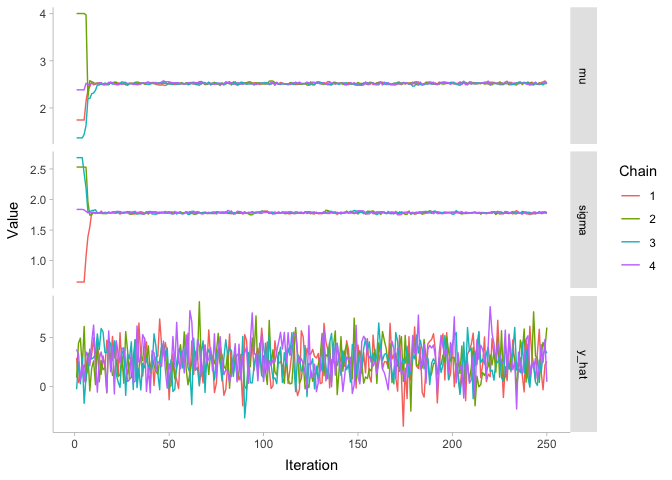

There are few different metrics for assessing convergence of MCMC chains. Honestly, the best one is visual: the “fuzzy caterpillar” check. The idea is you plot the MCMC chains for each parameter as a function of iteration number, like so:

1

2

3

4

5

ggplot(draws, aes(x=.iteration, y=.value, color=factor(.chain))) +

geom_line() + xlab('Iteration') + ylab('Value') +

scale_color_discrete(name='Chain') +

facet_grid(.variable ~ ., scales='free_y') +

theme_tidybayes()

Since all of these chains look like nice fuzzy caterpillars, we can be pretty confident that they converged. To demonstrate what the chains would look like if they hadn’t converged, let’s look at the chains before the warmup period. The warmup period is the first stage of the model while it is assumed to still be converging: typically we say that something like the first half of the samples are in the warmup period, and we throw them away to be left with just the good stuff.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

streams$draws(variables=c('mu', 'sigma', 'y_hat'),

inc_warmup=TRUE, format='draws_df') %>%

pivot_longer(mu:y_hat, names_to='.variable', values_to='.value') %>%

filter(.iteration <= 250) %>%

ggplot(aes(x=.iteration, y=.value, color=factor(.chain))) +

geom_line() + xlab('Iteration') + ylab('Value') +

scale_color_discrete(name='Chain') +

facet_grid(.variable ~ ., scales='free_y') +

theme_tidybayes()

As we can see, the first 25 or so iterations do not look like nice fuzzy caterpillars. Instead, we can tell all of the four chains apart from each other, since they are close to their random initializaiton values. But by iteration 50, it appears that our model has converged: the parameters have all ended up around the values of our posterior distribution.

R-hat

If the qualitative visual check isn’t working for you, you might want something a bit more quantitative. One option is R-hat, which is the ratio of the between-chain variance and the within-chain variance of the parameter values. This gives us a good quantification of the fuzzy caterpillar check: if the between-chain variance is high (relative to the within-chain variance), the chains are all exploring different regions of the parameter space and don’t overlap much. On the other hand, if the two variances are about equal, then the chains should look like fuzzy caterpillars. Typically we look for R-hat values to be as close to 1 as possible and we start to be suspicious of poor convergence if R-hat > 1.05.

1

streams$summary() %>% select(variable, rhat)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

## # A tibble: 4 × 2

## variable rhat

## <chr> <dbl>

## 1 lp__ 1.00

## 2 mu 1.00

## 3 sigma 1.00

## 4 y_hat 1.00

Since our R-hat values are all 1.00, our model looks pretty good.

Effective Sample Size (ESS)

Related to R-hat, we can also look at the effective sample size (ESS) of

the model. Recall that we sampled 1000 draws from four MCMC chains,

resulting in 4000 total samples from the posterior. In an ideal scenario

where every iteration of the model is totally independent of the

previous iteration, this would mean that we have a sample size of 4000

samples. But most of the time, there is some amount of auto-correlation

of the parameter values between iterations. To account for this, ESS is

the sample size adjusted for within-chain auto-correlation. In other

words, even though we have 4000 samples from the posterior, because of

auto-correlation inherent in the model fitting process, we effectively

have fewer independent samples. cmdstanr actually gives us two

different ESSs: a bulk ESS and a tail ESS. The bulk ESS tells us the

effective sample size for our estimates of central tendency (i.e.,

mean/median), and the tail ESS tells us the effective sample size for

our estimates of the tail quantiles and credible intervals. Since there

are fewer samples at the tails, we will typically have a lower tail ESS

than bulk ESS. In any case, you want all of these ESSs to be as large as

possible. Minimally, it is good to have an ESS of 1000 for practical

applications.

1

streams$summary() %>% select(variable, ess_bulk, ess_tail)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

## # A tibble: 4 × 3

## variable ess_bulk ess_tail

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 lp__ 1862. 2564.

## 2 mu 3422. 2787.

## 3 sigma 3619. 2641.

## 4 y_hat 4012. 3890.

Our bulk ESS looks very good- all of the values are close to 4000. Though the tail ESS is lower, it is still acceptable.

Assessing model fit

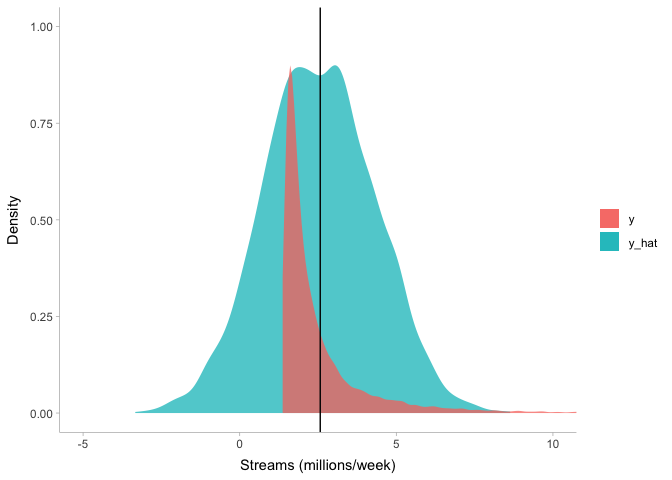

Now that we know that our model converged, let’s try to figure out how well it fit. In other words, how well does our model describe the data? Just as the fuzzy-caterpillar check provides a quick & easy way of assessing convergence, posterior predictive checks do the same for model fit. To perform a posterior predictive check, all we have to do is plot the distribution of simulated data alongside the distribution of actual data:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

draws %>%

filter(.variable=='y_hat') %>%

ggplot(aes(x=.value, fill=.variable)) +

stat_slab(slab_alpha=.75) +

stat_slab(slab_alpha=.75, data=tibble(.variable='y', .value=spotify2021$streams)) +

geom_vline(xintercept=mean(spotify2021$streams)) +

scale_fill_discrete(name='') +

xlab('Streams (millions/week)') + ylab('Density') +

coord_cartesian(xlim=c(-5, 10)) +

theme_tidybayes()

We can see that even though our model captures the mean of the stream

counts (the black vertical line) very well, there are a few problems.

First and foremost, it predicts some negative stream counts. For the top

200 songs on Spotify, not only is a negative number of streams very

unlikely, it is also impossible. Second, it predicts that most stream

counts will be at the mean, but the data have a positive skew. Let’s try

to fix these two issues at once by using a log-normal distribution

instead of a Normal distribution. The log-normal distribution is simply

what you get when you exponentiate samples from the normal distribution:

lognormal(μ,σ) = exp(Normal(μ,σ))

. So let’s try this distribution out, adjusting our priors over mu and

sigma:

1

2

3

streams_model_lognormal <- cmdstan_model('2021-12-10-streams-lognormal.stan') ## compile the model

streams_lognormal <- streams_model_lognormal$sample(data=streams_data)

streams_lognormal

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

## Running MCMC with 4 chains, at most 20 in parallel...

##

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 100 / 2000 [ 5%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 300 / 2000 [ 15%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 100 / 2000 [ 5%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 300 / 2000 [ 15%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 500 / 2000 [ 25%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 700 / 2000 [ 35%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 900 / 2000 [ 45%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1100 / 2000 [ 55%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1300 / 2000 [ 65%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1500 / 2000 [ 75%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1700 / 2000 [ 85%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 100 / 2000 [ 5%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 300 / 2000 [ 15%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 500 / 2000 [ 25%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 700 / 2000 [ 35%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 900 / 2000 [ 45%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1100 / 2000 [ 55%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1300 / 2000 [ 65%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1500 / 2000 [ 75%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1700 / 2000 [ 85%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1900 / 2000 [ 95%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 100 / 2000 [ 5%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 300 / 2000 [ 15%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 500 / 2000 [ 25%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 700 / 2000 [ 35%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 900 / 2000 [ 45%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1100 / 2000 [ 55%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1300 / 2000 [ 65%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1500 / 2000 [ 75%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1700 / 2000 [ 85%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1900 / 2000 [ 95%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 500 / 2000 [ 25%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 700 / 2000 [ 35%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 900 / 2000 [ 45%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1100 / 2000 [ 55%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1300 / 2000 [ 65%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1500 / 2000 [ 75%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1700 / 2000 [ 85%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1900 / 2000 [ 95%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 finished in 0.5 seconds.

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1900 / 2000 [ 95%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 finished in 0.5 seconds.

## Chain 3 finished in 0.6 seconds.

## Chain 4 finished in 0.6 seconds.

##

## All 4 chains finished successfully.

## Mean chain execution time: 0.5 seconds.

## Total execution time: 1.1 seconds.

## variable mean median sd mad q5 q95 rhat ess_bulk ess_tail

## lp__ -5789.20 -5788.89 0.97 0.67 -5791.16 -5788.29 1.00 1990 2763

## mu 0.81 0.81 0.00 0.00 0.81 0.82 1.00 4259 3110

## sigma 0.45 0.45 0.00 0.00 0.44 0.45 1.00 3122 2651

## y_hat 2.51 2.28 1.20 0.97 1.08 4.77 1.00 3558 3888

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

streams_lognormal %>%

gather_draws(y_hat) %>%

ggplot(aes(x=.value, fill=.variable)) +

stat_slab(slab_alpha=.75, fill=NA, color='black', data=filter(draws, .variable=='y_hat') %>% mutate(.variable='y_hat (normal)')) +

stat_slab(slab_alpha=.75) +

stat_slab(slab_alpha=.75, data=tibble(.variable='y', .value=spotify2021$streams)) +

geom_vline(xintercept=mean(spotify2021$streams)) +

scale_fill_discrete(name='') +

xlab('Streams (millions/week)') + ylab('Density') +

coord_cartesian(xlim=c(-5, 10)) +

theme_tidybayes()

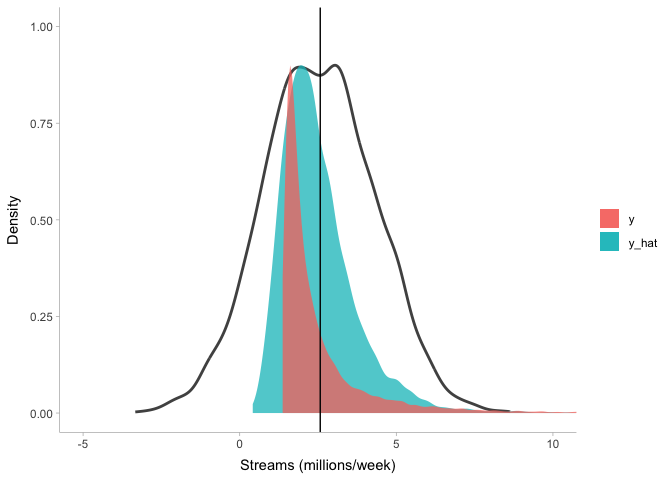

Clearly this model (blue) does a lot better at describing stream counts than the previous one (black line), but it’s not perfect either. Importantly, there is no single gold standard for model fit: a model that fits perfectly fine for some purposes may not be good for other purposes. So it is up to you, the modeler, to determine when your model is good enough to inspect.

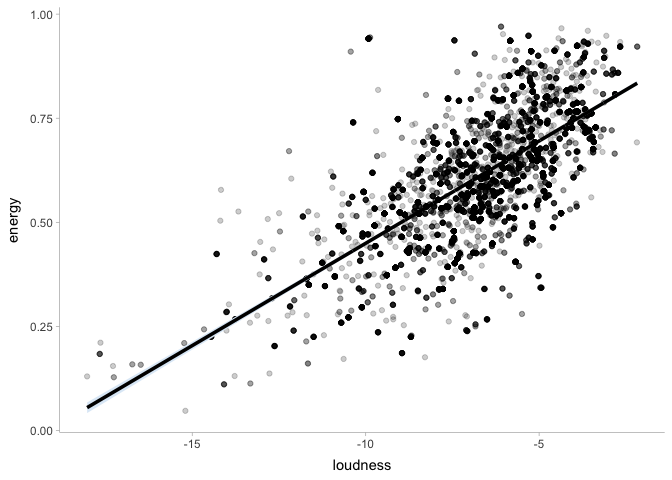

Linear Regression in Stan

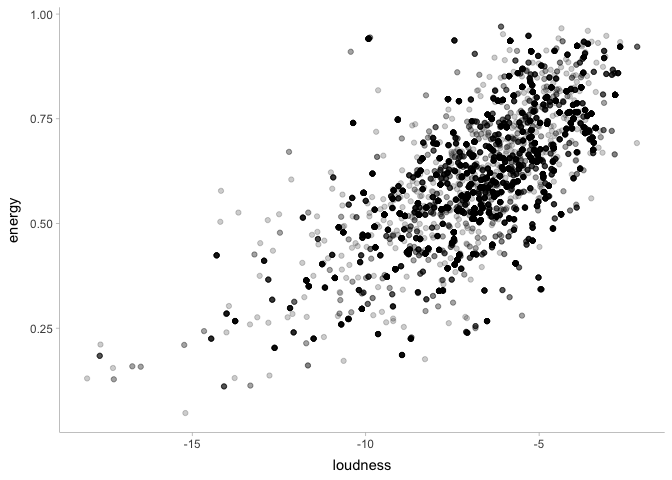

Modeling the mean and standard deviation of just one datapoint is good and well, but as scientists we’re usually more interested in effects. To do that, we’re going to need to add some predictor variables to our model. To switch things up, let’s say we want to predict the energy level of a song given the song’s loudness. First, let’s take a look at the data:

1

2

3

ggplot(spotify2021, aes(x=loudness, y=energy)) +

geom_point(alpha=.2) +

theme_tidybayes()

This certainly looks promising! Let’s write a Stan program to see if this is the case:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

data {

int<lower=0> N; // the number of data points

vector[N] x; // the loudness of each song

vector<lower=0, upper=1>[N] y; // the energy level of each song

}

parameters {

real alpha;

real beta;

real<lower=0> sigma;

}

transformed parameters {

vector[N] mu = alpha + beta*x;

}

model {

alpha ~ normal(.5, .5);

beta ~ normal(0, .1);

sigma ~ normal(0, 1);

y ~ normal(mu, sigma);

}

generated quantities {

real y_hat[N] = normal_rng(mu, sigma);

}

Hopefully by now most of this new model looks familiar: we’re modeling

energy as normally distributed with mean mu and standard deviation

sigma. However, now instead of estimating a single mu, we’re

calculating mu as a transformed parameter based on three things.

Unsurprisingly, x is the vector of loudness values for each track.

alpha is the intercept, which represents the mean energy level when

loudness == 0. And finally, beta is the slope, which represents the

average change in energy for every decible increase in loudness. The

reason we declare mu as a transformed parameter instead of a regular

old parameter is that it makes sampling more efficient: by doing so,

we’re telling Stan that mu is just some combination of the other

parameters, so we don’t need to sample it directly (we can just sample

alpha and beta). I’ve assigned normal priors for each parameter based on

sheer intuition: hopefully none of the results should vary if these are

set slightly differently.

The last thing to note is that now we’re estimating a unique y_hat for

each individual data point. The reasoning behind this is that each data

point now has a unique prediction of energy (before, the estimates did

not depend on predictors).

1

2

3

4

energy_data <- list(N=nrow(spotify2021), x=spotify2021$loudness, y=spotify2021$energy)

energy_model <- cmdstan_model('2021-12-10-energy.stan') ## compile the model

energy <- energy_model$sample(data=energy_data)

energy

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

## Running MCMC with 4 chains, at most 20 in parallel...

##

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 100 / 2000 [ 5%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 100 / 2000 [ 5%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 100 / 2000 [ 5%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 100 / 2000 [ 5%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 300 / 2000 [ 15%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 300 / 2000 [ 15%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 300 / 2000 [ 15%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 300 / 2000 [ 15%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 500 / 2000 [ 25%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 500 / 2000 [ 25%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 500 / 2000 [ 25%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 700 / 2000 [ 35%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 500 / 2000 [ 25%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 700 / 2000 [ 35%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 700 / 2000 [ 35%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 900 / 2000 [ 45%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 700 / 2000 [ 35%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 900 / 2000 [ 45%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 900 / 2000 [ 45%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 900 / 2000 [ 45%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1100 / 2000 [ 55%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1100 / 2000 [ 55%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1100 / 2000 [ 55%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1100 / 2000 [ 55%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1300 / 2000 [ 65%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1300 / 2000 [ 65%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1300 / 2000 [ 65%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1300 / 2000 [ 65%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1500 / 2000 [ 75%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1500 / 2000 [ 75%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1500 / 2000 [ 75%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1500 / 2000 [ 75%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1700 / 2000 [ 85%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1700 / 2000 [ 85%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1700 / 2000 [ 85%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1900 / 2000 [ 95%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1700 / 2000 [ 85%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1900 / 2000 [ 95%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1900 / 2000 [ 95%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 finished in 16.5 seconds.

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 finished in 17.5 seconds.

## Chain 2 Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 finished in 17.7 seconds.

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1900 / 2000 [ 95%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 finished in 19.0 seconds.

##

## All 4 chains finished successfully.

## Mean chain execution time: 17.7 seconds.

## Total execution time: 19.1 seconds.

## variable mean median sd mad q5 q95 rhat ess_bulk ess_tail

## lp__ 15649.15 15649.50 1.20 1.04 15646.70 15650.50 1.00 1272 1456

## alpha 0.94 0.94 0.00 0.00 0.93 0.95 1.00 1541 1279

## beta 0.05 0.05 0.00 0.00 0.05 0.05 1.00 1615 1370

## sigma 0.11 0.11 0.00 0.00 0.11 0.12 1.00 1672 1556

## mu[1] 0.53 0.53 0.00 0.00 0.53 0.53 1.00 3470 2550

## mu[2] 0.55 0.55 0.00 0.00 0.54 0.55 1.00 3798 2745

## mu[3] 0.62 0.62 0.00 0.00 0.62 0.62 1.00 3817 2854

## mu[4] 0.77 0.77 0.00 0.00 0.76 0.77 1.00 1671 1721

## mu[5] 0.64 0.64 0.00 0.00 0.64 0.64 1.00 3293 2835

## mu[6] 0.45 0.45 0.00 0.00 0.44 0.45 1.00 2417 2182

##

## # showing 10 of 18804 rows (change via 'max_rows' argument or 'cmdstanr_max_rows' option)

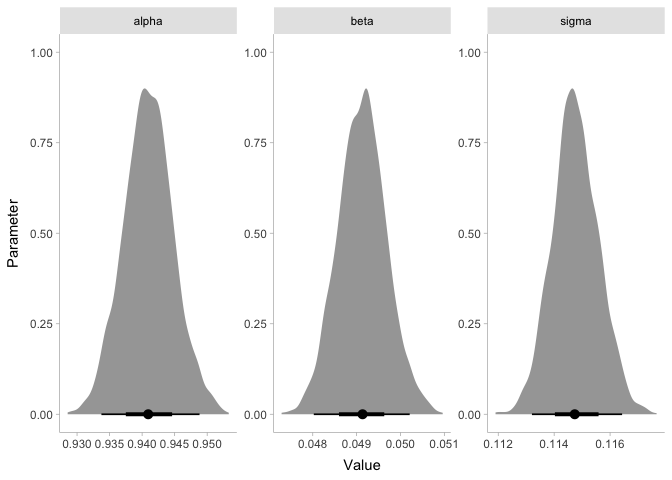

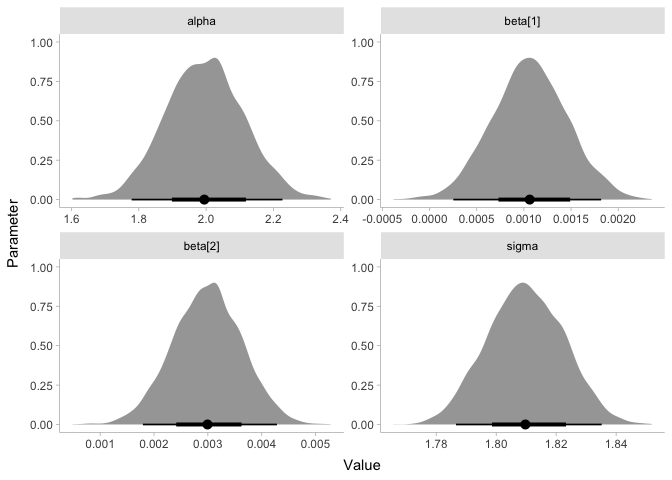

The results show that there does appear to be a sizable increase in energy with loudness! Let’s plot the coefficients to make this more clear:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

energy %>%

gather_draws(alpha, beta, sigma) %>%

ggplot(aes(x=.value)) +

stat_halfeye(point_interval=median_hdi, normalize='panels') +

xlab('Value') + ylab('Parameter') +

facet_wrap(~ .variable, scales='free') +

theme_tidybayes()

Since the coefficient beta is clearly greater than zero, we can say we

found an effect! If you’re skeptical, it might help to know that the

frequentist parameter values are extremely similar:

1

summary(lm(energy ~ loudness, spotify2021))

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = energy ~ loudness, data = spotify2021)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -0.39105 -0.06769 -0.00484 0.07276 0.48819

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 0.9410411 0.0038950 241.60 <2e-16 ***

## loudness 0.0491423 0.0005569 88.23 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.1147 on 9398 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.4531, Adjusted R-squared: 0.453

## F-statistic: 7785 on 1 and 9398 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

Let’s plot our regression line on top of the data:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

energy_draws <- energy %>%

spread_draws(mu[.row]) %>%

mutate(x=spotify2021$loudness[.row])

ggplot(spotify2021, aes(x=loudness, y=energy)) +

geom_point(alpha=.2) +

stat_lineribbon(aes(x=x, y=mu), data=energy_draws,

.width=.95, show.legend=FALSE) +

scale_fill_brewer() +

theme_tidybayes()

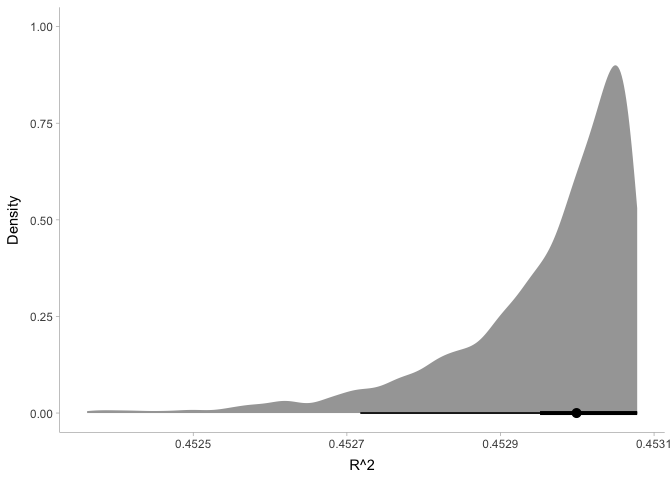

If needed, we can also use the posterior distribution to compute other

quantities of interest. For example, let’s calculate the coefficient of

variation, R^2:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

energy_R2 <- energy %>%

spread_draws(mu[.row]) %>%

left_join(tibble(.row=1:nrow(spotify2021), y=spotify2021$energy)) %>%

group_by(.draw) %>%

summarize(ss_total=sum((y-mean(y))^2),

ss_residual=sum((y-mu)^2),

R2=1 - ss_residual/ss_total)

ggplot(energy_R2, aes(x=R2)) +

stat_halfeye(point_interval=median_hdi) +

xlab('R^2') + ylab('Density') +

theme_tidybayes()

This plot shows us that our model is pretty darn good: it explains about 45% of the variance in energy!

Entering the matrix

To round off this tutorial, let’s try to make our regression model a little more general. Right now, we only have one predictor variable coded into our model. What if we wanted to allow for more than one variable and interactions between variables? As we talked about in Pranjal’s fantastic tutorial on linear algebra, the way to achieve this is to use matrices. This might sound scary, but really the core idea is still the same.

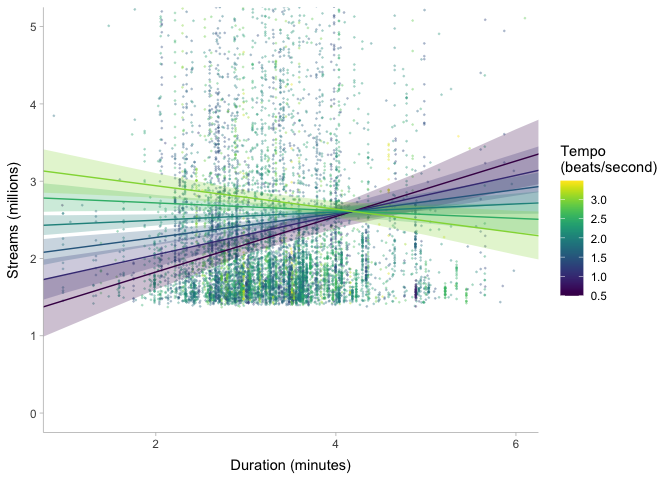

Let’s go back to stream counts: presume that we want to know what makes the top 200 songs so successful. Is it their energy, their danceability, duration, or some combination of variables? To find out, let’s code a Stan model. To keep things simple, I’m going to ignore the skew in the data and fit a model with a normal likelihood.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

data {

int<lower=0> N; // the number of data points

int<lower=0> K; // the number of regression coefficients

matrix[N, K] X; // the predictor variables

vector[N] y; // the outcome variable

}

parameters {

real alpha;

vector[K] beta;

real<lower=0> sigma;

}

transformed parameters {

vector[N] mu = alpha + X*beta;

}

model {

alpha ~ normal(0, 1);

beta ~ normal(0, 1);

sigma ~ normal(0, 1);

y ~ normal(mu, sigma);

}

generated quantities {

real y_hat[N] = normal_rng(mu, sigma);

}

As promised, there are only a few differences between this model and the

last. The most obvious difference is that while x used to be an

N-vector with one value for each data point, X is now an N by K

matrix with one row of K predictors for each data point. To make this

clear, I changed from little x to big X in the code. The other main

difference is that before we used to have a single scalar beta, which

represented the effect of x on y. But now that we have K different

x’s, beta is now a K-vector, where each element represents the

effect of the Kth predictor variable on y. What’s nice about Stan is

that everything else works just as before! Stan recognizes that beta*X

is now a vector-matrix multiplication, and it can perform the whole

multiplication out with the same code. If you think it’s more clear, you

always have the option of writing out some loops for this

multiplication:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

transformed parameters {

vector[N] mu;

// loop over data points

for (i in 1:N) {

mu[i] = alpha;

// loop over predictor variables

for (k in 1:K) {

mu[i] = mu[i] + beta[k]*X[n,k];

}

}

}

While the other version of the code was a single line, this version is 7 lines of code! And the worse part is that even though this code is longer, it’s actually slower to execute, since Stan can internally optimize matrix multiplication but it can’t internally optimize these sorts of loops. So unless you need to expand out the multiplication, it’s generally better to use the shorter version.

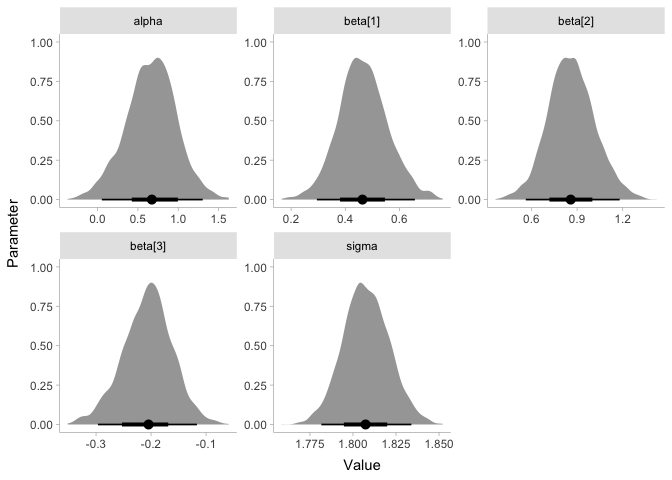

Now that we have our model, let’s try to predict stream counts using duration and tempo:

1

2

3

4

5

6

streams_data <- list(N=nrow(spotify2021), K=2,

X=select(spotify2021, duration_ms, tempo),

y=spotify2021$streams)

streams_model <- cmdstan_model('2021-12-10-streams-glm.stan') ## compile the model

streams <- streams_model$sample(data=streams_data)

streams

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

## Running MCMC with 4 chains, at most 20 in parallel...

##

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 100 / 2000 [ 5%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 300 / 2000 [ 15%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 500 / 2000 [ 25%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 100 / 2000 [ 5%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 700 / 2000 [ 35%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 900 / 2000 [ 45%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 100 / 2000 [ 5%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1100 / 2000 [ 55%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 300 / 2000 [ 15%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1300 / 2000 [ 65%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 500 / 2000 [ 25%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1500 / 2000 [ 75%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 100 / 2000 [ 5%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 700 / 2000 [ 35%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1700 / 2000 [ 85%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 1900 / 2000 [ 95%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 900 / 2000 [ 45%] (Warmup)

## Chain 1 Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 1 finished in 10.3 seconds.

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1100 / 2000 [ 55%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 300 / 2000 [ 15%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1300 / 2000 [ 65%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1500 / 2000 [ 75%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1700 / 2000 [ 85%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 1900 / 2000 [ 95%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 3 finished in 24.6 seconds.

## Chain 4 Iteration: 300 / 2000 [ 15%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 500 / 2000 [ 25%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 500 / 2000 [ 25%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 700 / 2000 [ 35%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 700 / 2000 [ 35%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 900 / 2000 [ 45%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 900 / 2000 [ 45%] (Warmup)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1100 / 2000 [ 55%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1100 / 2000 [ 55%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1300 / 2000 [ 65%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1500 / 2000 [ 75%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1700 / 2000 [ 85%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 1900 / 2000 [ 95%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 2 finished in 119.5 seconds.

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1300 / 2000 [ 65%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1500 / 2000 [ 75%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1700 / 2000 [ 85%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 1900 / 2000 [ 95%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

## Chain 4 finished in 247.5 seconds.

##

## All 4 chains finished successfully.

## Mean chain execution time: 100.5 seconds.

## Total execution time: 247.6 seconds.

## variable mean median sd mad q5 q95

## lp__ -5158838.53 -152326.00 8680417.44 210440.84 -20199705.00 -10386.00

## alpha 0.36 0.48 1.21 1.19 -1.45 1.93

## beta[1] 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

## beta[2] 0.20 0.01 0.51 0.17 -0.28 1.06

## sigma 1.79 1.50 1.09 0.91 0.65 3.32

## mu[1] -5.03 2.84 20.73 7.29 -40.00 14.76

## mu[2] 3.39 2.46 2.45 0.98 1.01 7.51

## mu[3] 4.02 2.35 4.42 1.72 -0.27 11.45

## mu[4] 3.73 2.13 4.42 1.91 -0.66 11.14

## mu[5] 7.77 2.66 13.40 4.58 -4.93 30.41

## rhat ess_bulk ess_tail

## 3.57 4 11

## 3.55 4 8

## 4.08 4 10

## 4.23 4 11

## 4.29 4 11

## 4.05 4 10

## 3.59 4 10

## 3.87 4 10

## 3.96 4 10

## 3.36 4 10

##

## # showing 10 of 18805 rows (change via 'max_rows' argument or 'cmdstanr_max_rows' option)

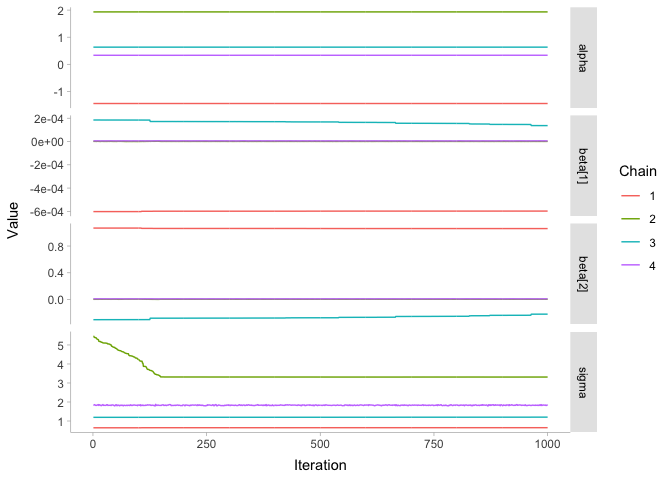

Oh, that doesn’t look good… what went wrong? In addition to taking really long to fit, we get some scary warnings, and the R-hat values are huge! Let’s look at the chains:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

streams$draws(c('alpha', 'beta', 'sigma'), format='draws_df') %>%

pivot_longer(alpha:sigma, names_to='.variable', values_to='.value') %>%

ggplot(aes(x=.iteration, y=.value, color=factor(.chain))) +

geom_line() + xlab('Iteration') + ylab('Value') +

scale_color_discrete(name='Chain') +

facet_grid(.variable ~ ., scales='free_y') +

theme_tidybayes()

These are some bad looking chains! To get an idea of what went wrong, let’s take another quick look at our data:

1

summary(streams_data$X)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

## duration_ms tempo

## Min. : 52062 Min. : 40.32

## 1st Qu.:167916 1st Qu.: 97.69

## Median :195873 Median :121.97

## Mean :198911 Mean :121.97

## 3rd Qu.:221980 3rd Qu.:142.59

## Max. :690732 Max. :208.92

One thing stands out to me: the scale of duration_ms is much much

larger than that of tempo and loudness. This can actually cause

problems in prior specification and model fitting, because Stan doesn’t

know that since duration_ms is much larger, its beta weights should